Why government leakers leak

Loading...

The government contractor felt the secretly copied information was explosive. Perhaps it would be the subject of important congressional hearings. But leaking it to the press might also result in something else – life in jail.

Is this about Reality Leigh Winner, the National Security Agency contractor charged this week with leaking a document on Russian hacking to The Intercept? Nope. Daniel Ellsberg, the ex-RAND employee who lit a ferocious national controversy on the Vietnam War by leaking the Pentagon Papers to the press in 1971.

Leaks have roiled Washington since long before President Trump took office. The current administration seems particularly prone to insider leaks about the internal politics of the White House. But there have been important, clandestine leaks of US secrets since the nation’s founding. They’ve annoyed lots of Oval Office residents. Mr. Trump is not alone.

What motivates the leakers? Perhaps that’s a key to understanding the persistence of the practice. From the outside, leakers sometimes seem a bit like rigid do-gooders.

That’s often not the full story, though: dig in a bit, and many are revealed as complicated people driven by personal, as well as ideological, factors. Understanding the motivations for leaking can provide important context for the sensitive information leakers divulge.

“It’s a mix,” says David Greenberg, a professor of history and journalism at Rutgers University, of leaker motivations. “Sometimes it’s a sense of doing good. Other times it’s a sense of helping themselves.”

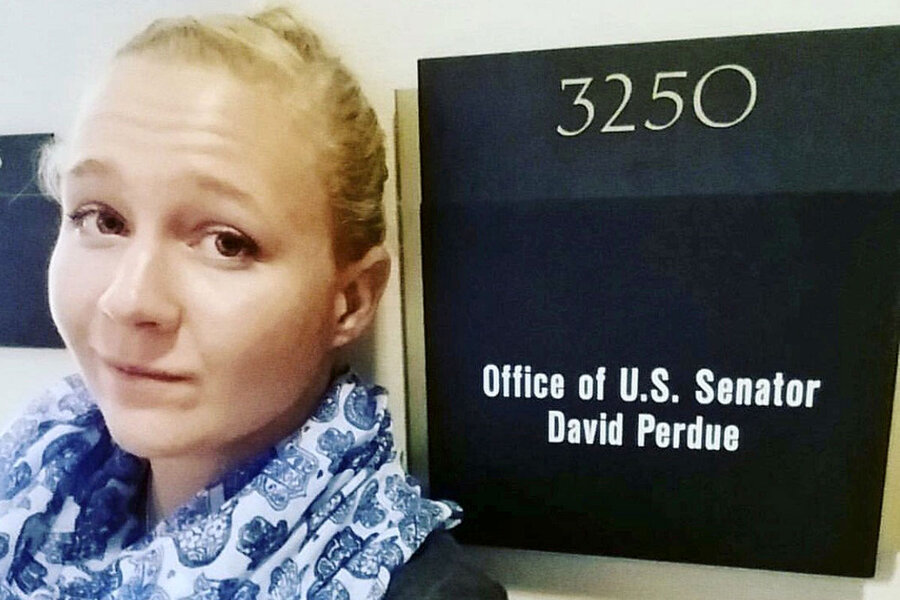

Right now little is known about Ms. Winner’s particular impulses. Winner, a Georgia resident, allegedly provided The Intercept – a publication established to report on material provided by ex-NSA contractor Edward Snowden – with a US document describing a Russian cyberattack on a US company that provides technical support to state voting agencies.

It’s possible Winner was driven by a dislike of Trump. Social-media accounts associated with her name express animosity toward the administration and its policies.

But that's an incomplete picture: The Texas-raised Winner is also an Air Force veteran who served her country as a gifted linguist.

“She’s a patriot, and to see her maligned and slandered in the media is very disheartening,” said her stepfather, Gary Davis, on CNN Tuesday.

Leakers face media's double-edged sword

It’s true the media can shine a harsh, distorting light on a leaker’s activities. It’s also true that without the media there wouldn’t be leaks at all.

