From caricature to man of character: How time and art change image of Bush

Loading...

| NEW YORK

Last July, when former President George W. Bush began to smile and sway to “The Battle Hymn of the Republic,” holding hands with both his wife and former first lady Michelle Obama during the closing moments of a memorial service for five Dallas police officers, many of his long-time detractors could only look and mock.

Along with his ebullient, hand-pumping sway, many criticized the color of his suit, royal blue, in contrast with the somber black that most others, women and men, wore for the service, just days after the officers were killed.

On traditional and social media, Mr. Bush, making a rare public appearance at the time, was once again the president of the malaprop, seemingly lacking in seriousness and curiosity, the smirking architect of a disastrous and unnecessary war.

That caricature, however, is beginning to change.

Even for some on the left who once decried his character as well as his policies, the former Republican president’s reputation has been burnished during the early tumultuous weeks of fellow Republican Donald Trump’s presidency.

Many are looking back at Bush’s full-throated defense of Islam as a religion of peace in the immediate aftermath of 9/11, praising the 43rd president’s concern for America’s Muslim residents, as incidents of violence and prejudice today become more common.

Others, too, have found his current defense of the news media – a constitutionally mandated check meant “to hold power to account,” he recently said – as a critical conservative counterpoint to the current administration’s ongoing attacks.

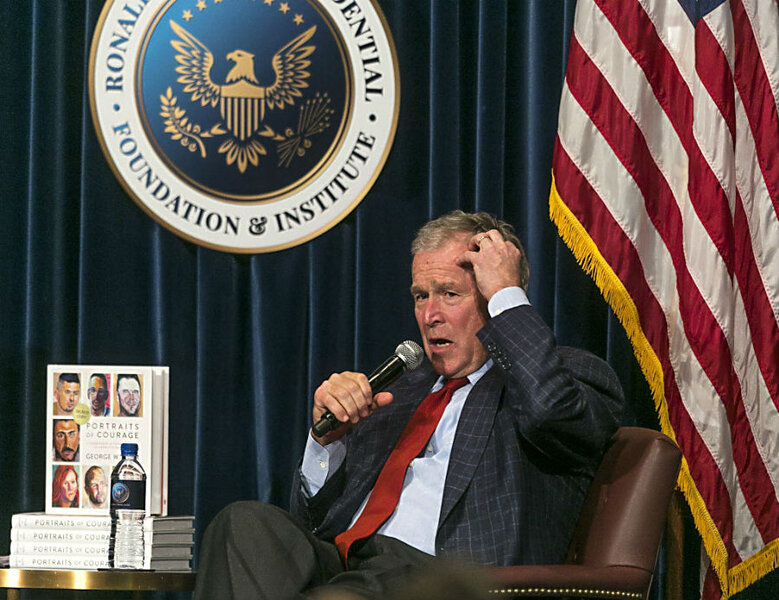

And with the release of his best-selling book of paintings, “Portraits of Courage: A Commander in Chief’s Tribute to America’s Warriors,” even highbrow critics at publications such as The New Yorker have begun to reassess the complexity and depth of Bush’s character.

The famous left-leaning magazine described the quality of the novice painter’s work as “astonishingly high.” His 98 portraits of wounded veterans from the Afghanistan and Iraq wars, wrote Peter Schjeldahl, the magazine’s long-time art critic, are “honestly observed and persuasively alive.”

This reporter, too, present at that Dallas memorial service last year, was struck by the singular emotion expressed by the swaying former president, as he nearly step-marched to the famously militaristic hymn.

Though startling, it felt appropriate – hopeful and full of a forward-looking optimism, a war-time president moved by the organ and the choir, feeling the emotion of the moment in a way others were not:

With a glory in His bosom that transfigures you and me,

As He died to make men holy, let us die to make men free!

Critics like Mr. Schjeldahl also have used religious terms, perhaps tellingly, to assess the former president’s work: “Painted atonements,” he called them.

The New York Times, too, titled its assessment by Mimi Swartz “ ‘W.’ and the Art of Redemption.”

“Mr. Bush discovered what many who paint discover: that as he worked on their portraits, he came to understand his sitters, and their pain, as well as their love for one another,” wrote Ms. Swartz, also the executive editor at Texas Monthly.

