Block the vote? The battle over ballots and the future of American democracy.

Loading...

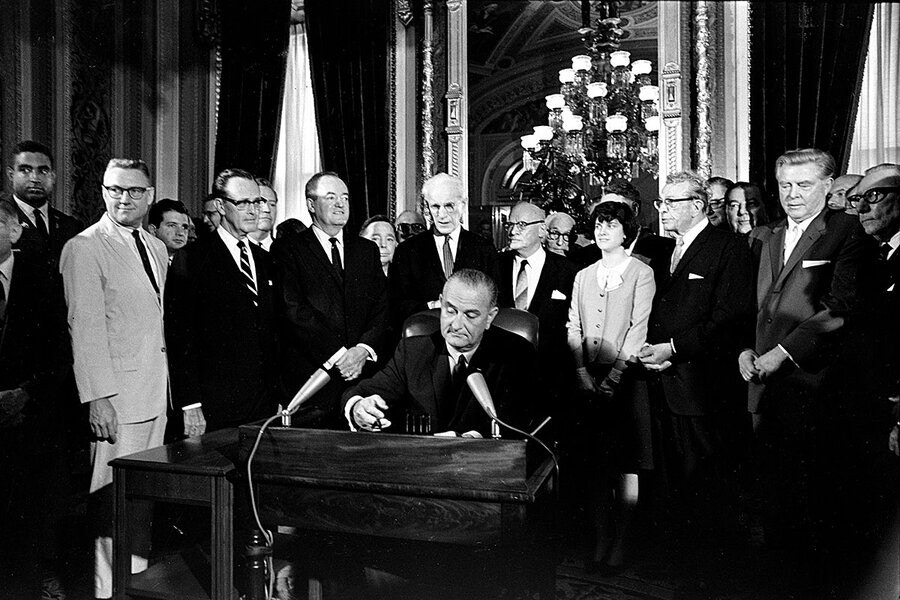

President Lyndon B. Johnson used 50 pens to sign the Voting Rights Act into law. Television footage of the Aug. 6, 1965, ceremony shows the president putting each to paper for a moment, scratching perhaps a half-letter, and then swapping the instrument out for new. When finished, he handed the pens to some of the famous figures gathered around him. Sen. Robert F. Kennedy got one. So did the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. So did civil rights activist and future member of Congress John Lewis.

Most pen recipients felt it was one of America’s finest hours. The law put federal muscle behind African Americans’ long struggle for equal voting booth access – and the political power that access bestowed. But Johnson’s own feelings that day were complicated. His daughter Luci Baines Johnson later told journalist Ari Berman, in an interview for his voting rights history “Give Us the Ballot,” that LBJ felt both victorious and afraid.

President Johnson knew he had just transformed the political structure of the nation, in ways both predictable and unforeseen. He could no longer control what would happen, the progress and the inevitable backlash, and how those might balance.

Why We Wrote This

As partisanship becomes more correlated with demographics, voting itself is once again a crucial front in the battle between the two parties, with Democrats pushing for greater access and some GOP-led states tightening requirements. Eighth in our ‘Democracy Under Strain’ series.

“It would be written in the history books. But now the history had to be made,” Ms. Johnson said.

Fifty-four years later, a renewed and intensifying struggle over ballot access and voting power is shaking the intricate structure of American democracy.

In the short run, the vote – who gets it, who doesn’t, what it’s worth – is almost certain to loom large in the 2020 elections. Top Democratic presidential contenders have all criticized recent GOP-led tightening of some state voting laws, claiming these changes are partly intended to make it harder for minorities to cast ballots.

“You’ve got Jim Crow sneaking back in,” said former Vice President Joe Biden in a speech in South Carolina on May 6, evoking the racial segregation laws of the past.

In the long run, this conflict could redraw the battle lines between America’s two big political parties during a period of rapid demographic change. That’s why Democrats made it their first order of legislative business after retaking the House in the 2018 midterms, passing H.R. 1, a sweeping bill that would establish national automatic voter registration, outlaw the “purging” of voter rolls, and in general ease and expand ballot access while countering some state-imposed voting barriers.

