Two states warn that Biden may be kept off their ballots

Loading...

The Republican secretaries of state in Ohio and Alabama sent letters to local Democratic party chairs this past week with a warning: President Joe Biden, as the law stands now, won’t appear on their states’ ballots in November.

Both secretaries say the president’s nomination at the Democratic National Convention in Chicago between Aug. 19 and 22 won’t meet their states’ ballot access deadlines, which require candidates’ party certification 82 to 90 days before Election Day.

The Biden campaign has seemed relatively unfazed by the news, assuring reporters that the president will appear on the ballot in all 50 states. Its confidence may be based on recent history. Just four years ago, the Ohio legislature approved changing its deadline to 60 days before the election to accommodate Mr. Biden as well as Donald Trump, when both the Republican and Democratic conventions were held in late August. Similarly, a one-time exception for Mr. Trump passed the Alabama Legislature unanimously in 2020 (with a vote from current Secretary of State Wes Allen, who was in the Alabama House at the time).

Why We Wrote This

Election integrity relies heavily on America’s state election officials, yet these roles have grown increasingly politicized. The latest sign is tension over whether two states might leave President Joe Biden off the ballot.

But this year could prove to be more of a struggle.

Ohio’s and Alabama’s declarations have been seen by some as a partisan reaction to the effort supported by Colorado’s Democratic secretary of state to keep Mr. Trump off her state’s ballot because of his role at the Capitol on Jan. 6, 2021 – a decision that was unanimously overruled by the U.S. Supreme Court. In response, Republican lawmakers in Colorado attempted to impeach Secretary Jena Griswold for “abuse of the public trust,” but their effort failed in committee on Tuesday.

The secretary of state role has become increasingly fraught since the 2020 election, when the Trump campaign made many previously under-the-radar election officials the focus of election integrity accusations, causing some to face death threats. Now it may be harder than ever for these statewide election officials, who play a referee-type role that calls for impartiality, to be seen as operating in a nonpartisan manner.

“[Secretaries of state] are elected to oversee elections, but they are a partisan member of one party, so these types of tensions shouldn’t be surprising,” says Daniel Schnur, who teaches political communication at the University of California, Berkeley and the University of Southern California and who lost a campaign to be California’s secretary of state in 2014. “It’s never been easy for someone in a job like this one to balance those obligations, but there’s no question that it’s becoming even harder.”

