Reassessing US democracy: Stronger, but not out of the woods

Loading...

Is American democracy more resilient than we thought? Or has it just won a temporary reprieve?

Three weeks after elections in which democracy itself seemed to be on the ballot, those questions still hang in the air.

Before the midterms, warnings of an impending democratic crackup were rife. Most centered on Trump-backed candidates running for offices that oversee elections who said they wouldn’t have certified President Joe Biden’s victory in 2020 – raising questions about whether they might do the same in 2024. Under this scenario, the peaceful transfer of power to the winner, a bedrock of democracy, seemed imperiled by the possible elevation of election deniers in states like Pennsylvania and Arizona.

Why We Wrote This

After a relatively smooth midterm election, America’s democracy seems less vulnerable to a crisis of legitimacy than many had feared. But experts still warn of anti-democratic trends.

In the end, however, voters mostly rejected these candidates. And having lost, many of them did what former President Donald Trump did not: They quickly conceded.

The midterms also defied predictions of administrative chaos. Elections ran smoothly in nearly every district. Partisan poll watchers didn’t disrupt voting or counting. Widespread unrest, fed by social media rumors and distrust in the system, never materialized.

This orderly process, together with the defeat of high-profile election deniers, has led some to suggest that all the dire warnings about democracy in peril were unduly alarmist. “It was exaggerated and somewhat ridiculous, but that’s politics,” says Rich Lowry, editor-in-chief of the conservative National Review, who nevertheless adds that he was glad to see candidates who spread falsehoods about the 2020 election go down in defeat.

Indeed, the alarms served a purpose, helping Democrats raise huge sums of money, including from some Republican donors. The televised hearings of the House panel on the Jan. 6 attack also put the threat to democracy front and center, reminding voters of what happened after Mr. Trump lost and how political violence was unleashed on the U.S. Capitol.

“People were tired of lies about 2020. They were tired of hearing these conspiracy theories,” says Joanna Lydgate, CEO of the States United Democracy Center, a nonpartisan group that supports free and fair elections.

Still, some scholars say the need for vigilance in protecting democracy remains. It’s not just a question of who oversees elections in swing states. Other undemocratic practices, from gerrymandering to voting restrictions to dark money for campaigns, could still undermine America’s system of representative self-government. And many point to rising threats of political violence, including attacks on politicians and their families, as cause for concern.

“There is a certain path to stealing the election in 2024 that seems to be smaller, if not outright foreclosed – and that’s great,” says Zoe Marks, a lecturer in public policy at Harvard’s Kennedy School who studies authoritarian politics. “The broader question that I’m concerned with is whether or not there are other paths to stealing an election.”

Election deniers did win office in 10 Republican-run states, where they will oversee, certify, or defend future elections, according to the States United Democracy Center tracker. Many were incumbents and some faced no opponent. They include Chuck Gray, a Republican who ran unopposed to be secretary of state in Wyoming.

And of the Trump-allied election deniers who lost competitive races, not all have conceded.

In Arizona’s closely watched gubernatorial race, Republican and former TV anchor Kari Lake is contesting her defeat to Democrat Katie Hobbs, citing delays caused by the failure of ballot tabulation machines in Maricopa County, the state’s largest county. The problems led to long lines at many polling places, with impacted voters told they could either go to other stations or drop their ballot in a secure box to be counted later.

Defeated secretary of state candidate Mark Finchem, a GOP state lawmaker who sought to decertify the results of the 2020 election in Arizona, also hasn’t conceded. A recount in the attorney general race, in which pro-Trump candidate Abe Hamadeh is trailing his Democratic opponent by about 500 votes, will be held Dec. 5.

Conceding after losing an election is a democratic norm that carries no legal weight, but provides “closure” to voters, says Tammy Patrick, a former federal elections official in Arizona. “I don’t think any of us really knew how important the concession part of politics is until candidates stopped conceding,” she says, referring to the 2020 presidential election.

The quick and even gracious concessions by many candidates who’d echoed Mr. Trump’s claim that the 2020 election was stolen – a claim that multiple federal courts, law enforcement agencies, and state-level audits found to be baseless – surprised some scholars of U.S. democracy. To some, it underscores the extent to which everything that happened in the wake of 2020, up to and including the storming of the Capitol, was the direct result of one man’s willingness to subvert democratic norms.

“It puts a highlight on what an extraordinary politician Donald Trump turned out to be. It takes a certain kind of malevolent chutzpah to stand in front of the cameras and tell lie after lie,” says Susan Stokes, a political scientist at the University of Chicago and faculty director of the Chicago Center on Democracy.

