Trump trial: How to safeguard justice, juries, and speech?

Loading...

| Tybee Island, Ga.

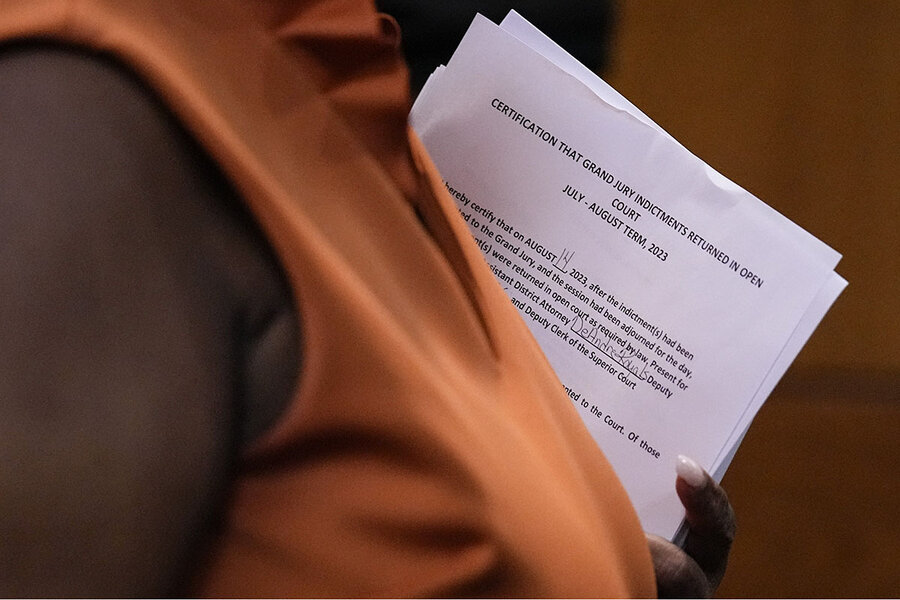

When the staff at Fulton County courthouse in Georgia published the names of the 23 grand jurors who voted to indict former President Donald Trump, many Americans were taken aback. Why would you reveal the names of grand jurors in such a sensitive case?

But in Georgia, no one was surprised. It is standard practice here to print grand jurors’ names, unredacted, on indictments. After all, the rationale goes, why should those who make serious allegations against fellow citizens be granted anonymity?

That effort toward transparency has now become a potential liability. Some of Mr. Trump’s supporters have begun circulating the jurors’ names online – along with purported addresses, pictures of homes, and in some cases, racist invectives and threats.

Why We Wrote This

A story focused onWhen the names of the grand jurors who indicted Donald Trump were made public, it sharpened an urgent question. At a time of heightened threats against the judiciary, how should the United States balance transparency and safety?

“Everyone on that jury should be hung,” one person wrote on a right-wing online forum. Another wrote, “I see a swift bullet to the head if, and when, somebody shows up at their homes.”

The Georgia grand jury teed up one of the most controversial and emotional prosecutions ever for the republic when it voted to indict the former president earlier this week – bringing the number of indictments he now faces to four. Mr. Trump has not made any overt threats against jurors, but he has repeatedly painted the process, judges, and prosecutors as corrupt. Judge Tanya Chutkan, who is presiding over his federal election interference trial in Washington, has warned him against making comments that could be seen as intimidating or threatening. This week, a woman in Texas was charged with threatening to kill Judge Chutkan.

The situation is posing a new and serious challenge: how to protect the well-being and safety of jurors, judges, and prosecutors while guaranteeing every American – including Mr. Trump – the right to a fair, impartial, and transparent process, as well as constitutional free speech.

“Threats against members of juries who are just doing their legally obligated citizen service ... are shocks to the heart of our rule of law,” says Rachel Kleinfeld, a senior fellow at Carnegie’s Democracy, Conflict, and Governance Program in Washington. “Democracy can’t stand when rule of law is threatened in this way.”

For most of American history, jurors were peers with names and faces, homes and places of work. Most Americans saw jury duty as an essential civic endeavor – an act of responsibility with lives hanging in the balance. That reputation became part of a shield against retribution.