Ideals of impartiality under pressure

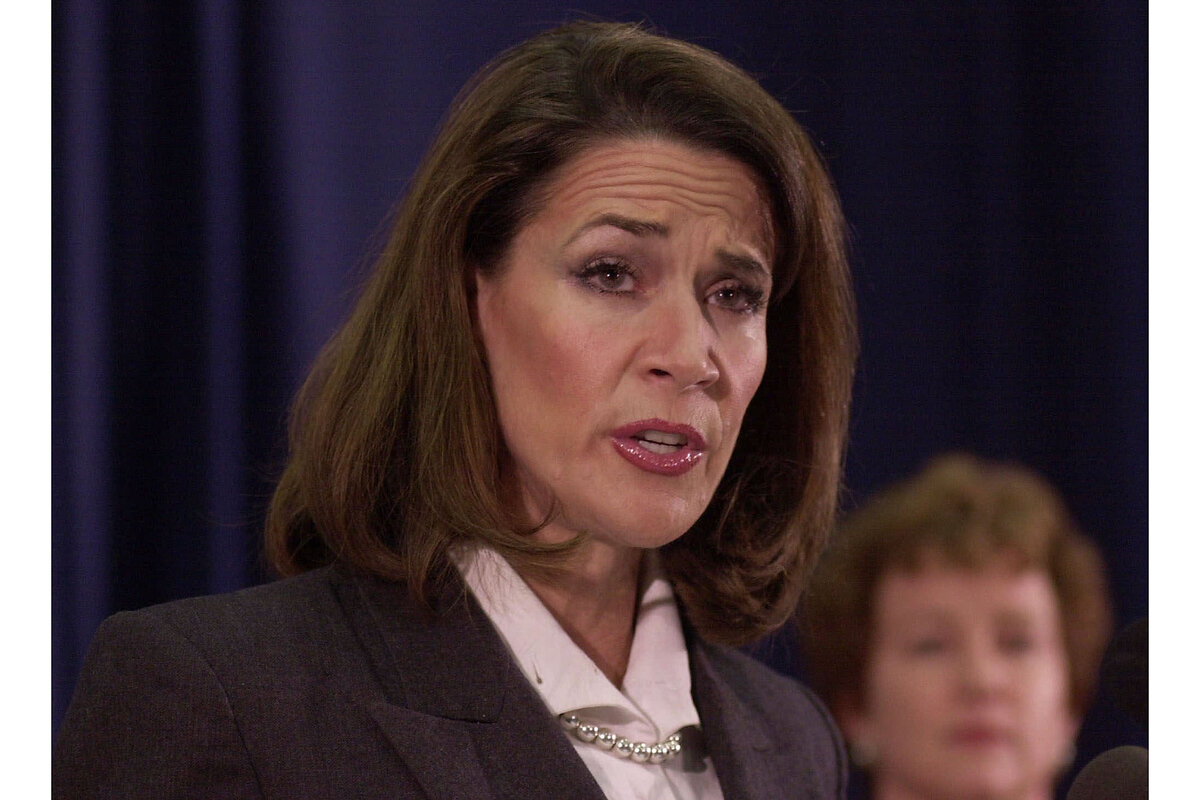

The encroachment of partisanship on secretaries of states’ duties, or accusations of it, is not a new phenomenon. In the 2000 election Katherine Harris, then-secretary of state for Florida, who had campaigned for George W. Bush, was criticized for several decisions in the state’s recount that called Florida – and the presidency – for Mr. Bush.

Dan Tokaji, dean of the University of Wisconsin Law School and an expert on election law, also cites the 2004 election in Ohio. Then-Secretary of State Ken Blackwell, a Republican and co-chair for President Bush’s reelection campaign in the state, took steps to restrict voting access in Ohio (including rejecting any voter registration form that wasn’t printed on thick card stock). Mr. Bush won the state by 2 percentage points.

“There is a conflict of interest built into this job,” says Mr. Tokaji. “But the pressures have definitely become more intense over the past four years.”

When Mr. Trump asked Georgia’s GOP Secretary of State Brad Raffensperger to “find” votes to overturn Mr. Biden’s win in a now-infamous phone call in 2021, that call “brought things up to a different level than what we had seen previously,” says Mr. Tokaji. Since then, many election officials have left their jobs out of frustration. Elections to fill those roles have taken center stage. According to a report from the Brennan Center, six secretary of state candidates in battleground states raised over $26 million in 2022, more than double the amount raised in 2018.

Will ballot access end up in court?

The intensified polarization of the position is evident in this week’s ballot access statements, says Richard Winger, founder of Ballot Access News. A few states have had to temporarily change ballot access deadlines to accommodate major-party presidential candidates in almost all recent elections, says Mr. Winger, “and they always do.” In 2020 alone, five states, including Ohio and Alabama, temporarily changed their deadlines.

“All previous times, before the secretary of state put out a press release, he or she would have also said, ‘I’m working with the legislature to fix this,’” he adds. “This year is different.”

But like the Biden campaign, Mr. Winger isn’t worried about this year making history as the first time a major party’s presidential candidate is kept off a state ballot.

If Democrats are unable to fix their Ohio and Alabama challenge through traditional means, they could choose to sue, and Mr. Winger has “no doubt” that the deadlines would fall in court. Federal courts, including the Supreme Court, have already overturned ballot deadlines several times, even for minor-party candidates.

State officials so far aren’t showing signs of compromise.

“I am left to conclude that the Democratic National Committee must either move up its nominating convention or the Ohio General Assembly must act by May 9, 2024 (90 days prior to a new law’s effective date) to create an exception to this statutory requirement,” wrote Paul DiSantis, chief legal counsel for Ohio Secretary of State Frank LaRose, in a letter last week to Ohio Democratic Party Chair Liz Walters.

On Monday, Alabama’s Secretary Allen sent a similar letter to state Democratic Party Chair Randy Kelley that was copied to Democratic National Committee Chair Jaime Harrison.

“If this Office has not received a valid certificate of nomination from the Democratic Party following its convention by the statutory deadline, I will be unable to certify the names of the Democratic Party’s candidates for President and Vice President for ballot preparation for the 2024 general election,” Mr. Allen wrote.