Democrats and Republicans vie to be ‘the party of parents’

Loading...

| Washington

What do parents want?

That question is urgently top of mind for both Democrats and Republicans on Capitol Hill in the wake of Tuesday’s elections. Just one year after President Joe Biden won Virginia by 10 points, the GOP captured the governor’s seat there and nearly upset Democratic Gov. Phil Murphy in deep-blue New Jersey – in part by tapping into parental anger over education policy, and promising to give parents more authority over critical decisions in their children’s lives.

Democratic leaders, who were unable to pass two key bills last week that many thought would have helped the party on Election Day, are pushing hard to get them across the finish line and shut down Republican efforts to brand themselves as “the party of parents.” They are emphasizing the many measures in the president’s Build Back Better bill aimed directly at families – including an extension of enhanced child tax credits, subsidized child care for lower-income families, and universal pre-K.

Why We Wrote This

Amid a pandemic and a national racial reckoning, parents are rethinking the role government plays in their children’s education, well-being, and opportunities. Both parties are striving to tap into that.

“It’s about the children, about their parents,” said Speaker Nancy Pelosi on Thursday, noting that a month of paid family and medical leave – an issue particularly important to her as a mother who gave birth to five children in six years – has now been added back to the bill after being cut for cost reasons.

“Our belief is that when you invest in people early – whether it’s pre-K, whether it’s paid leave, whether it’s education – you are helping them to become fully self-sufficient,” says Rep. Pramila Jayapal of Washington, the chair of the Congressional Progressive Caucus.

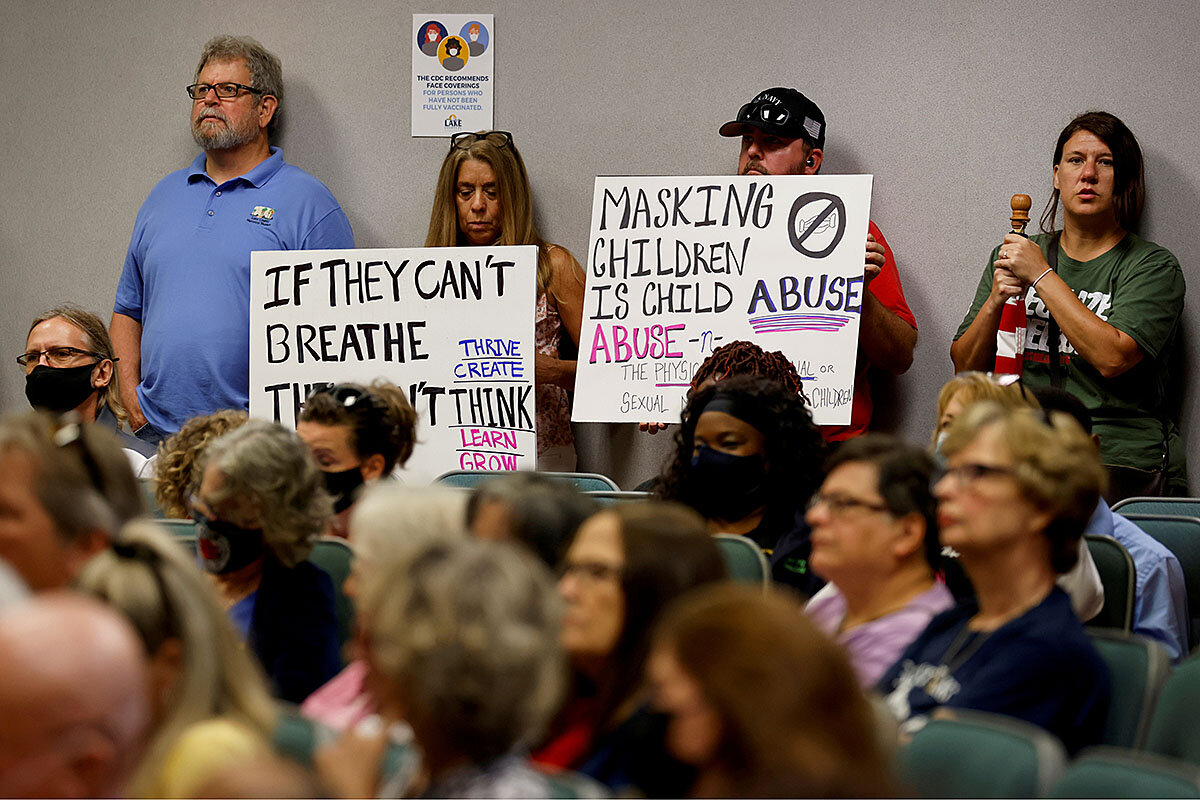

But Republicans, basking in wins from Virginia to New Jersey to Seattle, say Democrats are failing to heed the lesson of Tuesday’s results: that their sweeping social reforms are not resonating with the needs and concerns of American parents. They chastised Democrats for pushing the U.S. attorney general and FBI to monitor school board meetings, which have seen heated debates over COVID-19 regulations and curriculum changes surrounding race and identity. They also argue the proposed expansions to the social safety net will end up hurting parents financially, by driving up the cost of everything from gas to groceries to winter heating bills.