Voting access is becoming a crucial front in what CNN political analyst and journalist Ron Brownstein has dubbed a broader war between the Democratic coalition of transformation, composed of groups comfortable with rapid racial and cultural change, and the Republican coalition of restoration, reliant on voters who aren’t.

More and more, American electoral politics seems correlated with demographics. The modern Democratic Party is increasingly made up of minorities and young people, and thus has a direct interest in making voting as easy and widespread as possible. Republicans, conversely, are dependent on white people and older voters, demographic groups already more likely to cast ballots. The GOP thus has a direct political incentive to tighten rules and restrict electoral access.

“Fear of the increasing diversity of America is driving this,” says Carol Anderson, chair of African American studies at Emory University and author of “One Person, No Vote: How Voter Suppression Is Destroying Our Democracy.”

Many Republicans reject this framework. Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell has flatly refused to bring to the floor a Senate version of H.R. 1 – or, as he calls it, the “Democrat Politician Protection Act.”

“It’s an attempt to rewrite the rules of American politics in order to benefit one side over the other,” Senator McConnell said on the Senate floor. The bill is a nakedly partisan attempt to grow Washington’s power over Americans’ political speech and elections, the Kentucky senator charged. It would impose onerous and confusing regulations on states and localities, “while making it harder for [them] to clean inaccurate data off their voter rolls, harder to remove duplicate registrations, ineligible voters, and other errors.”

The larger conservative position is that America has come a long way on voting, thanks to the Voting Rights Act and other massive changes, and the country and its laws should recognize that. This was the view underpinning the majority opinion in Shelby County v. Holder, a pivotal 2013 Supreme Court decision that freed nine mostly Southern states to change their election laws without obtaining advance approval from the federal government.

When the Voting Rights Act passed in 1965, voter registration of African Americans in Mississippi was 6.4%, wrote Chief Justice John Roberts in the majority opinion. By the 2004 election, Mississippi’s black registration rate was 76%, 4 percentage points higher than that of white people.

“Our country has changed,” Chief Justice Roberts wrote in the opinion. “While any racial discrimination in voting is too much, Congress must ensure that the legislation it passes to remedy that problem speaks to current conditions.”

The ‘preservative’ of all rights

Voting is fundamental to the exercise of democracy. If there were no votes, how would the collective will of eligible citizens be expressed? Justice Roberts, in his 2005 Senate confirmation hearing, noted that voting was the “preservative” of all the other American rights. “Without access to the ballot box, people are not in a position to protect any other rights that are important to them,” he said.

Given that, it’s perhaps surprising that the Founding Fathers did not leave behind a bit more instruction on the issue. The Constitution did not guarantee voting rights for Americans. Instead, it allowed the states to set their own voting rules.

At the time of the Constitution’s ratification, most states limited voting to white male property owners. By some estimates, these eligible voters constituted only 6% of the nation’s population. Democracy, indeed.

Suffrage is a “part of the Constitution that has not aged well,” wrote George Mason University political scientist Jennifer Victor in a recent Vox series on the document’s flaws.

Since 1789, periodic waves of reform have greatly enlarged the eligible U.S. voting population. In the 1800s, many states struck the “property owner” requirement, opening up voting to most white males. In 1870, the ratification of the 15th Amendment to the Constitution technically gave all African Americans, including former slaves, access to the ballot. In response, Southern states adopted poll taxes and literacy tests, and employed open violence to disenfranchise African Americans and retain white political hegemony.

Some states opened the voting franchise to women in the decades before and after the turn of the 20th century, but women weren’t fully allowed ballot access until the passage of the 19th Amendment in 1920. The most recent reform wave crested with the 1965 Voting Rights Act, which banned discriminatory voter qualification practices, and authorized deployment of federal officials to register voters and oversee elections in areas with a history of blocking minorities from the polls.

A key enforcement provision of the Voting Rights Act ordered states with a poor minority voting record, most of them Southern, to ask Washington for permission before doing almost anything to change voting procedures, from moving a polling place to redrawing legislative districts. It’s this part of the law that the Roberts court deemed no longer necessary and struck down in 2013.

