More immigrants face deportation: What due process are they owed?

Loading...

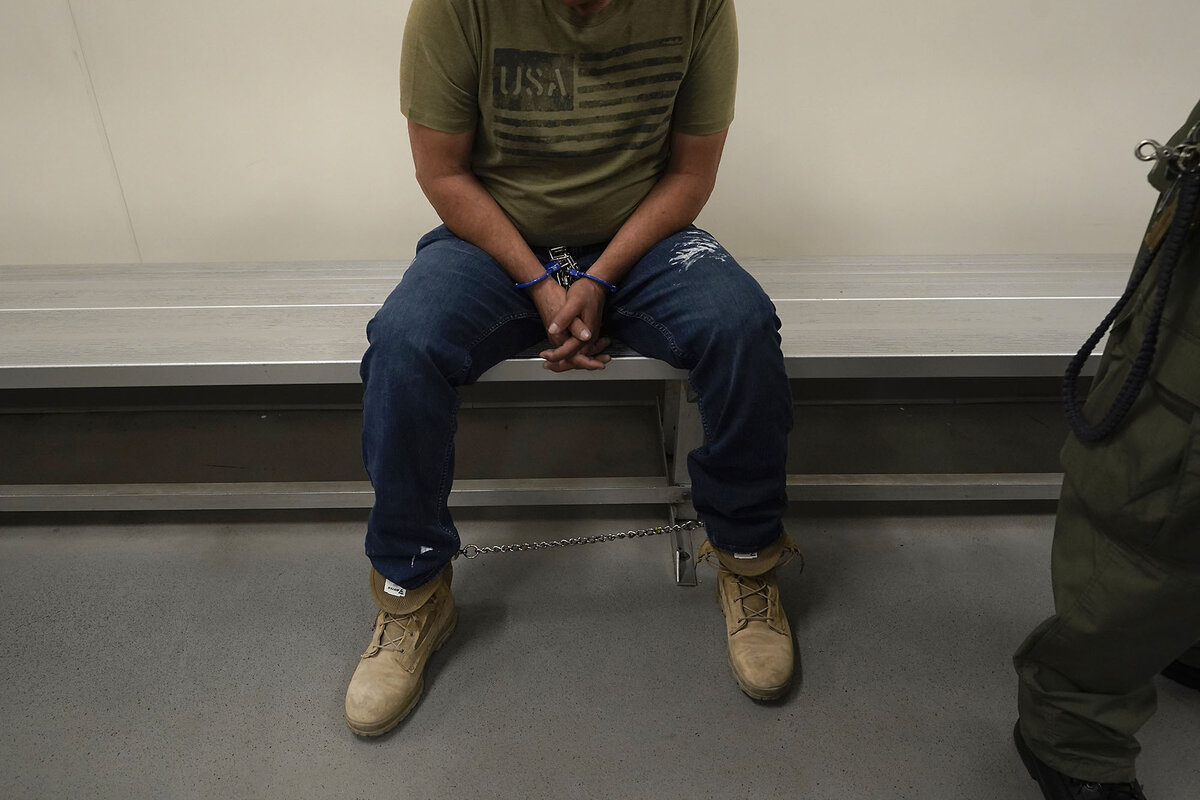

As the Trump administration claims broad authority to summarily deport “alien enemies” in an “invasion,” efforts to control U.S. borders and immigration are running up against concerns for individual rights.

For immigrants, one of the most basic rights – the ability to have due process in a court of law – is in question.

The tension isn’t entirely new. Due process for immigrants has been litigated over for more than a century, says Nicole Hallett, director of the Immigrants’ Rights Clinic at the University of Chicago Law School. But the Trump administration is using executive powers “in a new and unprecedented way.” Courts may ultimately decide where the line around protections gets drawn.

Why We Wrote This

Immigrants may not have the same status as citizens, but they do have legal rights in the United States. Boundaries are being tested as the Trump administration claims broad authority to deport “alien enemies” and others.

“If you give one branch of government an extraordinary amount of power over a group of people, which is what we’ve done with noncitizens in the United States, we are relying on that branch of government to use that power judiciously,” Professor Hallett says. Meanwhile, the current White House “intends to stretch their power to the absolute limit.”

What does due process mean?

Legal experts say due process boils down to providing notice of accusations and giving people the opportunity to be heard in their own defense. The Constitution’s 14th Amendment guards against depriving “any person of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law.”

Just as in the Fifth Amendment, lawyers note the use of “person” – not citizen.

“Everyone has the right to the kind of basic procedural protections when the government is trying to take something away from you,” says Professor Hallett. That said, the level of protection “might vary depending on your [immigration] status.”

So are immigrants entitled to due process?

Yes. In the realm of immigration enforcement, though, the process to which they are entitled is generally dictated by Congress.

In criminal matters, noncitizens are afforded the same due process protections as citizens. Relatedly, they have a right to be protected from self-incrimination. Criminal defendants, no matter their immigration status, are also entitled to free counsel.

Immigrants don’t need to be convicted of a crime to be deported, though. Immigration courts, which decide whether people can stay or must leave, are separate from the federal court system. As immigration judges don’t hear criminal cases, noncitizens in that system are not entitled to free counsel. That has led, at times, to children representing themselves.

