What it’s actually like to be a poll worker in the 2024 US election

Loading...

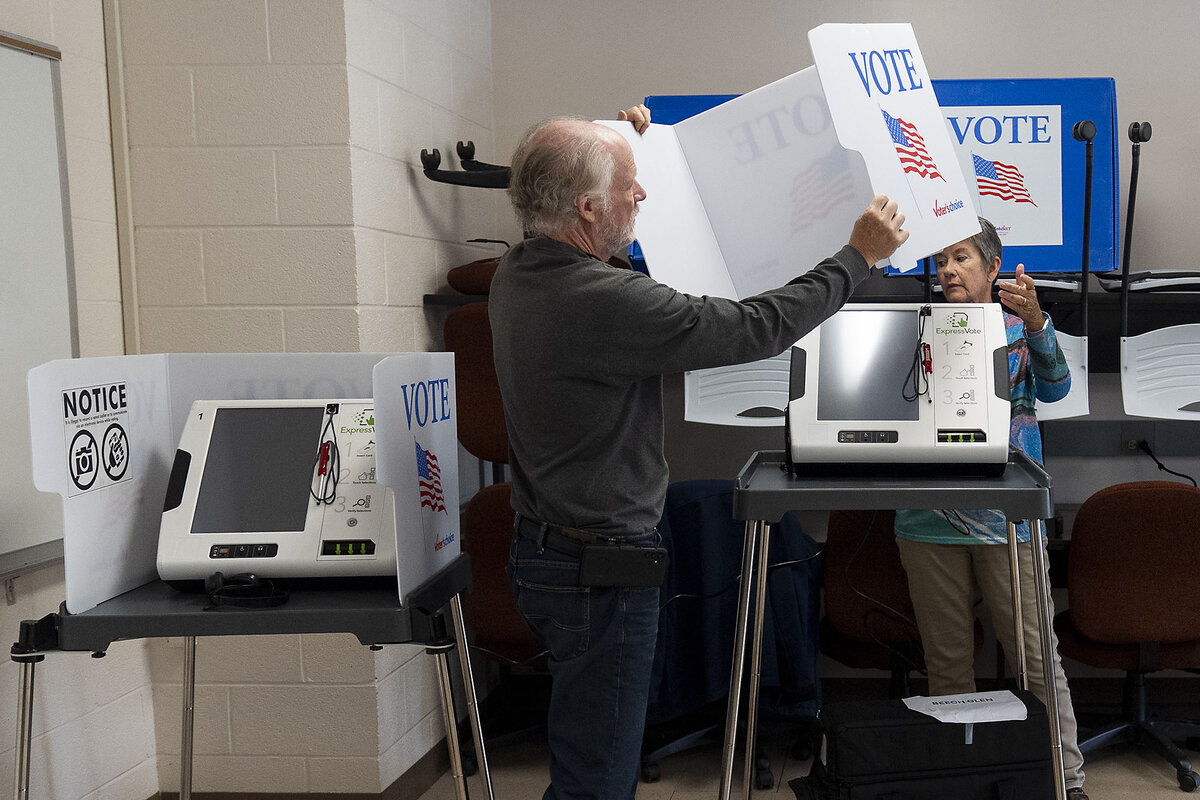

| Media, PA.

When voters head to the polls next week, the millions of ballots cast will be processed by at least 700,000 election workers across the United States. Most of those involved are either volunteers or temporary staff who are paid modestly, some as little as $5 per day, to set up equipment, verify voter registration and identification, and count ballots.

Amid misinformation about election integrity, threats aimed at election workers spiked in 2020 and have remained high since. In response, election officials around the country from both major parties have worked to educate voters about how elections work, saying the more people understand the process, the more they trust the results.

The specifics of poll workers’ jobs vary by locality since most election administration is conducted at the county level. But generally speaking, these positions around the country follow a similar model.

Why We Wrote This

Election workers play a key role in running voting operations on Election Day. Their role has come under increased scrutiny since the 2020 U.S. elections. Here’s what this position involves – and how people are handling the pressure.

You don’t work for political parties

Election workers are unaffiliated with political parties. Often, they serve in the community where they live. Poll workers are different from poll watchers who volunteer – typically with a party or partisan group – to observe how elections are carried out.

Most states require poll workers to be a U.S. citizen, above 18, and without a criminal background that would prevent them from voting.

