Seeking to counter China on chips, Congress gets stuck fighting itself

Loading...

| Washington

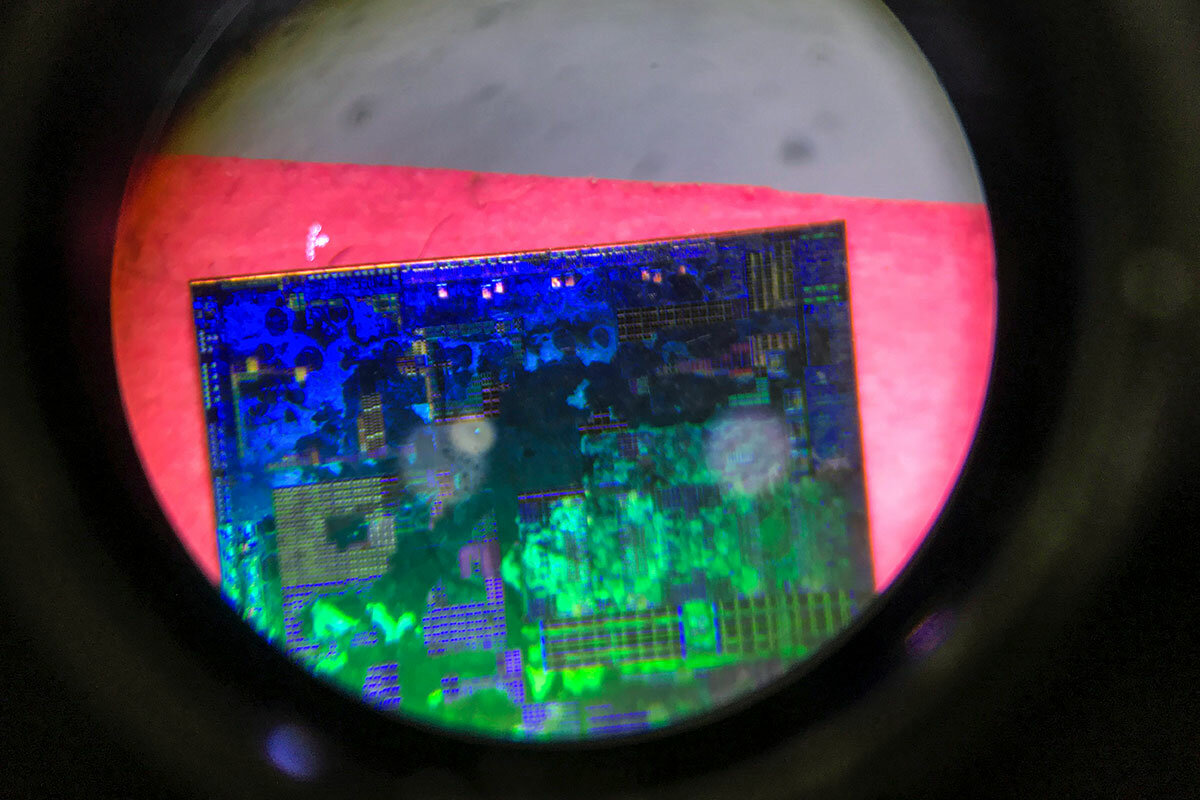

Everything Americans use with an on-off button, from dishwashers to iPhones to Teslas, likely includes a key component: computer chips.

And the problem is, America’s supply is running short. The scarcity, fueled by pandemic-related supply disruptions, has driven up prices and spurred inflation. As new cars became more expensive to make, for example, used-car prices spiked nearly 40% in the first year and a half of the pandemic.

Such economic troubles are at the top of voters’ concerns, according to polls. And the fact that the most sophisticated chips, including those needed for military equipment, are mainly made in Asia raises national security concerns.

Why We Wrote This

U.S. lawmakers are increasingly united in seeing China as a strategic adversary, and in wanting to revive homegrown chip manufacturing. Yet a trademark of the current Congress – partisan maneuvering – may play into Beijing’s hands.

Lawmakers in Congress have a proposal to address the problem by investing in facilities that would bring more chip manufacturing back to America. It’s called the CHIPS Act, and it passed the Senate with strong bipartisan support in June as part of a larger bill to increase U.S. competitiveness vis-à-vis China.

The irony is that in trying to increase America’s competitive edge, Congress has gotten stuck in partisan wrangling that plays right into Beijing’s hands.

Today, the House passed its version of the legislation 222-210. But apart from one GOP vote, Democrats were unable to win support from Republicans, who said they were caught off guard by the nearly 3,000-page bill, which includes an array of progressive priorities in addition to bipartisan measures like CHIPS.

Beijing “would love nothing more than to see us in a partisan battle over China,” says Rep. Michael McCaul of Texas, a leading GOP voice on the CHIPS Act. “What they would hate to see is if we came together and passed the CHIPS for America Act.”

Now the House and Senate will have to seek a compromise version that both chambers can support – all while companies and consumers continue to face the consequences of a chip shortage. Lawmakers who worked on the original CHIPS legislation are already frustrated it took this long to come to the House floor.

“It’s crazy that we’ve taken an extra six months while countries around the world are making decisions on these [chip] fabrication facilities that we’re not competitive with,” said Democratic Sen. Mark Warner of Virginia, speaking the day before the House vote. As a co-sponsor of the CHIPS Act in the Senate, he describes it as a “three-fer”: “It puts Americans to work, it sends a strong signal against China, and it helps with inflation because the supply chain on chips is what’s driving up the cost of cars. What part is not to like?”