In the context of the long rise of democracy throughout the Western world, the voting record of the United States is mixed. The U.S. was indeed one of the first democratic countries to expand its electorate by knocking down explicit economic barriers to political participation, writes Alexander Keyssar, a Harvard professor of history and social policy, in his book “The Right to Vote: The Contested History of Democracy in the United States.” Alexis de Tocqueville and other foreign observers were struck by what they perceived as the nation’s powerful democratic spirit in the early decades of the 1800s.

But the U.S. was also unusual in that it experienced a contraction of voting rights as Southern segregationists essentially negated the 15th Amendment following Reconstruction.

“Despite its pioneering role in promoting democratic values, the United States was one of the last countries in the developed world to attain universal suffrage,” writes Dr. Keyssar.

A tale of two kinds of states

Today, the story of voting rights in America is largely a tale of two kinds of states, moving in two different directions.

Some states – mainly but not exclusively blue ones – are adopting measures to make it easier to register and vote. Automatic voter registration, for example, is a system where citizens who interact with government agencies are automatically added to the voter rolls, or automatically have their address or other voter information updated, unless they opt out of the process. Fifteen states covering about a third of the U.S. population, from Vermont and New Jersey to Nevada and California (plus the District of Columbia), now have some form of automatic registration, according to data from the Brennan Center for Justice at the New York University School of Law.

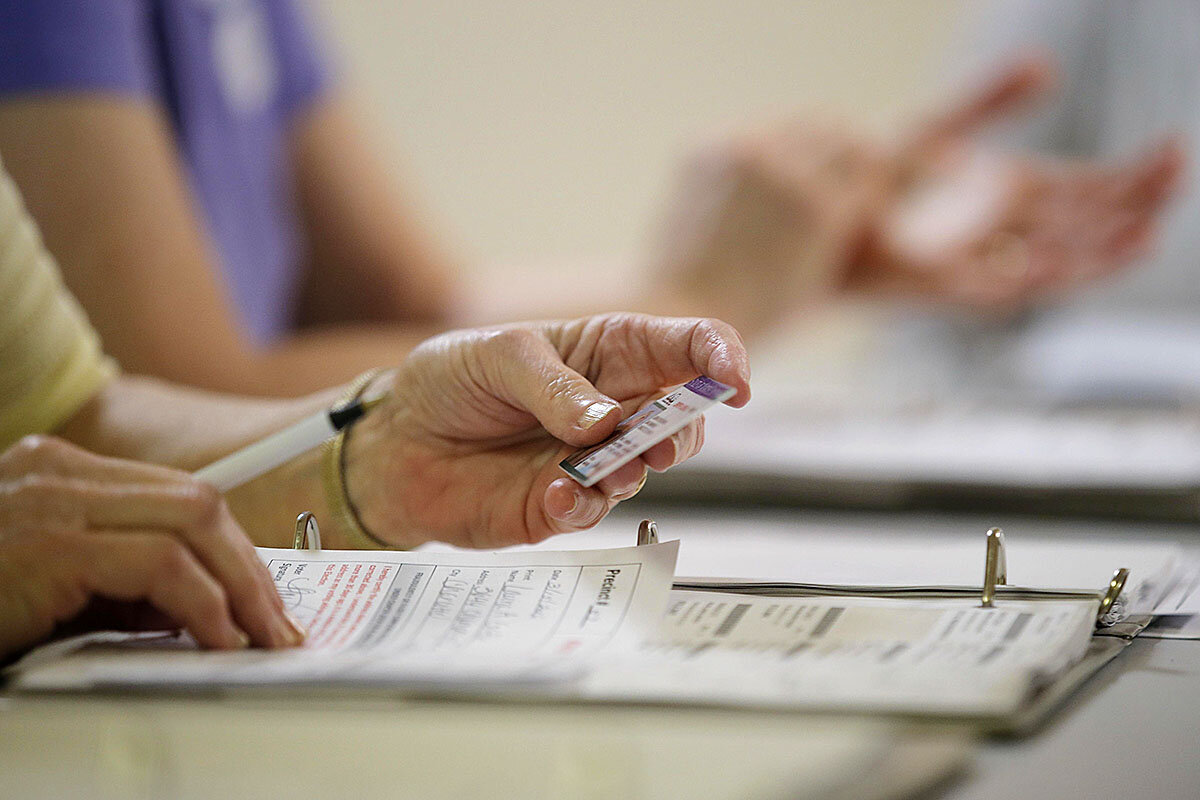

Other states – mainly but not exclusively red ones – are going in the opposite direction and tightening voting rules. These changes range from strict requirements for photo IDs to cutbacks in the time allowed for early voting to the winnowing of presumed nonvoters from the rolls and other general registration restrictions. Since the 2010 midterms, at least 25 states have enacted tougher ballot laws, according to the Brennan Center.

