Debt talks run down to the wire: Does it have to be like this?

Loading...

| WASHINGTON

High-stakes negotiations over the debt limit are intensifying between House Speaker Kevin McCarthy and President Joe Biden as the clock ticks down toward default on the country’s record national debt.

Though there are growing signals that they are getting closer to a deal, conservative Republicans are threatening to block it. All of which begs the question: Why is the country increasingly finding itself in this risky dance with default?

If Congress does not increase the amount the country is allowed to borrow, a step Mr. McCarthy said he will support only if paired with significant spending cuts, the United States could default as soon as June 1. The standoff has underscored the gravity of America’s current finances – and just how broken the mechanisms are for getting the nation’s fiscal house in order.

Why We Wrote This

Even as congressional negotiators near a deal with the White House on raising the U.S. debt limit, avoiding default isn’t a foregone conclusion. That’s stirring criticism of the debt limit process itself.

In recent years, budget measures have been passed largely along party lines, using a congressional loophole to get around the filibuster. Although the budget process still leaves some room for bipartisan negotiating in a divided government, recent history has left many conservative lawmakers feeling that bargaining over the debt limit is one of the few ways to tame spending.

“The debt limit is a horrible mechanism for addressing our debt problems,” says Shai Akabas, director of economic policy for the Bipartisan Policy Center in Washington. “The reason why I think we continue to have these debt limit fights is because the budget process is fundamentally broken in Congress.”

Now some are pushing to eliminate the debt limit, given the grave risk these increasingly politicized standoffs pose not only to the U.S. economy but to the global economy as well.

Fiscal jam ahead

Both sides agree the fiscal issues are real. If interest rates continue to rise, the U.S. could be forced to put 50% to 100% of its annual tax revenue toward paying interest on the national debt within several decades – leaving not a dollar to pay off debt, let alone fund myriad government programs from defense to Social Security. But they diverge over how to address the record national debt, and the deficit spending that’s fueling it.

“There’s got to be some mechanism to tell Washington that you can’t keep printing money that you don’t have,” says House Majority Leader Steve Scalise, a Louisiana Republican.

Democrats have an answer for that: increase revenue, including through taxes on corporations and the ultrawealthy.

They see Republicans as hypocritical, blaming Democratic spending without noting the impact of 2017 Trump tax cuts. Those cuts were projected by the nonpartisan Congressional Budget Office to add $1.9 trillion to the national debt over a decade, though a 2021 conservative analysis using updated data argued they were on track to pay for themselves.

Democrats add that during the Trump administration their party supported three debt ceiling hikes without demanding concessions, as the GOP is now demanding from Mr. Biden.

Last month, the House GOP passed a bill along party lines that raised the debt ceiling in exchange for bringing spending back to 2022 levels, but the bill has virtually no chance of clearing the Democratic-held Senate.

“A real solution is a bipartisan one that can pass the House and the Senate,” said Rep. Susan Wild, a Pennsylvania Democrat from a swing district, on Tuesday. She called on her GOP colleagues to moderate their position in order to “avert a crisis that is going to hurt every single hardworking American.”

Long history of debt decisions

Prior to 1917, Congress had to approve each instance of the U.S. government incurring debt. It eased those rules during World War I to give the Treasury more flexibility to finance the war. In 1939, Congress established the first debt limit, at $45 billion, and steadily raised it to $300 billion to accommodate spending on World War II, according to a timeline compiled by the Bipartisan Policy Center.

Congress has raised, extended, or redefined the debt limit nearly 80 times since 1962, almost twice as often under GOP presidents as under Democratic presidents, according to the Treasury Department.

For decades, the debt limit has been used to extract concessions over spending, with substantial success. But whereas it was once something Congress used as a check on the executive branch, it has increasingly become a tool wielded by one party in Congress against the other.

And whereas both parties used to agree to short-term extensions of the debt limit to give themselves a window to work out a broader deal, now Republicans are using the risk of national default as additional leverage to get the spending cuts they seek.

Some see that as craven politicking, with no regard for the good of the country. But others say that’s what is needed to restore the country’s fiscal strength, and thus its ability to do good for its citizens and partners abroad.

An Obama-Trump boom in debt

The national debt now stands at more than $31 trillion, with an increasingly rapid trajectory at current spending levels and interest rates. A little over half that debt was accrued during the Obama and Trump administrations.

The debt has continued to grow under President Biden, fueled by deficit spending on additional COVID-19 relief bills as well as the Inflation Reduction Act. It is now at 98% of gross domestic product – roughly four times greater, proportionally, than 50 years ago, according to the Congressional Budget Office.

CBO historical data also shows that revenue levels as a proportion of GDP have grown during that time by about 2 percentage points while spending has grown by about 7 percentage points, lending credence to the GOP claim that the growing debt is due not to abnormally low taxes but to increased spending.

“The increases of spending that we’ve seen in the last couple of years have been insane,” Rep. Mario Diaz-Balart, a Florida Republican on the Appropriations Committee, told journalists outside the House this week. “There’s a reason why we have the highest inflation in 40 years.”

In addition to growth in discretionary spending, entitlement programs like Social Security continue to get more expensive, particularly as baby boomers retire.

Even under the GOP bill passed last month, spending would still exceed revenues by about $1.5 trillion per year, further adding to the debt.

Representative Wild agrees there need to be bipartisan discussions about responsible cuts to federal spending. But that should be done separately from raising the debt limit to accommodate spending that has already been approved, she told the Monitor in a brief interview.

