‘It’s just chaos.’ One family’s struggle to make the new normal work

Loading...

| Richmond, Va.

Six-year-old Abilene Crandall is climbing up the walls. Literally.

Under normal circumstances, at this time on a Wednesday morning, she would be in her kindergarten classroom. Her older sister, Sonoma, who has left her dining-table-turned-desk to watch Abilene hop her way up the door frame, would be having a “morning meeting” with her third grade classmates.

And I would be traveling the country, covering the 2020 presidential election for the Monitor. But now I’m in the Crandalls’ kitchen, wondering at what point I should intervene in the wall-scaling.

Why We Wrote This

From home-schooling kids to trying to save a business, our reporter’s “quarantine family” is dealing with the same challenges as many. Facing an uncertain summer, they’re now relying on each other in new ways.

The COVID-19 pandemic has turned Americans’ lives inside out and upside down. Routines of work and school have been disrupted, along with most social interaction. Families have been confined at home in what’s shaping up to be the longest, most intense stretch of togetherness in anyone’s memory.

Tasked with finding a family to profile in this “new normal,” I realized I might as well focus on my own.

Editor’s note: As a public service, all our coronavirus coverage is free. No paywall.

While I may not be related to the Crandalls, we consider ourselves family. Six years ago, when my sister went off to college, my mom began working for them as a nanny. Our families have been intertwined ever since, sharing holidays, wiggly teeth, promotions, and setbacks.

During this crisis, we decided to “double bubble,” or quarantine together. Between us, there are two elementary school students, a health care worker, a small-business owner, a college professor, a middle school art teacher, and a political reporter (me) suddenly living at home again.

We are better off than most. We have jobs, internet access, and plenty of food. We are all healthy.

But that doesn’t mean life is easy right now. Our finances are tighter. Tired, bored, and anxious, we’ve been fighting more than usual. The family vacation at Virginia Beach in June is canceled.

Like many states, Virginia is just beginning to reopen. Still, we’re staring at a summer of uncertainty. What will the coming weeks and months look like? What activities will be allowed? What will actually feel safe?

One thing is already clear: Like many families around the world, we are learning how to rely on each other in entirely new ways.

Wednesday

“OK, Abs, five-minute countdown,” says Kurt Crandall at 8:52 a.m. He’s exaggerating the time until the at-home school day begins, but Abilene – who is still in her pajamas pirouetting through the kitchen – needs the extended heads-up.

Over the next eight minutes, the girls do little to prepare. Sonoma braids my hair. Abilene cries because she wanted the hairbrush first. Then Abilene remembers her new mermaid doll and proudly shows me her glittery tail.

