In clash over clearances, questions about long-term effects

Loading...

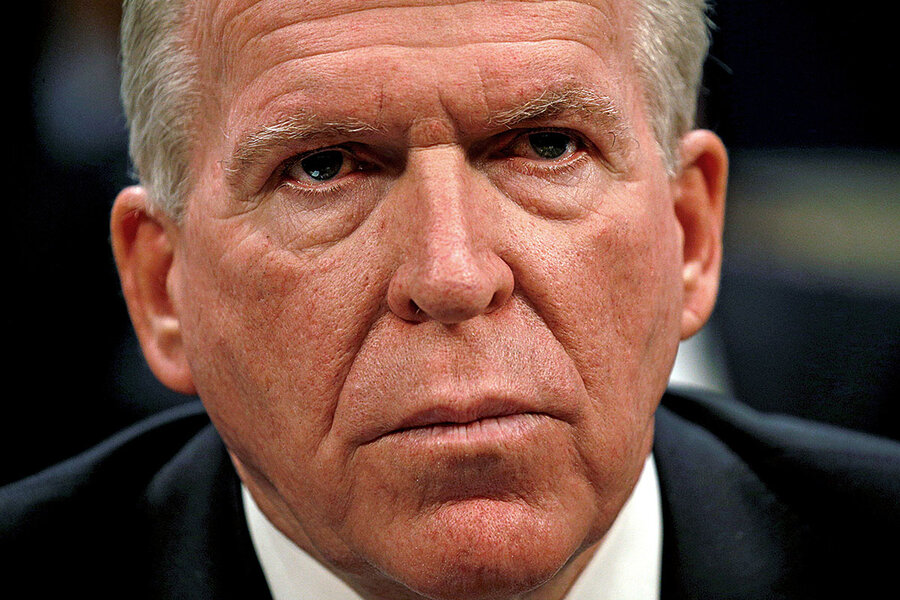

Can President Trump do that? Can he really personally revoke former CIA Director John Brennan’s security clearance, with a stroke of a pen?

Yes, he probably can. At least in the short term. His Article II constitutional powers regarding national security make him theoretically the top arbiter of United States secrets – who gets them, who doesn’t, and what they are.

The question is whether the action will cause that power to be circumscribed in the long term. No president has ever done anything like this before, say clearance experts. And in turning this particular dial of presidential power to “11,” he may push Congress and the courts to reexamine precedents and think of ways to curtail its use in the future.

Why We Wrote This

Country over party has, for the most part, been a bulwark for the intelligence community. In a crisis, such loyalty is paramount. Today, mutual recrimination is testing that imperative as never before.

“It just seems dangerous to our institutions that the president would just . . . strip someone of their security clearances because he doesn’t like what they have to say,” says Barbara McQuade, a University of Michigan law professor who was US Attorney for the Eastern District of Michigan from 2010 to 2017.

On Monday, Mr. Trump and his allies appeared energized by the Brennan controversy. Trump tweeted that he would welcome a threatened lawsuit from Mr. Brennan, and taunted his adversary as the “worst CIA director in our country’s history.”

At the same time, former CIA officials and other top security officials clamored to sign on to protest lists registering their opposition to something they said was undertaking purely in retaliation for Brennan’s criticisms of Trump. Ret. Adm. William McRaven, who led the raid that killed Osama bin Laden, was among the first to speak out, in a Washington Post opinion piece headlined, “Revoke my security clearance, too, Mr. President.”

Signees said that not all agreed with Brennan’s words. But the latest version of the protest letter on Monday said the signatures do represent “our firm belief that the country will be weakened if there is a political litmus test applied before seasoned experts are allowed to share their views.”

The outcome of a Brennan lawsuit would likely be difficult to predict. The former intelligence official would be better off to challenge the decision on Fifth Amendment due process grounds than on First Amendment free speech grounds, according to Bradley Moss, an attorney who specializes in clearance cases. Virtually all clearance revocations are carried out by procedures, list reasons for the action, and allow for appeal.

“These types of national security determinations are supposed to be above party,” Mr. Moss said on a podcast hosted by the national security blog Lawfare over the weekend.

Other experts said it would be possible for Brennan to win such a suit, but it would be an “uphill climb,” in the words of Brookings Institution expert Norman Eisen.

The courts are extremely reluctant to question the substance of executive branch national security decisions. But this singular move, aimed at a political critic, could push judges to set limits on presidential decisionmaking authority in this area, according to Mr. Eisen.

And if courts – or Congress – push back with such limits, Trump’s move would have produced an unintended effect. By using power to its limit, he would have limited that power, via reaction. An analogy might be the 22nd Amendment, limiting presidents to two terms. Ratified in 1951, it was a reaction against Franklin Delano Roosevelt, who ran and ran and ran, winning four terms.

One other long-term effect of the Brennan uproar might be the politicization of intelligence agencies, or at least a growing tendency among voters to see the agencies as political actors.

That is clearly a motive on the part of the administration. Trump’s continued attacks on the FBI and his reluctance to admit that Russia interfered with the 2016 election appear meant to lessen the credibility of the intelligence community at large, and special counsel Robert Mueller in particular.

But as Harvard Law School professor Jack Goldsmith writes, “Trump and his allies are not the only culprits here.” In reaction to Trump, some officials somewhere in the government leaked information from National Security Agency electronic surveillance early in the administration to damage former National Security Advisor Michael Flynn. When former intelligence officials criticize Trump on television, they often use intemperate language – Brennan included.

These officials have every right to express their opinions, according to Professor Goldsmith. But it was not that long ago that ex-top intelligence officials did not appear on TV panels.

“I do think that the credibility of the intelligence community as neutral and trustworthy suffers as a result,” writes Goldsmith.