Some of these changes, in basic form, garner widespread approval among voters. This is particularly true of photo ID. A 2016 Associated Press poll found that 79% of respondents favored requiring all voters to provide some form of photo identification.

Proponents frame many of the changes as a means to defend against fraud. But the days of deceased voters allegedly casting ballots in Illinois’ Cook County, and voter turnout in some Louisiana precincts reaching 120%, are long over. Documented cases of in-person fraud are “super rare,” says Dan Hopkins, a professor of political science at the University of Pennsylvania whose research focuses on elections and public opinion.

One 2014 study in an academic journal, Dr. Hopkins points out, concluded that in the U.S. voter impersonation – the fraud against which photo ID is meant to defend – is reported at about the same rate as instances of alleged abduction by extraterrestrials.

The problem, Dr. Hopkins notes, is America’s long and troubled history of denying racial minorities their right to vote. Today’s new restrictions are inevitably seen in that old context.

Take photo ID. Many Americans see that as an easy hurdle to surmount. Who doesn’t have a driver’s license or a passport or something like that?

Lots of people, actually. And they tend to be those on the edges of mainstream economic society. People of color, poorer people, both young and elderly, tend to be most affected by ID requirements.

The effects of the restrictions can also depend on the way they are set up. Dr. Anderson of Emory University uses the example of Alabama. In that state, you have to have a government-issued ID to vote – but a public housing ID doesn’t count. Seventy-one percent of public housing occupants in the state are African Americans. Also, Alabama has been closing Department of Motor Vehicle offices in black counties.

You create an obstacle, then you create an obstacle to the obstacle, says Dr. Anderson. “We believed we had overcome,” she says. “We haven’t.”

Dr. Anderson says that one of her goals when writing her 2018 book “One Person No Vote” was to counter the idea that many of the new voting restrictions are just reasonable responses to concerns about the integrity of America’s voting systems.

Poor people move often, so they miss the official postcards asking if they wish to remain on the voting rolls. Young people, students, and minorities disproportionately don’t vote regularly. After missing a few ballots, their names start to be crossed out as well.

Right now America isn’t a real democracy, Dr. Anderson says.

“We came close to being a democracy with the Voting Rights Act,” she says. “But the forces of white supremacy have kept fighting back.”

