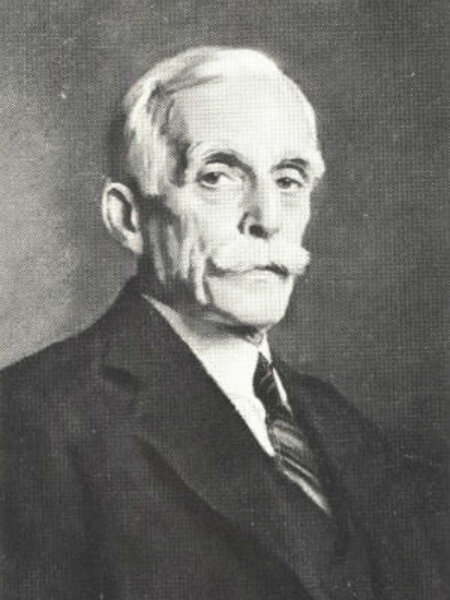

There's no evidence that President Coolidge personally directed the IRS to punish political enemies. But his Treasury secretary – banker and industrialist Andrew Mellon – had no such scruples. Secretary Mellon's target was Sen. James Couzens (R) of Michigan, a former general manager of the Ford Motor Co. and a fellow millionaire who launched a congressional probe of tax rebates given to Mellon companies during World War I. The investigation revealed that Mellon had misrepresented the extent to which he was still involved in the management of his own companies, such as Alcoa, prompting calls for his resignation on the eve of the 1924 presidential vote.

After Coolidge was reelected, the Treasury under Mellon reopened the senator's 1919 tax return and ordered Couzens to pay $11 million in back taxes. But that wasn't the end of it. An appeals board eventually reversed that outcome and concluded that, in fact, Couzens was entitled to a refund. "This decision was the greatest humiliation Mellon had yet suffered at the Treasury," wrote biographer David Cannadine.

However, the incident set a template for future administrations for using the tax code to attack political opponents – a weapon that would be turned against Mellon himself in the Roosevelt administration.