“The debt limit is not something that’s negotiable,” she says. “I can’t call Mastercard and say, ‘Sorry, I was just told that I can’t pay my bill.’”

The politics – and possible solutions

To the frustration of congressional Democrats, Speaker McCarthy and his fellow Republicans seem to have gained the upper hand in messaging to the American public, about 6 in 10 of whom agree that spending cuts should accompany an increase of the debt ceiling, according to several recent polls. Part of the reason the GOP may be getting through is because it’s putting it in terms of household finances.

“If you gave your child a credit card and they kept hitting the limit, you wouldn’t just raise their credit limit – you’d sit down and help them figure out where they could cut back on spending,” tweeted Speaker McCarthy last month – a point he’s been reiterating in his frequent gatherings with reporters.

White House negotiators, by contrast, have largely avoided giving press conferences – leaving congressional Democrats to try to fill the messaging gap.

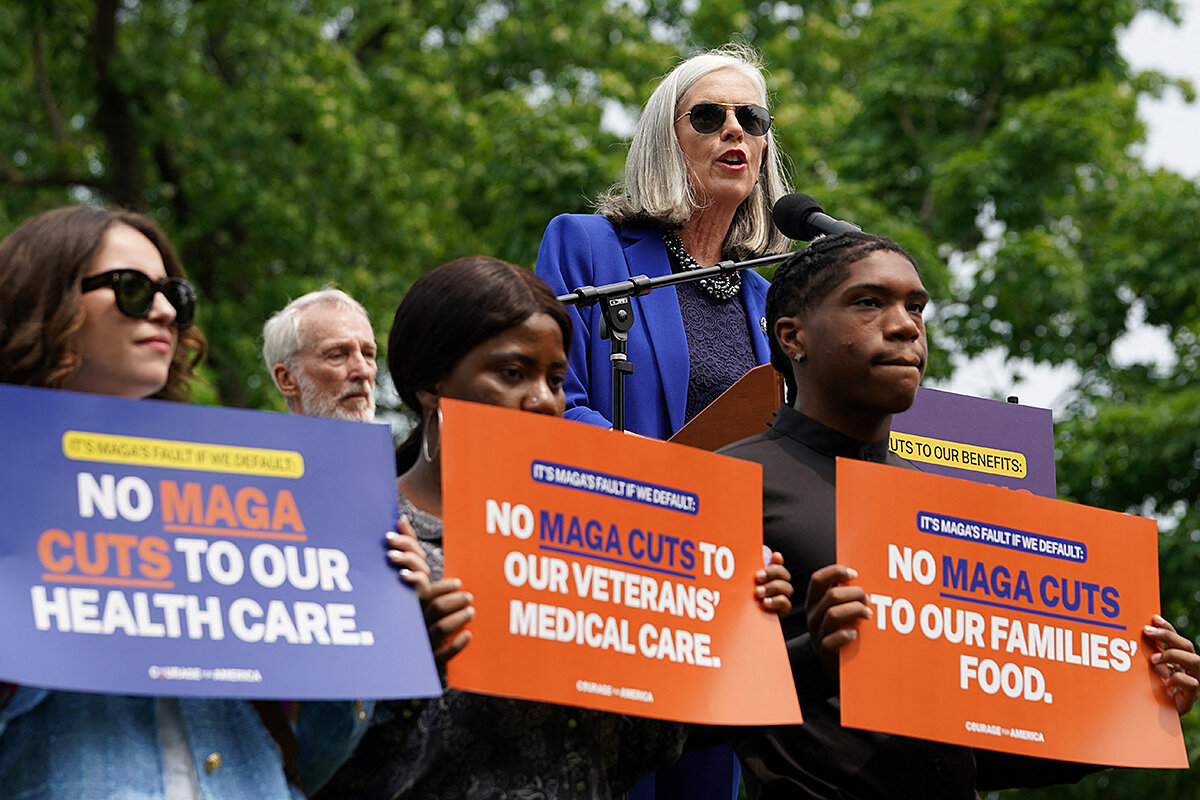

On Tuesday, Democratic Whip Katherine Clark of Massachusetts and some of her colleagues joined forces with the activist group Courage for America to push back on the GOP messaging.

“The MAGA majority wants the American people to make an impossible choice: accept devastating cuts or a devastating default,” Representative Clark said. “They manufactured a crisis so they can bully and threaten the very people they were sent to Washington to represent.”

If American voters are pointing fingers at a dysfunctional Congress, however, some of those fingers are pointing back at them – and their choice of whom to elect.

“When you support nonsense, you get nonsense,” says former Sen. Kent Conrad, a North Dakota Democrat who helped negotiate a resolution to the last major debt limit crisis in 2011 as Senate Budget Committee chairman. “So hey, maybe it’s time for the American people to look in the mirror and say, ‘Gee, how did these people get into office?’”

One possible solution, says Mr. Akabas of the Bipartisan Policy Center, would be reintroducing the 2021 Responsible Budgeting Act, which would raise the debt limit for the fiscal year in which a budget is passed. Another, proposed by the House Problem Solvers Caucus, would be to extend the debt ceiling through 2023 and appoint a commission to get U.S. finances on a more sustainable path.

“When I speak to members on both sides of the aisle, they’re just sick and tired of these fights,” says Mr. Akabas. “And they realize that we don’t get much more out of them than we would if they were held over some other policy tool.”