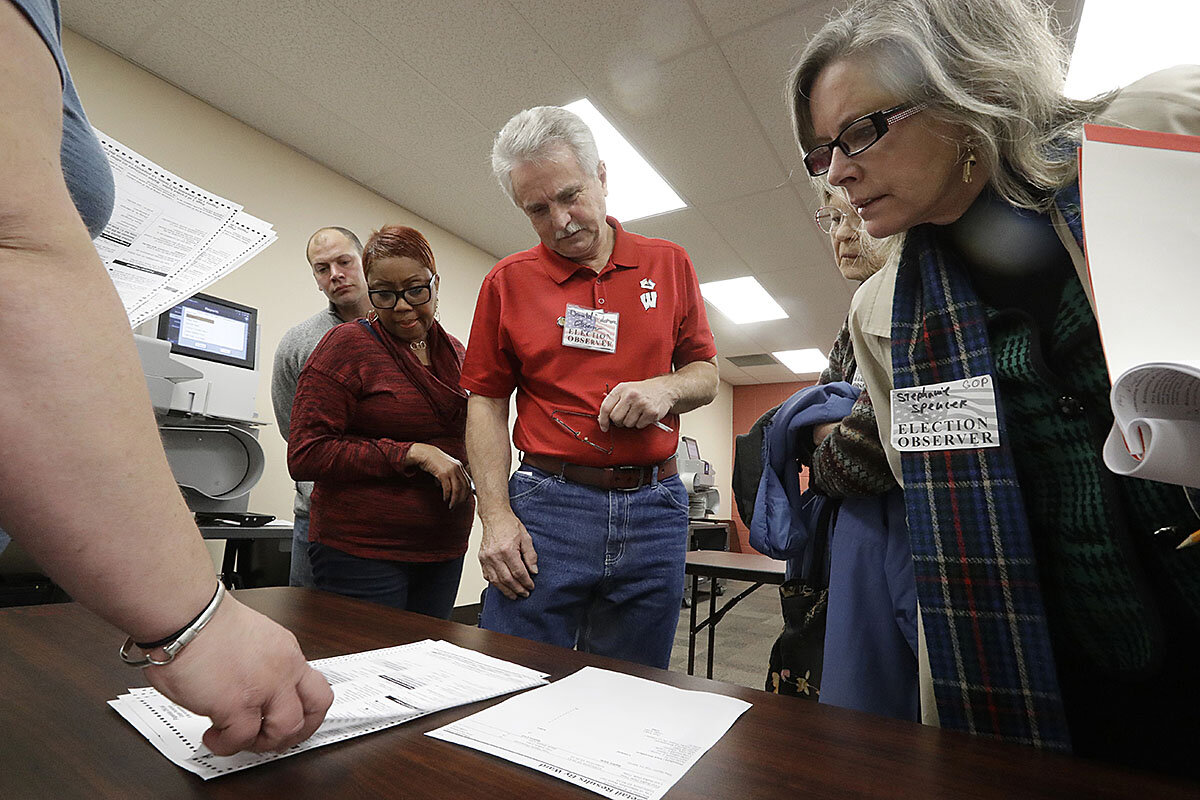

What happened in Wisconsin

Do voting restrictions actually affect elections? If so, how much?

Dr. Anderson and other fierce critics would certainly say yes. Their Exhibit A is the 2016 presidential election in Wisconsin. Wisconsin’s voter ID law, passed under GOP Gov. Scott Walker, requires all voters to present a driver’s license, state ID, passport, military ID, naturalization papers, or tribal ID to vote. (Other forms of ID are acceptable under certain circumstances.) Voters without proper identification can cast a provisional ballot, which will count if they present the document at a state office within 72 hours of the election.

In 2016, the first presidential election affected by the new law, there were 60,000 fewer votes for president than in 2012, says Dr. Anderson. Sixty-eight percent of the decline was in Milwaukee alone, a heavily Democratic and minority area.

Donald Trump won Wisconsin by roughly 20,000 votes. It was a harbinger of similarly close triumphs in other Rust Belt states that helped provide his margin of victory.

But many political scientists have a more nuanced view on the subject.

Evidence shows that photo ID requirements and other restrictions indeed prevent some voters from casting ballots or going to the polls in the first place, says Dr. Hopkins of the University of Pennsylvania. But studies also show that the magnitude of the effect is not great enough to actually sway many outcomes.

“This is an important issue of voter rights and civil rights. But the levels of disenfranchisement we have seen do not indicate any election we can point to that would have been shifted,” says Dr. Hopkins.

Take Wisconsin. It’s true minority turnout dropped in 2016 relative to 2012. But was that due to voting restrictions, or the fact that Barack Obama, the nation’s first African American president, wasn’t on the ballot? How did party mobilization efforts compare for those years? Could there have been some other factor?

Like many states, Wisconsin also has something of a split personality on voting issues. Under a GOP-led state government, it tightened ID laws – but it also allows same-day voter registration.

The way restrictions are drawn up and implemented also matters a lot. What IDs count? The question of whether a student ID is acceptable makes a big difference in heavily collegiate states such as New Hampshire and Wisconsin.

In the short run, new restrictions can sometimes even boost turnout. Studies have shown that they can produce a powerful emotional response among Democrats in general and affected groups in particular, spurring a counter-mobilization that actually leads to higher turnout at the polls. That response might eventually wear off – but long-term effects are difficult to predict. Older voters tend to skew Republican, and as they age they become statistically less likely to have driver’s licenses, passports, or other IDs.