The GOP is already looking to replicate Virginia Gov.-elect Glenn Youngkin’s parent-focused campaign in races across the country as it looks to 2022, with House Minority Leader Kevin McCarthy promising to soon unveil a “parents’ bill of rights.”

“Youngkin’s success reveals that Republicans can and must become the party of parents,” wrote Indiana Rep. Jim Banks, chairman of the largest conservative GOP caucus in the House, in a memo to his members. “Parents brought real energy in Virginia and we would be wise to listen and seek to understand their concerns.”

How best to help parents, children

At the heart of the debate is a fundamental difference in the parties’ views about the role of government. In recent decades, Democrats have worked to create a more robust social safety net, pointing out that America lags far behind other developed nations in that regard. They argue that at a time of vast income inequality – which has been exacerbated by a pandemic that disproportionately hurt the working class – more government support is needed to ensure that every child has an equal chance to succeed.

“We are a nation that underinvests in our children. We have an opportunity now to do a whole lot better,” says Sen. Elizabeth Warren of Massachusetts, who has recounted how she was only able to launch a promising law career because her aunt came to be her children’s live-in caregiver for 16 years.

“We’re trying to make an investment in children, and make it possible for parents to be able to work, to finish an education, to start a small business – but that takes a bigger infrastructure,” she says. “We have tried the Republican approach for far too long, and we have too many children in poverty in the richest nation on earth. And that’s fundamentally wrong.”

Republicans see such government programs as inefficient, susceptible to exploitation, and eroding the role of faith-based institutions in supporting those in need. They blame government benefits for creating a dependency that undermines the dignity of individuals and disincentivizes work and marriage. They also argue that things like education and child care are best addressed at the local level, rather than by a federal government that may be thousands of miles removed and is unable to pinpoint the most effective or cost-efficient approach.

Democrats often criticize that as a do-nothing approach that lacks compassion for the struggles of working- and middle-class families. But Republicans say they have more faith in individuals than in a federal bureaucracy to meet the needs of those struggling and that the role of government is to empower them to do so – in part by staying out of their way.

“I find that the government’s far less compassionate than the church, and in some situations, I think, compassion that comes from people of faith is oftentimes overlooked by our own government, particularly in recent years,” says GOP Sen. Kevin Cramer of North Dakota, who sits on the Senate Budget Committee chaired by Sen. Bernie Sanders. “You’ve seen an increase in the government taking care of people and a decrease in the church taking care of those same people, either out of necessity or discouragement.”

The question of work requirements

These ideological differences have come to a head over Democrats’ proposed reforms that would delink a work requirement from certain benefits, including for children. Republicans say Democrats are exploiting the pandemic to push through permanent changes that would foster greater dependence on government. One key area of disagreement is a plan for the IRS to send monthly child tax credits to parents through direct deposit or money on a debit card, without the sort of face-to-face meetings that used to be part of such benefit programs and could bring to light other issues, such as unpaid child support or domestic violence, so that they could be addressed.

“President Biden and the Democrats are weaponizing the temporary COVID relief as a back door to create permanent new welfare-without-work programs that foster greater dependence on government and pay people more to stay at home,” said Rep. Jackie Walorski of Indiana, a member of the House Ways and Means Committee.

A nonpartisan congressional study found that work requirements could improve incomes and financial stability in some cases, but the effectiveness of such measures varied significantly based on the type of benefit and whom it aimed to help.

Democrats say that the Build Back Better bill includes numerous provisions to support greater workforce participation, and argue that work requirements create an undue administrative burden – adding to the administrative cost of the programs and preventing struggling Americans from getting the help they need in a timely way.

“Most people, the vast majority of people, are trying to do the best for themselves and for their families, and very much want to be independent – that’s my fundamental belief,” says Representative Jayapal. “So we should try to make benefits as universal as possible, make them as easy as possible, not saddle them up with a bunch of work requirements and other things that prevent the most vulnerable from actually getting the benefit.”

Representative Jayapal has taken a strong stance for ensuring that progressive priorities are included in the Build Back Better Act, and has repeatedly said in recent weeks that her 96-member caucus would not vote for a related bipartisan infrastructure bill until those priorities were agreed to not only by House Democrats but also by all 50 Democratic senators.

Speaker Pelosi has twice been forced to delay a vote on both bills due to progressives holding out for a better deal. Now, some moderates are demanding an assessment from the Congressional Budget Office that the bill really will be paid for through new taxes and stepped-up enforcement for corporations and wealthy individuals. That would take an estimated two weeks.

The speaker said Thursday morning that the nonpartisan Joint Committee on Taxation had just determined that the bill would indeed be paid for. But when asked about when she expects to hold a vote, she said, “I’ll let you know as soon as I” – and she paused – “wish to.”