Heavy reliance on Asia

America remains a leader in designing chips, semiconductors that have become increasingly ubiquitous with the development of everything from electric vehicles to thermostats connected to the internet.

But today, nearly 80% of global chip production takes place in Asia. Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co. has a near monopoly on producing the most advanced type of chips, which are used in smartphones, laptops, and military equipment. That is a vulnerability Beijing could exploit. Some see Taiwan, a self-governed island off the coast of mainland China, as increasingly susceptible to invasion. In addition, earthquakes could disrupt the island, which sits on the Pacific Ring of Fire.

“We have a very high level of dependency on a single potential failure point in Taiwan,” says Charles Wessner, a senior adviser for the Center for Strategic and International Studies’ Renewing American Innovation initiative.

So Congress would like to inject federal funding through the $52 billion CHIPS Act, a long-term investment designed to boost chip manufacturing – including of the most sophisticated type – in the United States.

“I think everybody realizes that this is a national security issue for our country,” says Navy combat veteran and Democratic Sen. Mark Kelly of Arizona, where Intel and Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co. are building new plants. “I’m not so concerned about the vacuum cleaner. It’s the fighter airplane. It’s the missile system.”

CHIPS, he says, “goes a long way toward addressing the problem.”

Senate versus House

The Senate included funding for the CHIPS Act in its U.S. Innovation and Competition Act (USICA), passing it 68-32 in June last year with support from 19 Republicans.

House Democrats say it took seven months to bring it to the floor because there was some dissatisfaction with USICA among both parties, and House committees were working on bipartisan solutions. When those efforts didn’t bear enough fruit, and it became clear that inflation was rising and likely to persist, Speaker Nancy Pelosi moved to bring a Democratic version to the floor.

“Everybody wants to get this done as soon as possible,” says a senior House Democratic aide.

On Jan. 25, Speaker Pelosi and Rep. Eddie Bernice Johnson, chairwoman of the House science committee, introduced the nearly 3,000-page America Competes Act, hailing its bipartisan development. A science committee staffer provided a list to the Monitor of dozens of bipartisan bills reflected in the act, many of which have already passed the House with strong Republican support.

“We know that we have done the homework openly and fairly,” said Chairwoman Johnson.

While Republicans acknowledge that their people on some committees, including science, had meaningful negotiations with their Democratic counterparts, they say those on many others did not. And even those who did were not included in drafting the massive legislation. Republicans have dubbed it the “Concedes” Act, because it strips out key provisions including export controls for countering Chinese military and industrial development. The legislation also adds an array of partisan priorities, among them protecting coral reefs, and incentivizing consumption of seafood from “well-managed but less known species.”

“Why did we take a focused, targeted act and subsume it into a close to 3,000-page piece of legislation that covers everything from wet suits to shark fins?” asks Nadia Schadlow, former deputy national security adviser for strategy and a senior fellow at the Hudson Institute.

Representative McCaul says he told the administration it couldn’t use CHIPS as a carrot to get GOP support for such partisan policies. He says that in a phone call with Secretary of Commerce Gina Raimondo just days before Speaker Pelosi introduced the America Competes Act, the secretary had expressed support for bringing CHIPS to the House floor as a stand-alone bill.

A Commerce Department spokesperson said in a statement to the Monitor that while Secretary Raimondo appreciates the congressman’s advocacy, she “has been clear in both public and private conversations that the best way to secure that funding is as part of a larger package that also spurs broader scientific innovation and secures supply chains that underpin our economic and national security.”

A year into President Joe Biden’s term, as his approval rating hovers just above 40%, some Democrats are frustrated by the party’s perceived overreach – striving to pass sweeping legislation rather than focusing on pragmatic solutions that will help voters.

Rep. Elissa Slotkin, a Michigan Democrat, supported the House bill but earlier this week voted against a related procedural measure as a “shot across the bow.”

“After letting the CHIPS Act lay dormant in the House for more than 6 months, the leadership rushed a new version in the past week, allowed Republicans to politicize what is a largely bipartisan bill, and elevated expectations on what will actually pass into law,” she said in a statement, calling on Democratic leadership to get serious about compromise. “Passing a bill just through the House will do nothing to get microchips to the auto plants I represent.”

China’s strategic goals

Some see China’s growing economic influence as part of a larger Chinese Communist Party strategy to undermine America’s model of government and its global leadership.

“Our nation must be united and unwavering in asserting our global leadership and holding the CCP accountable,” said GOP Rep. Young Kim, noting that the House bill came to the floor as China is opening the 2022 Beijing Winter Olympics and using that world stage to project its image as a rising power.

China consistently rejects U.S.-style democracy and perceived unfairness in U.S. policies, says Bret Schafer, who follows foreign messaging and disinformation at The German Marshall Fund’s Alliance for Securing Democracy. So Mr. Schafer was surprised to see that Chinese state media and diplomats have had almost nothing to say about what is unquestionably an anti-Chinese bill.

“I think they may avoid touching this because I think it’s in China’s interest to not have this passed soon,” says Mr. Schafer. “For Chinese state media to show that this is a real sore point for China could be seen as a way of catalyzing both sides to come together and pass it.”

Staff writer Dwight A. Weingarten in Washington contributed to this article.