Nevertheless, the partisan intent seems clear. It is Republican governors and legislators who are pushing for and implementing new restrictions. In 2012, Pennsylvania’s Republican state House leaders said publicly that the state’s new voter ID law would “allow” GOP candidate Mitt Romney to take the state. (A state judge later threw out the law as contrary to Pennsylvania’s Constitution.)

President Trump has called for a nationwide photo ID requirement, saying it would ensure only U.S. citizens vote in U.S. elections. (Multiple nationwide studies have found only a handful of documented cases of noncitizen votes.)

“There are sometimes clear political motivations [for instituting voting restrictions],” says Dr. Hopkins.

The disengagement factor

But voter photo ID, “purges” of infrequent voters from the rolls, and other moves are not the only things affecting the voting rates of minorities. At a time when America is rapidly becoming more diverse, it is voters’ own disengagement that may be most slowing the rise of the “transformative” coalition, and maintaining the clout of the “restorative” counterpart.

“It is this broader story of encouraging people to participate that’s the issue,” says Bernard Fraga, assistant professor of political science at Indiana University and author of “The Turnout Gap: Race, Ethnicity, and Political Inequality in a Diversifying America.”

The U.S. has long lagged on turnout compared with other developed nations. In part, this is because registration to vote in the U.S. has traditionally been an individual responsibility. Other nations may vote on weekends, or holidays. According to Pew Research data, 24 nations make voting compulsory, including the perennial top turnout nation, Belgium, which averages close to a 90% turnout.

In U.S. presidential elections, about 50% to 60% of eligible voting-age citizens typically turn out to vote. Midterms attract a turnout of about 40%, while local elections draw even less. Municipal primaries may be decided by as little as 15% of those eligible to vote.

Turnout of minority groups in America is particularly low. Whether it is the barrier of an ID, or simply apathy – a decision to not decide on political choices – minority turnout lags far behind that of white people, says Dr. Fraga.

In 2016, 65.3% of eligible white people said they voted, according to Pew data. Forty-nine percent of black people said the same thing, representing a sharp decline from 2012’s record 66.6% turnout.

Latino turnout lagged behind at 47.6%, according to Pew. A greater number of eligible Latinos have not voted than voted in each presidential election since 1996.

Asian Americans historically do not break the 50% turnout barrier, either. In 2016, their voting percentage was 49.3.

Voter ID and other restrictive policies don’t explain this minority turnout gap, says Dr. Fraga. Some states that have implemented relatively tight laws actually have higher minority turnout numbers.

And the gap has clear electoral effects. If minority turnout had equaled white turnout, given that minorities are preponderantly Democratic, Hillary Clinton would have won the presidency in 2016 instead of being narrowly defeated. Democrats would have regained a majority in the Senate.

Interestingly, the turnout gap is much smaller in places where minority groups make up a larger share of the population. This may be due to the fact that African Americans or Latinos feel they have the power to affect outcomes in a way they do not in overwhelmingly white areas. Or it may be because political campaigns cater to them and target them more when they might make more of a difference.

“The broad conclusion is, this is a story about engagement, empowerment, and mobilization,” says Dr. Fraga.

A perfect storm

All of this – sweeping demographic change, voter ID, voter roll “purges,” minority turnout, plus cameo appearances by partisan gerrymandering and the Electoral College – may roll into the electoral storm of the century in 18 months.

That’s because the 2020 presidential election is coming.

The 2018 midterms saw a huge spike in voter interest and turnout. As Dr. Hopkins pointed out in his 2018 book “The Increasingly United States: How and Why American Political Behavior Nationalized,” the old saying that “all politics is local” has now been turned on its head. All politics is now national, focused on the big stories from Washington via social media and nationalized media. Midterm interest was driven by anger toward and defense of President Trump. With the president himself on the ballot next fall, turnout could be off the charts.

It will be a great clash between the transformative coalition of anti-Trump Democrats and the restorative coalition of the pro-Trump base. A recent Fox News poll found that the percentage of voters who say today that they are “extremely” interested in the 2020 presidential election is already higher than the percentage who said the same thing on the day before the 2016 vote.

Michael McDonald, an election specialist at the University of Florida, is predicting record participation levels. “We are likely in for a storm of the century,” he recently tweeted, “with turnout levels not seen for a presidential election in the past 100 years.”