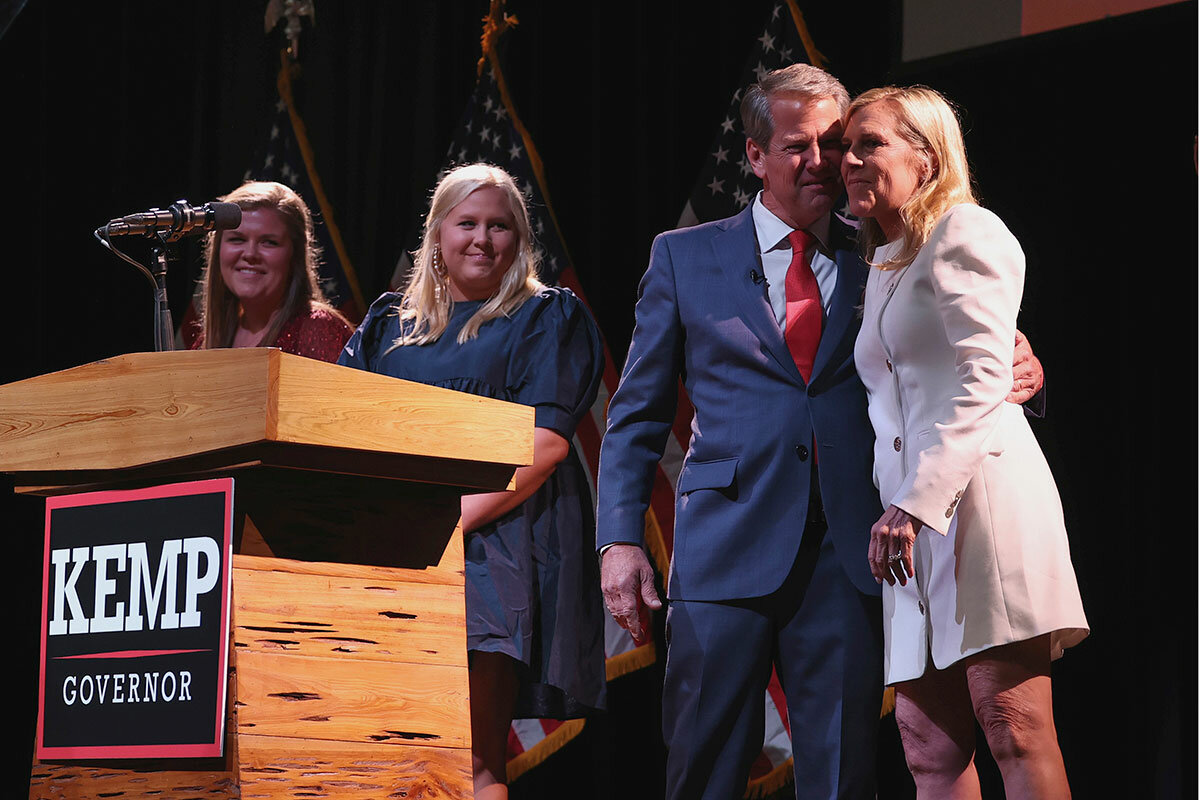

Going forward, much may hinge on how tight a hold Mr. Trump still has on the Republican Party. In 2020, GOP election officials in states like Georgia and Arizona resisted his efforts to overturn the results. Georgia Gov. Brian Kemp and Secretary of State Brad Raffensperger, both Republicans, defeated Trump-endorsed primary challengers in May and went on to win reelection handily this month.

In Wyoming, a deep-red state that Mr. Trump won by 43 points, Republican lawmakers are already pushing back against Mr. Gray, the newly elected secretary of state who claimed President Biden’s victory was illegitimate. The GOP-run Legislature is drafting a bill that would strip his office of the power to oversee elections in the state.

Mr. Gray, a Republican state lawmaker, said during his campaign that he would remove election officials who didn’t share his vision. After he won his primary, the state elections director announced he was looking for a new job.

Since 2020, election officials across the country have faced an unprecedented spike in threats and harassment, which led many to quit or retire, notes Ms. Patrick – another pressing challenge for democracy.

But she takes comfort in the defeat of many 2020 election deniers. And she notes that even those who won will be part of a complex system with multiple checks and balances that limit the autonomy of individual officeholders. “To try to overthrow the whole apple cart is difficult. It would take a whole slate of people,” she says.

One additional check on any repeat of 2020’s chaotic transfer of power would be to amend the 1877 Electoral Count Act that Mr. Trump and his lawyers tried to exploit on Jan. 6. Congress is considering a bipartisan bill to clarify how electoral votes are counted.

Some analysts say democratic norms and practices have also been slowly eroding at the state level, specifically with the partisan redrawing of congressional maps and increased barriers to voting.

Since the start of last year, 42 voting laws have passed in 21 states, says Charlotte Hill, director of the Democracy Policy Initiative at the University of California, Berkeley. In many cases, Republican lawmakers cited potential fraud to justify restrictions that Democrats say are intended to suppress Democratic-leaning voters.

Republicans counter that electoral integrity is a bipartisan concern and point to high turnout in the midterms as evidence that criticism of state voting laws has been overblown. Ms. Hill notes, however, that many of the laws have yet to go into effect, so their full consequences won’t be known until the 2024 election.

The next major test for U.S. democracy may be Mr. Trump’s bid for the 2024 GOP nomination in the shadow of potential criminal indictments. While some party leaders have been unusually critical of the former president in the wake of the disappointing midterm results, previous such instances have all ended with Mr. Trump reasserting his hold on the party. It remains to be seen whether Mr. Trump will moderate his attacks on democratic institutions, from the Department of Justice and FBI to state and local election boards, or double down to galvanize his base.

“The effort to undermine our elections has certainly taken root over the last couple of years. I don’t think it’s going anywhere,” says Ms. Lydgate.