Trump officials say the president might suspend habeas corpus. Can he do that?

Loading...

In the past two weeks, two White House officials have floated the idea that President Donald Trump could suspend habeas corpus. Enshrined in the U.S. Constitution to protect people from being unlawfully detained, habeas claims have emerged as an effective obstacle to the Trump administration’s efforts to deport large numbers of immigrants from the country.

The Constitution says habeas corpus can be suspended in specific situations, and White House officials argue that the recent influx of illegal immigration constitutes an invasion that allows for the suspension of habeas rights.

Habeas corpus has been suspended four times in U.S. history, and always with some kind of approval from Congress – one time, after the fact. Habeas rights have been suspended in specific locations, but never, legal experts say, for specific groups of people, such as unauthorized immigrants.

Why We Wrote This

The U.S. Constitution allows habeas corpus to be suspended in situations such as an invasion – and the Trump administration suggests the influx of illegal immigration meets that description. The writ has been suspended four times in U.S. history.

What is habeas corpus?

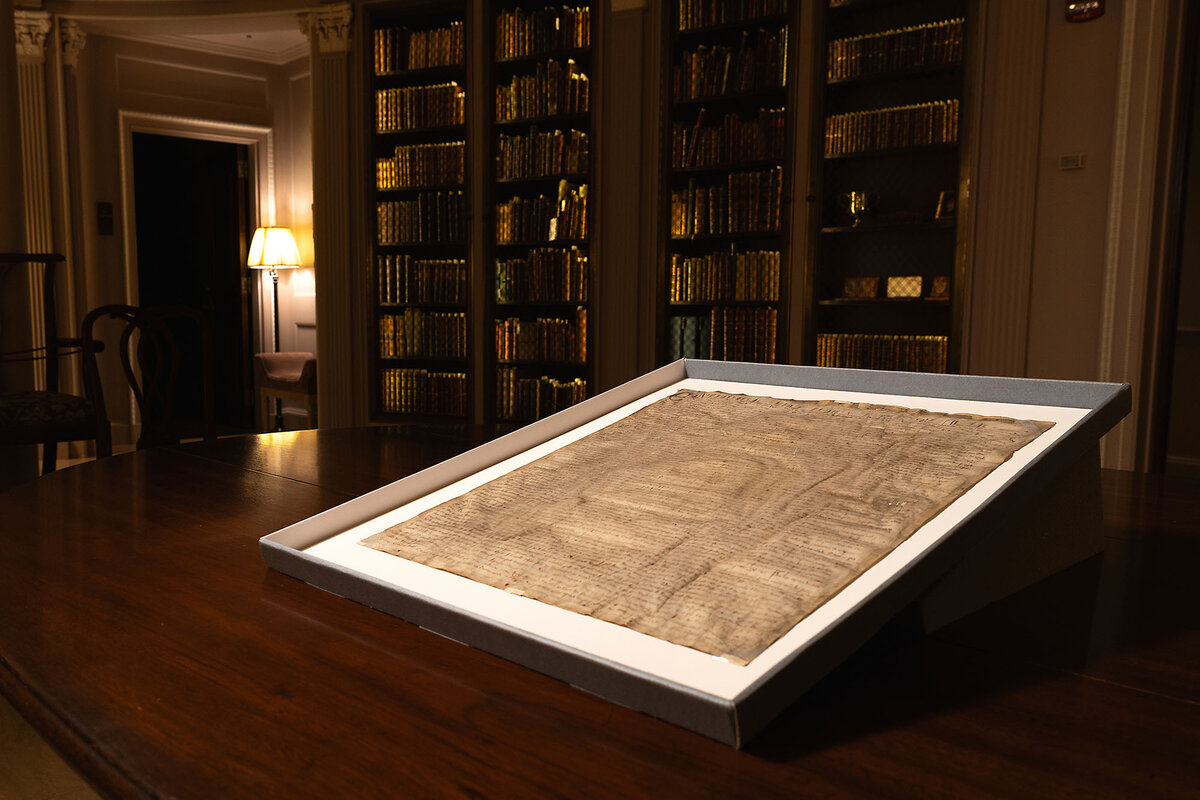

Habeas corpus can be traced to before the Magna Carta. Sometimes referred to as the “great writ of liberty,” habeas is a legal procedure that allows an individual to argue before a court that their detention is illegal. U.S. courts have interpreted this right as extending to noncitizens, such as men detained at Guantanamo Bay.