While Bush’s sensitive and expressive paintings of wounded veterans might invite reflections on the artist’s inner life, such terms might also reflect the posture of the critics, whose generally positive assessments seem to imply a kind of impulse to forgive.

At the same time, however, as the former president made the rounds to promote his book, reemerging in public life after keeping a low profile during the Obama years, he has done some forgiving of his own. He’s laughed off Will Ferrell's mocking impression of his malapropisms, saying it never bothered him – in stark contrast with Mr. Trump, who has clearly been irked by Alec Baldwin’s impression of him.

Though Bush admits he struggled at times with the way he was portrayed in the media, he’s been outspoken about the “indispensable” role of the press in American democracy – another stark contrast with Trump, though he says that is not his intention.

“I spoke about the free press and people said, ‘You are criticizing President Trump.' That's not the case at all," the former president told Voice of America this month. “I am a believer in the Constitution, which talks about freedom of religion, freedom of the press, and I'm a defender of that. I fully understood that power can be addictive and power can be corrosive, and so an independent voice holds people like me in check and so I think it's very important."

Historical pattern

Scholars point out, however, that most presidents see their reputations and the public approval ratings rise after they leave office, and it should be no surprise that even among liberals, Bush is being assessed more generously today.

“It's a typical public opinion pattern that ex-presidents become more popular once they are out of office,” says Patrick Miller, professor of political science at the University of Kansas in Lawrence, who studies American politics and attitudes of partisanship. “The constant criticism is gone, and people begin to forget many of their reasons for disliking the person.”

Such short memories, too, belie how intensely the left felt about Bush when he left office, says David O’Connell, professor of political science at Dickinson College in Pennsylvania and author of “God Wills It: Presidents and the Political Use of Religion.”

“The recent expressions of admiration for former President Bush are quite amusing,” says Professor O’Connell. “Because the truth is that Bush's reelection in 2004 was met with much of the same apocalyptic dismay as Trump's victory was this past November.”

“Liberals were concerned about infringements of civil rights and civil liberties, about a widening war on terror that had no end in sight, and about Bush's campaign promises to amend the Constitution to ban same-sex marriage,” he continues. “Talk of how Bush might be impeached was common, and the left regularly tried to link Bush to Nazi fascism. That all sounds very familiar to me.”

Scholars point out that presidents such as Herbert Hoover were also “massively unpopular” when they left office. Blamed for the Great Depression, he rehabilitated his reputation by devoting himself to charitable work, becoming chairman of the Boys Club of America and founding a research institute at Stanford University in California.

Former President Bill Clinton, too, a Democrat, eulogized disgraced Republican President Richard Nixon, saying the days of judging him on Watergate alone were over. “Most presidents, after leaving office, are rated higher than when they were in office,” notes Jack Johannes, political science professor at Villanova University, outside Philadelphia.

“Recent cases would include Truman and Eisenhower, and probably Bill Clinton and Jimmy Carter as well,” he continues. “Bush is receiving that same treatment. Voters’ memories are short and political time moves rapidly. I doubt if the art has any effect other than to reveal a ‘softer side’ of George W. Bush.”

'Heavy burden to bear'

Yet some liberal-leaning scholars note the impact that Bush’s war-time decisions may have had on him – a burden reflected, perhaps, in the president-turned-successful-artist’s work.

“For George Bush, when you greet those planes back from abroad, with flags draped over the coffins, and you meet with the families – I think he does recognize that that’s on him in some ways, and that’s a heavy burden to bear,” says Christina Greer, professor of political science at Fordham University in New York, who studies black ethnic politics and the role of public opinion in campaigns and elections.

“Because of your actions to protect the larger country, there are Americans who sacrificed their lives for that,” she continues. “I think Bush painting these veterans – I’m not a psychologist, but this might be his way of processing what happened under his watch.”

Bush has refrained from directly criticizing either Obama or Trump, saying it doesn’t serve the presidency well to have a former president second-guessing their own difficult decisions – though they haven’t sought his counsel, either.

"Neither of my successors asked and that's fine,” Bush told Voice of America. “Doesn't hurt my feelings at all. I'm just a sensitive artist now, painting."