Defense of immigrants’ due process rights has transcended ideological lines. Late Supreme Court Justice Antonin Scalia, a conservative, wrote in a 1993 opinion: “It is well established that the Fifth Amendment entitles aliens to due process of law in deportation proceedings.”

Location adds a layer of complexity. Constitutional rights don’t always fully apply at U.S. borders, including ports of entry like airports. Anyone, including U.S. citizens, can be searched in those places in ways that may not be deemed legal elsewhere, under the Fourth Amendment.

Different immigration pathways also have their own protocols. The State Department can revoke visas – as it currently is doing for certain foreign students tied to campus protests. Generally, it’s up to an immigration judge to decide whether a green card holder’s lawful permanent resident status should be taken away. But again, there may be exceptions, such as if the government, within the first five years, concludes the green card was issued in error.

How is immigrant access to due process being challenged now?

The most prominent case involves the president’s reliance on a rarely used wartime authority to deport immigrants whom the government accuses of being terrorists.

In a proclamation signed last month, President Donald Trump invoked the Alien Enemies Act of 1798 to direct the detention and removal of suspected members of Tren de Aragua, a Venezuelan gang the government has called a foreign terrorist organization. (The president has said he “didn’t sign” the proclamation, despite his signature reflected in the Federal Register.)

The government began deporting immigrants to El Salvador under that authority last month; a federal appeals court has since upheld a temporary restraining order that bars deportations under the act. The government has asked the Supreme Court to intervene.

The American Civil Liberties Union and Democracy Forward, which are suing the government, say it whisked hundreds of people onto planes to El Salvador “without providing advance notice, let alone an opportunity to contest their deportation.” The proclamation also does not provide any process for immigrants to rebut claims of being gang members, they note in a court filing.

The Trump administration and its allies offer a different position. White House adviser Stephen Miller wrote on the social platform X Tuesday: “If you illegally invaded our country the only ‘process’ you are entitled to is deportation.”

America First Legal, which Mr. Miller helped found, elaborated on this argument. It underscored the president’s authority under the Alien Enemies Act and drew a parallel to the government’s rapid expulsion of border crossers during the pandemic.

“‘Due process’ arguments are irrelevant,” the group said in a post.

Immigrant advocates and liberals have expressed outrage, especially as new accounts have emerged disputing suspected gang ties of some of the men sent to El Salvador. For the government to claim that people are not entitled to any due process “violates the basic principle of what this country was founded on,” says Aaron Reichlin-Melnick, senior fellow at the American Immigration Council.

But former immigration judge Andrew Arthur says it’s “an open question” how much process is due to noncitizens in removal cases under the Alien Enemies Act. And looking at “the way that Congress wrote the provision, it’s likely not much,” Judge Arthur, a resident fellow at the Center for Immigration Studies, adds in an email.

As the president checks off campaign promises, polls indicate that his base broadly approves of his border-security and deportation efforts. Still, some proponents of restricted immigration have raised concerns over tactics and the wartime authority’s use.

Mark Krikorian, a longtime advocate of immigration restrictions and executive director of the Center for Immigration Studies, says he’s not opposed to the “novel way” the Trump administration is invoking wartime powers, as “war has changed.”

Still, “People do have a right to go to court and say ‘I’m not a Tren de Aragua member, and therefore this [proclamation] doesn’t apply to me,’” says Mr. Krikorian. After all, “What if an American citizen got picked up?”

The government has admitted at least one mistake so far.

In a court filing, Justice Department lawyers said the administration deported a Salvadoran man living in Maryland to El Salvador last month because of an “administrative error,” the Atlantic reported. An immigration judge had previously granted the man a legal protection against deportation. Details are still emerging, but the government claims that the federal court now lacks jurisdiction over the matter because the man is no longer in U.S. custody.

What is expedited removal?

Expedited removal is a fast-track deportation option the government can use.

Immigration lawyers generally see it as an exception, created by Congress, to immigrants’ typical access to due process. That’s because expedited removal allows for an immigrant to be deported without access to an immigration judge, unless they speak up about wanting to seek asylum.

This rapid deportation option became part of U.S. immigration law in 1996 under President Bill Clinton. The provision, since its start, has allowed for the expedited removal of immigrants in the U.S. within two years of their arrival. In practice, however, it has typically been enforced along the borders, including for unauthorized immigrants apprehended within two weeks of their arrival.

Mr. Trump has signaled an expansion of enforcement. A notice published Jan. 24 in the Federal Register by the Department of Homeland Security says it is restoring “the scope of expedited removal to the fullest extent authorized by Congress” as a way to “enhance national security and public safety.”

So far, it’s unclear if there has been an increase in authorities using expedited removal, in part because the government hasn’t published monthly enforcement statistics since the inauguration.

Yet as the Trump administration revokes legal protections for hundreds of thousands of immigrants previously granted temporary permission to live and work in the U.S., lawyers say those people could be exposed to expedited removal. And that could mean no immigration court hearing.

“It’s not intended as the general method of removal of people in the United States,” says Deep Gulasekaram, immigration and constitutional law professor at the University of Colorado Boulder. But “The more you expand it, the more it becomes the default regime.”