Poll workers aren’t typically allowed to discuss politics while they’re on the job, or even wear clothing that expresses political opinions. “Up until 6 a.m. on Election Day, you can have your opinions,” an instructor told a room of about 40 poll workers during a training this month in Media, Pennsylvania, a small town outside of Philadelphia.

Ishea Jennings, an attendee at the training, signed up to be a poll worker two years ago in part because she didn’t see many other minorities who were doing that work.

She was the the only millennial working at her polling place in the 2022 midterm elections, but for Pennsylvania's 2024 primaries, she was impressed to see high schoolers who weren’t old enough to vote spending their day working at the polling place.

“I always thought that these were, like, state government employees that were doing this,” Ms. Jennings says, “so just knowing that these are average people that are running it is really cool.”

You complete hours of training

Almost all states require training for at least some poll workers. In the states that don’t, some counties develop their own training course.

In Media, Pennsylvania, that training consists of three hours on a Monday evening in a county government office, where poll workers are walked through how to use the equipment and learn what they’ll be responsible for in the polling place. They're also given a 100-page election guide that walks them through a slew of scenarios they might have to deal with on Election Day. It includes numbers to call for support, from a poll worker’s hotline if there’s a technology failure, to the District Attorney’s office if someone tries to block voters from entering the polling place.

It’s similar in Montgomery County, Maryland. Eamon Vahidi, who’s worked elections in California and then Maryland since 2016, went through an online training and quiz, followed by a three-hour, in-person training in order to work the polls this year.

In Maricopa County, Arizona, the poll worker training manual includes instructions on how to reach a hotline in situations such as voter wait times surpassing 30 minutes or power outages at the polling facility.

You have to think on your feet

Handling equipment and checking voters in is only part of a poll worker’s job. They’re also tasked with making sure voters can exercise their right to vote without interference.

That means being observant. If a voter might need assistance to fill out a ballot, it’s their job to notice that. If poll watchers are getting in voters’ way, they’ll need to step in.

Often, in the polling place where Mr. Vahidi works, voters don’t realize they are not allowed to have cellphones out, he says. At his site, one worker is assigned to the door to watch for phones and offer voters pencil and paper to copy down their voting plan, which many bring on their phone.

When Ms. Jennings worked the polls in Pennsylvania for the first time, she made an emergency trip to the Dollar Tree. Her precinct served a lot of senior citizens, and she and her co-workers realized that some were struggling to read their ballots. They bought extra eyeglasses, which they handed out to voters who needed them.

Melissa Harris, a Georgian who will be working the polls in her third election next week, often has to help voters who come to the wrong precinct.

You’re not a poll watcher

Poll workers facilitate elections. Poll watchers observe them. And, unlike poll workers, poll watchers are often recruited by a party or partisan organization. They’re dispatched to polling places and election headquarters, where they observe the casting and counting of ballots, flag any suspected irregularities they see, and often provide on-the-ground reports about turnout to their party.

As with election workers, the rules governing poll watchers vary by state. In most cases, they’re not supposed to interfere in any way or speak with voters in the polling place. Often, they have to stand a certain distance away from voting machines.

Wenda Kincaid, an election judge in Berks County, Pennsylvania, has noticed a big uptick in the number of poll watchers. More often than not, she says, the issues she encounters on election day are not from the general public, but from poll watchers “who aren’t trained, or aren’t following the training they’re supposed to have.”

Your job is harder this time

Threats to poll workers’ safety spiked following Mr. Trump’s unfounded claims that the 2020 election was stolen. In a May 2024 report, over a third of local officials reported experiencing threats or harassment, according to the Brennan Center for Justice. Seventy percent of local election officials reported feeling as if threats have increased since 2020, and 92% of election administrators have taken steps to increase security for election workers and voters.

“I think that given the temperature of these past elections, I have been concerned,” says Ms. Harris, the poll worker from Georgia. But the importance of her work outweighs those worries. “I just think that in order to have an active role and a democracy that we care about, everyone should consider, how can they get out and do something?”

There are indications that most of the public still trusts their local election workers. Among supporters of Vice President Kamala Harris, 97% believe poll workers in their community will do a good job, as do 84% of former President Donald Trump’s supporters, according to a recent Pew Research Center survey.

In her community, election workers are generally anxious – mostly because of the national temperature, says Ms. Kincaid, the election judge. She doesn’t expect tempers to run high in her rural county, though. “The people who are voting are our friends, our neighbors, our family. These are people we’re going to see at the grocery store.”