But that shield has rusted. Political polarization has challenged basic American values, norms, and institutions – including the judicial system. Now, invectives not just threaten safety, but also raise questions of how intimidation and harassments can jam the wheels of justice.

Ms. Kleinfeld says that recent steps toward accountability – such as the arrest in Texas of the woman who allegedly threatened the federal judge in Mr. Trump’s case – send an important message.

“People who believe that they can get away with anything under the cover of free speech have realized there are limits,” she says. “You can’t walk into a bank, say ‘Give me your money,’ and then just say, ‘I’m speaking freely.’”

In the 1970s, threats against juries led judges to allow some jurors at mafia trials to remain faceless. More recently, threats against the judiciary system more generally have spiked. The U.S. Marshals Service, which provides security for the federal judicial process, has seen inappropriate communications and threats against those it protects rise from 1,278 in fiscal year 2008 to 4,511 in fiscal year 2021, according to department documents.

These threats have sometimes turned into violent acts. In 2020, an attorney known for anti-feminist views dressed up as a delivery driver and shot and killed the son of federal Judge Esther Salas at her home in New Jersey, also wounding her husband. Judge Salas has since pushed for federal legislation that would offer broader protections for U.S. judges.

Last June, retired Wisconsin state court Judge John Roemer was shot and killed in his New Lisbon home by a man he had sentenced in a criminal case 15 years earlier. Police later found what they called the shooter’s “hit list,” which included the names of U.S. Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell, Wisconsin Gov. Tony Evers, and Michigan Gov. Gretchen Whitmer, according to a report from the New York City Bar.

Seeking a difficult balance

Yet there is also a risk of going too far in protecting juries. Allowing jurors to remain anonymous can throw into question the basic constitutional purpose of a jury of one’s peers, including creating a sense of accountability and legitimacy. Moreover, one survey by the Cornell Law Review found that anonymous juries are 15% more likely to return a guilty verdict than a named jury.

That means the threshold for keeping juries secret should remain extraordinarily high, says Gregg Leslie, executive director of the First Amendment Clinic at Arizona State University in Tempe.

“To say that today we can identify people more easily, therefore juries need to be secret, sends absolutely the wrong signal about our system of justice, which must remain open and trusted,” he says. “And in those rare cases when it is justified, the court has the obligation to release as much information about jurors as possible so the public will have confidence that this is a jury of peers.”

The upcoming trial in Georgia will again pit the interests of jury safety and transparent government against each other. Like most trials in Georgia – and unlike federal trials – it likely will be televised. Allowing the proceedings to be viewed on television is a bid to assure Americans that Mr. Trump and his co-defendants receive a fair trial.

“There’s an important little-d democratic value in letting people hear the evidence, see the witnesses, and digest the vast body of arguments on both sides and come to a conclusion based on facts and reality – not conjecture and courtroom sketches,” says Anthony Kreis, an assistant professor at Georgia State University’s College of Law in Atlanta.

But after the failure to prepare for the Jan. 6 attack – largely in deference to free speech concerns – law enforcement has been more pro-active in investigating threats to prosecutors, judges, and jurors.

A need to ramp up security

As threats mount, experts say the United States may have to spend more resources protecting those inside the justice system.

“Ensuring that judges can rule independently and free from harm or intimidation is paramount to the rule of law,” Drew Wade, public affairs chief of the U.S. Marshals Service, said in a statement to Time magazine.

Here in Georgia, Fulton County Sheriff Pat Labat said Thursday his office is investigating threats to the grand jurors – and taking steps to safeguard them.

“A lot of these [extremist] movements have begun to realize it’s easier to target a local election employee that no one has heard of than a federal judge,” says Jon Lewis, a research fellow at George Washington University who studies extremism and federal responses to anti-government threats. “That creates different responses, including having a really robust plan in place for what to do when they see these threats.”

“If you are only focusing on bad actors when they have a gun and are driving toward the courthouse, you risk missing the forest for the trees.”