Take Teddy Roosevelt. As perhaps the first president of the modern era, he started the US on the path to the powerful, centralized executive branch we know today. He leaked constantly to reporters, according to Prof. Greenberg, author of “Republic of Spin,” a history of presidential image management. TR was trying to control how he was portrayed in the press. He was astounded – and angry – when the press didn’t always shape the leaks in the way he wanted.

Then there was Edward M. House. A longtime key adviser to Woodrow Wilson, House was declining in influence when the end of World War I rolled around. At the Paris Peace Conference, House began leaking to US reporters as a means of regaining a role in the secret negotiations. Some journalists later wrote that strolling through the gardens of Paris in the company of House was the only way they could find out what was going on.

“Those who find themselves blocked on the inside turn to reporters. It’s a common dynamic in politics,” says Greenberg.

Jail time is rare

It’s also a dynamic that’s quite visible today. In the Trump White House, with its competing factions, advisers leak to reveal and influence the process. That’s why there are so many insider stories about who is up and who may be on the way out – and what upcoming executive orders Trump may sign.

In a larger sense, this is just how the government works. At all levels, from the West Wing to Capitol Hill to the lower levels of executive branch departments, leaks are a means of internal communication. Washington might grind to a halt without them.

“As a matter of reality there are leaks every day on all sorts of subjects. Some come from the top. They are part of the way the government functions,” says Mary-Rose Papandrea, a law professor and associate dean for academic affairs at the University of North Carolina School of Law in Chapel Hill.

Leaks of classified information are illegal. But for most of US history the number of leak prosecutions has been relatively small, given the number of leaks that occur, says Prof. Papandrea, who has written extensively about government secrecy and national security leaks.

That number began to rise under the Obama administration. With Winner, the Trump administration now has its first leak case. Will there be more? Trump’s harsh rhetoric about leaks seems to indicate that might be the case.

“The looming question is, what is the Department of Justice under Attorney General Sessions going to do?” says Papandrea.

Are leaks justifiable?

Another question that might be apropos is, are there good leaks and bad leaks? In other words, are there leaks where the information is important enough, and the public interest is enough at stake, to justify the action?

That is what Ellsberg believed, and what drove him to copy thousands of pages of the Pentagon Papers, a secret government report on the history of the involvement of the US in Vietnam. In one of the most famous acts of classified leaking in US history, Ellsberg passed this information on to The New York Times.

After the Times began publishing articles on the Pentagon Papers in June 1971, the Nixon administration won an injunction in federal court forcing cessation of publication. Ellsberg then gave The Washington Post its own copy of the papers. On June 30, the Supreme Court voted 6 to 3 that the government had not met the heavy burden of proof of injury required to restrain the press prior to publication.

“Only a free and unrestrained press can effectively expose deception in government,” wrote Justice Hugo Black for the majority.

Ironically, Ellsberg had not meant to facilitate a historic leap for freedom of the press. He had mostly hoped to spark congressional hearings on Vietnam. Those didn’t happen. He’d also thought the Pentagon Papers would cause the public to heap blame on the Democratic presidents who preceded Nixon for dragging the US into the mess. That didn’t happen either.

He also thought he would face a heavy penalty.

“You know, 7,000 pages, I’ll go for life,” Ellsberg said in an oral history recorded for the Nixon Library in 2008. “I thought this won’t be a year or two or five years. I expected to go to jail.”

That didn’t happen either. The government case against him was dismissed after the exposure of illegal White House efforts against him, such as an attempt to break into his psychiatrist’s office.

The other famous leaker of the Nixon era was “Deep Throat.” A source for Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein of The Washington Post, he was immortalized as the man who met reporters in a dark parking garage and told them to “follow the money.”

In reality, “Deep Throat,” revealed shortly before his death as FBI associate director Mark Felt, was motivated by more than altruism. He was also piqued. Nixon had passed him over when picking a new FBI chief following the death of J. Edgar Hoover. Felt thought he had deserved the job.

“There are a huge range of motivations for people to leak, from admirable, to somewhat less than admirable,” says Papandrea of the University of North Carolina School of Law.