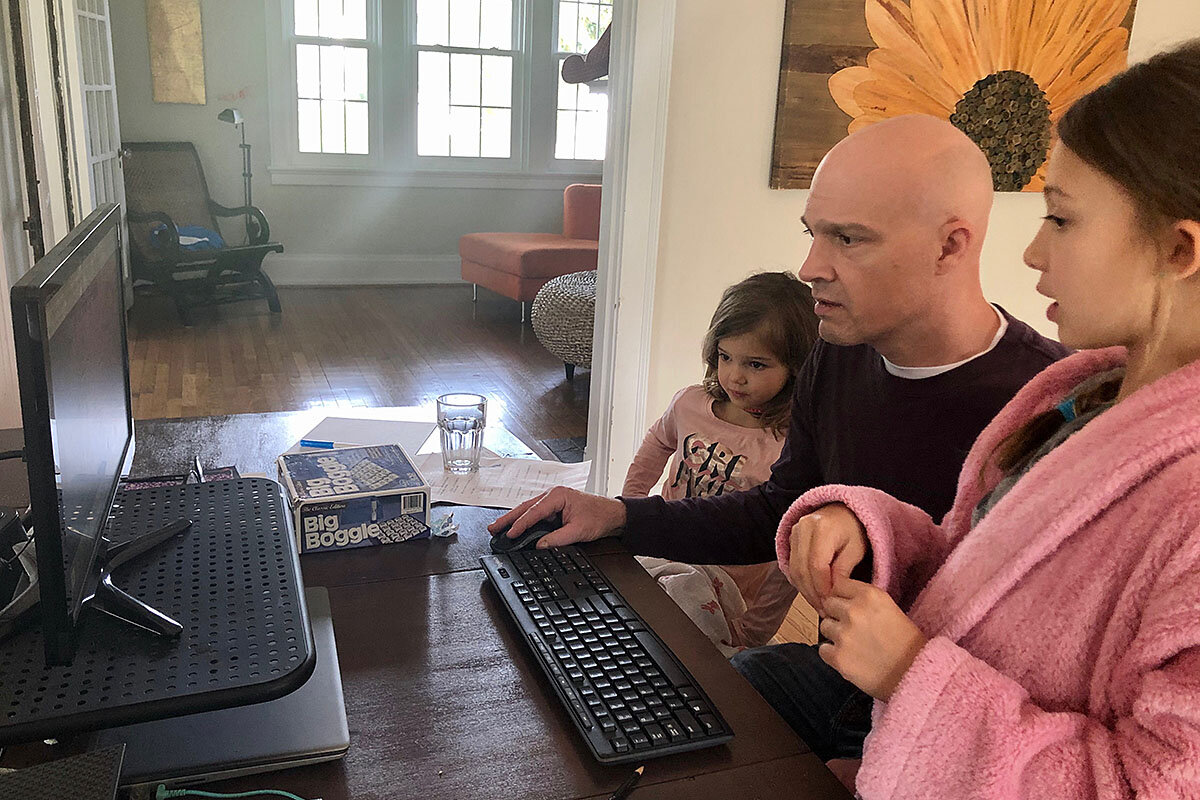

Kurt plays the sound of a school bell from a YouTube video on his phone. “OK, go to your work stations.” On his third ask, Sonoma ambles toward the dining room table, which is piled high with loose worksheets and a laptop. Since the dining table has become a third grade classroom, the family has been eating meals together outside or standing around the kitchen counter.

Kindergarten is in the adjoining room, where Abilene plays reading games on another computer. The girls’ school received a grant to distribute laptops, which Kurt picked up in an eerily empty elementary hallway, winter snowflakes still decorating the ceiling.

“Come. And. Run. With. Me. Away. We. Go,” says Abilene robotically, her index finger tracing the computer screen.

A piece of white paper is tacked to the opposing wall with school subjects penciled in a grid of 45-minute time slots. Kurt, nodding to the paper, says that plan lasted for about a week.

“Emotionally, if they aren’t in a good space, it doesn’t matter what kind of schedule you’ve drawn up,” he says.

Kurt, a psychology professor at Virginia Commonwealth University, has been teaching his students virtually since VCU closed its campus in the second week of March, while also educating his two young daughters – a job he splits with my mom (who is taking a semester off as a middle school art teacher). Stephanie works as a nurse practitioner at VCU’s Massey Cancer Center.

At first, when the penciled school schedule was still in play, Kurt would try to sneak away periodically to send an email or grade an assignment. But invariably, there would be a fight to break up, a computer to fix, or a worksheet that needed explaining. One day, when trying to record a lecture, the girls interrupted him six times before he gave up.

“It’s almost impossible,” he says, shaking his head. He just submitted his students’ final grades and is now teaching a summer course. Just as the girls miss learning in their classrooms, Kurt misses teaching in one.

“Everyone keeps saying, ‘Oh, you’re an educator – it must be easy to teach the kids,’” says Kurt, rubbing the back of his head. “But this is totally different.”

“What’s a proper noun?” Sonoma yells through the house, while Abilene continues to read aloud just a few feet away. “You. Too. Can. Run.”

Sonoma has Zoom meetings with her third grade class in which her teacher asks them to share their “peaches and pits” – the good and the bad. She has a lot of pits these days. It’s a pit that her class doesn’t get to perform the play they’d been practicing. It’s a pit that she doesn’t get to have a “real” math class (math is her favorite). It’s a pit that she doesn’t get to play at recess with her friends.

But one of the peaches, she adds, are the new friends she’s made in her neighborhood. Before the quarantine, kids on her street would ride bikes separately after school. But now, every night, all the kids ride bikes together – 6 feet apart.

Thursday

At 9:40 a.m. my mom opens her phone and begins to cry. Her uncle Bruce, my grandfather’s younger brother, passed away. My grandfather was unable to travel from Florida to Connecticut to say goodbye because of COVID-19, and my mom won’t be able to hug her cousins at a funeral.

That’s the hardest part, says my mom, holding her eyes in her palms. Suddenly, we hear the sound of the Crandalls’ car crunching our gravel driveway. My mom teaches Abilene and Sonoma on Tuesdays and Thursdays.