The U.S. Constitution includes various protections for individual liberty. The due process clause of the 14th Amendment says no person can be deprived “of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law.” The Fifth Amendment gives people a right not to self-incriminate, or be tried for the same crime twice. The Sixth Amendment provides a right to a speedy trial, and the Eighth Amendment forbids excessive bail – both protections against extended incarceration.

Habeas corpus is older than all of these rights. Having been included in the Magna Carta in 1215, and later codified by the British Parliament in 1679, the Framers adopted habeas as a foundational American right. Habeas corpus, the Constitution says, “shall not be suspended, unless when in cases of rebellion or invasion.” Exactly when, and how, habeas can be suspended is unclear, but scholars say some clear rules have emerged over time.

“Members of the founding generation referred to habeas as ‘essential to freedom,’” says Amanda Tyler, a professor at the University of California, Berkeley, School of Law.

As such, she adds, they expected habeas to be suspended “only in the most dramatic of circumstances.”

When has habeas corpus been suspended in the U.S.?

The most referenced example is President Abraham Lincoln’s suspension of habeas corpus during the Civil War. Roger Taney, the chief justice of the U.S. Supreme Court, ruled days later that only Congress could suspend habeas corpus. President Lincoln ignored this ruling, and two years later Congress retroactively approved his suspension of the writ.

Congress voted to suspend habeas corpus in parts of South Carolina a decade later in response to Ku Klux Klan violence and intimidation during Reconstruction. In 1905 U.S. officials suspended habeas corpus in parts of the Philippines, then a U.S. territory, amid worries about an insurrection. After the attack on Pearl Harbor, the governor of Hawaii, which was also a U.S. territory at the time, suspended habeas corpus.

Neither Congress nor President George W. Bush suspended habeas corpus following the 9/11 terrorist attacks, though Congress did pass legislation giving the executive branch broader powers to surveil Americans.

“At least in the initial days and weeks after the attacks, that was much closer to a genuine emergency than what you have now with immigration,” says Gerard Magliocca, a professor at Indiana University’s Robert H. McKinney School of Law.

What has the Trump administration been saying?

Secretary of Homeland Security Kristi Noem has addressed habeas corpus twice recently. Last week, she told a U.S. House committee that illegal immigration levels could warrant suspending the right. Appearing before a U.S. Senate committee this week, she erroneously described habeas corpus as “a constitutional right that the president has to be able to remove people from this country.”

“That’s incorrect,” replied Democratic Sen. Maggie Hassan of New Hampshire. “Habeas corpus is the foundational right that separates free societies like America from police states like North Korea.”

Last week, Trump adviser Stephen Miller said the administration is “actively looking at” suspending habeas corpus as a means of addressing illegal immigration. Because of laws passed by Congress, he reasoned, independent federal courts “aren’t even allowed to be involved in immigration cases.”

What does the law say about that?

Mr. Miller said, correctly, that the Constitution “is clear” that habeas corpus can be suspended “in a time of invasion.” It’s also true that unauthorized immigrants are entitled to less due process in certain situations, such as how recently they entered the country. Immigration courts, which are separate from federal courts, also have the final say on whether an immigrant can stay in the country or if they must leave.

But immigrants facing deportation can raise certain arguments against their removal in federal courts. Indeed, in litigation concerning the Alien Enemies Act – a law that allows a president to remove nationals of a country engaged in a war, invasion, or predatory incursion of the U.S. – the U.S. Supreme Court has ruled that challenges to removal under the Act “must be brought in habeas.” Several federal courts have since paused deportations, saying the U.S. is not currently under invasion. (A federal judge this week did defer to the administration’s claim that a “predatory incursion” is underway.)

In another set of cases, the government revoked residency documents for, and has been trying to deport, international students who have voiced opposition to Israel’s war in Gaza, after the secretary of state said their continued presence “would have potentially serious adverse foreign policy consequences” for the U.S. A federal judge in Vermont rejected the argument that one of those students couldn’t raise a habeas claim.

The student “has raised a substantial claim that the government arrested him to stifle speech with which it disagrees,” wrote Judge Geoffrey Crawford. “Such an act would violate the Constitution – quite separate from the removal procedures followed by the immigration courts.”

Whether the Trump administration will try to suspend habeas corpus remains unclear.