“I’m used to turning my life off when I walk in a classroom,” says Mom, who still has tears in her eyes as the girls run toward the house. But this – running a one-room schoolhouse with a kindergartener, third grader, and 27-year-old all working at the same kitchen table – is totally new.

Mom takes the tutoring seriously. But it’s changed her relationship with Sonoma and Abilene.

“I’m no longer the fun pseudo-grandmother,” she says. “I feel terrible when I hear they don’t want to come here because I make them do schoolwork.”

When the girls get inside they immediately split up to wash their hands: Abilene to the bathroom and Sonoma to the kitchen. Abilene sings “Happy Birthday” while rubbing the soap between her dimpled hands.

The girls settle into their seats at the kitchen table with their backpacks, which still jingle with the keychains they would trade with their friends on the bus. Like at home, school at Dido’s (as they call my mom, Diana) started out on a schedule. But now, as with Kurt’s penciled schedule hanging on the wall, it’s mostly aspirational.

Sonoma works on long division worksheets as Abilene jumps from notecard to notecard on the ground, identifying “sight words.” Later, they investigate a slug on the porch and Abilene practices karate in the yard. (“Mom and Dad say I can start taking lessons as soon as the corona is over.”) They video chat with my sister Isabelle, in Portland, Maine, and the girls ask when she can come home to visit. None of us know the answer.

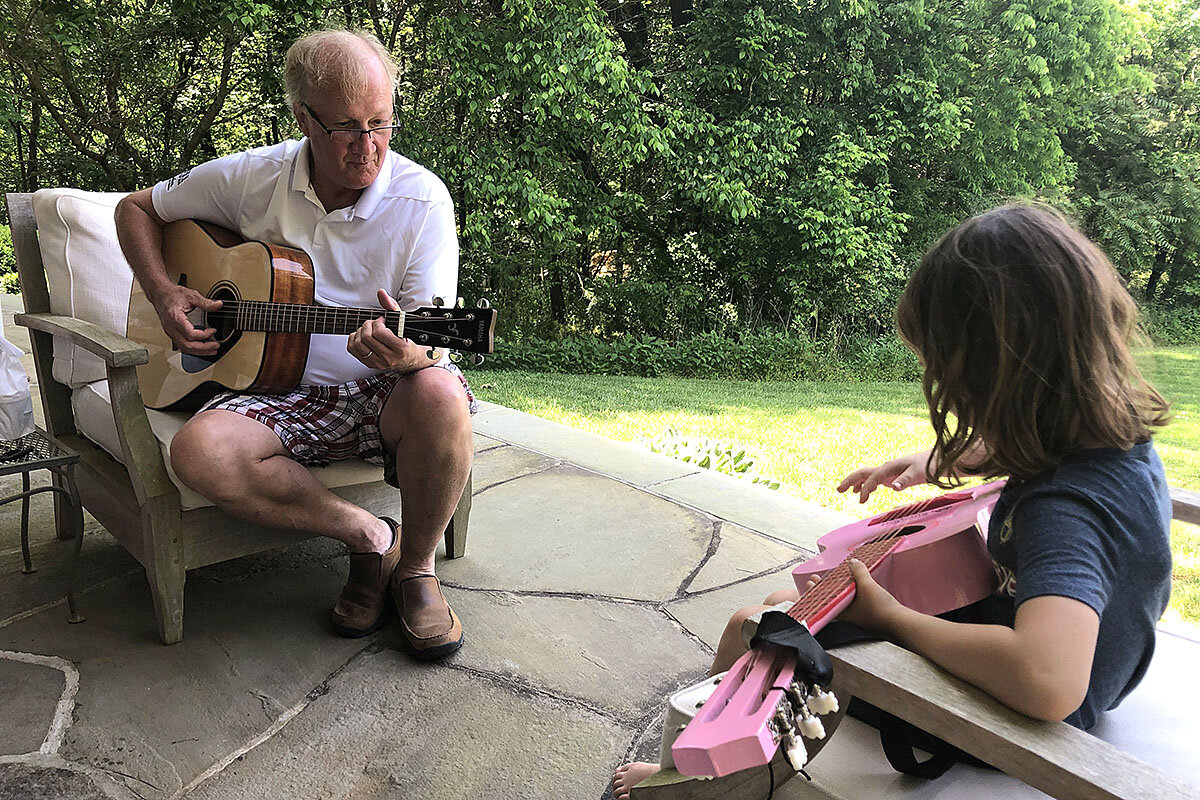

When it’s time for the girls to leave, Abilene, holding her hot-pink guitar that my parents got her for Christmas, pouts. Stew-Stew (my father, Stewart) had said he’d try to come home early from work so the two of them could play together. But he hasn’t made it back yet.

My dad, who owns a meeting planning business for medical associations, had all of his 2020 meetings canceled – and with them, all of his hotel commissions. When the PPP (Paycheck Protection Program) from the Small Business Administration was announced, he conferred with his bank and did practice applications.

We were on a walk when he learned the application was live, and he handed me our dog’s leash and jogged home. Days, then weeks, went by, with my dad refreshing his PPP “dashboard” every few minutes hoping each time to see “APPROVED.” He left the browser open on his computer. He left the dinner table to go refresh the page.

His bank was late with their applications, and the first funding ran out. No loan came. He cut his salary. He cut his employees’ salaries. He fired a woman he considered a friend. I saw my dad cry for the first time since my grandfather died, 14 years ago.

On the second round of PPP funding, five weeks after he had submitted his application, his loan was approved. Still, it’s not enough to cover the loss of business. And he’ll have to pay part of it back, because he can’t afford to restaff at the level required to make it a grant.

“At a time when I thought I’d be thinking about retirement, I never thought that I’d have to completely retool my business and give it a whole new direction,” says Dad. “Now I’m reimagining everything in a virtual world.”

He’s been working long hours to make his fall meetings virtual, through apps and livestreams. But while meetings may be virtual for now, he doesn’t think they will be forever. He compares it to 9/11: Post-COVID won’t look like pre-COVID, just like security for flying became totally different after the terrorist attacks. But we still fly.

“People will always want to be together in person, and we’ll have that again,” says Dad. “It’s going to take some time, but it’s going to come back.”

Friday

Stephanie is still in her scrubs when she walks in the Crandalls’ door, takeout dinner in hand.

“What used to be organized chaos is now ...” she interrupts herself to grab their puppy, Luna, before she runs out the front door.

“What used to be organized chaos is now just ...” she interrupts herself again, seeing that Luna peed on the floor, and walks to the kitchen to grab a rag.

“It’s now just chaos.” She takes the rag back to the kitchen, where she begins to divvy up food for the girls. Work has been so busy that Stephanie often forgets to eat lunch, but she doesn’t think about her own hunger until Kurt brings her a plate.

“As a full-time working mother, life never really felt truly ‘manageable.’ But now, with the added responsibilities to solely educate, exercise, discipline, entertain, and nurture our children – at times it all seems impossible,” says Stephanie, holding Luna with one hand and trying to eat dinner with the other. “I either need to give up sleep or find another eight hours in my day.”

She worries about her daughters’ education, their socialization skills, and their emotional health. But her job at the Cancer Center helps keep things in perspective: Her daughters are healthy and they are loved. Still, she feels guilty. As a health care worker, she’s been working long hours, and her daughters will likely have to stay socially distant longer than their friends.

And she’s worried about the future logistics of everything. Stephanie and Kurt received an email today that summer camp is canceled – something the girls had been looking forward to and the parents had been relying on.

What will they do for child care? Kurt is teaching a virtual summer course. Maybe Dido can keep watching them a few days a week.

“What if this goes on for another year? Life the way we are living just isn’t sustainable,” says Stephanie. “I need to see the light at the end of the tunnel.”

Saturday

In my “old life,” (as Abilene calls our pre-COVID past) I was attending three or four political rallies a day, standing shoulder to shoulder with voters in hot school gyms. At night I’d check into a hotel – forgetting, almost daily, to text my mom when I was off the road and in my room. Now I hug my mother every evening before falling asleep surrounded by old high school photographs and participation medals.

On Saturdays, when I was home in Washington, I’d walk through my neighborhood to a yoga class, FaceTiming the Crandalls on my way. Now I finish a run to find Abilene and Stew-Stew playing their guitars together on our front porch.

Our family, like almost all families, has had plenty of pits the past few months. But we’ve also had peaches. My mom taught Abilene the months of the year, and I taught my dad how to properly make iced coffee. Abilene rode her bike without training wheels for the first time, and my mom and I planted a garden together, like we used to do when I was younger.

As I play Boggle with Sonoma in the afternoon sun (she beats me), Abilene lays her head in my lap, waxing on about the superiority of orange popsicles.

“They really are the best,” says Abilene. “Sometimes you have to dig for the good ones. But they’re always in there.”

Editor’s note: As a public service, all our coronavirus coverage is free. No paywall.