Trump: Not first wealthy president, but unique conflicts of interest

Loading...

When Donald Trump enters the Oval Office on Jan. 21 he may bring with him the greatest potential for business and financial conflicts of interest of any US president, ever.

That’s not just because he’s wealthy. Yes, Mr. Trump boasts that he’s a billionaire, but many other White House occupants have been very rich.

It’s not just because he employs his kids. Other presidents have had family connection issues.

It’s the combination of those things, added to a third: Trump’s a dealmaker who’s still dealing. Other presidents have had extensive land holdings or been the beneficiary of established family fortunes. The nation’s 45th chief executive is still out there in the marketplace at the moment.

“What’s really new about this is with Trump you’ve got a figure who had been an active businessman for his entire career really, up to his victory, in a way no president previously has,” says Guian McKee, an historian and associate professor at the University of Virginia’s Miller Center of Public Affairs.

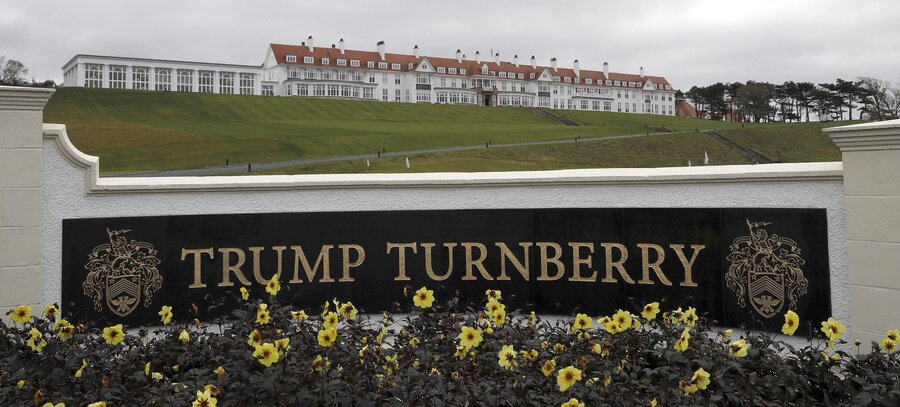

A quick look at numbers shows the scale of the problem. Donald Trump has at least 500 businesses – hotels, casinos, golf courses and brand deals stretching from Azerbaijan to Ireland. He’s borrowed a lot to amass this empire, and currently owes banks and other lenders an estimated $650 million. Like many tycoons he’s involved in litigation: he just settled a big fraud case against Trump University, but he still has at least 74 lawsuits wending their way through the courts.

It’s the international aspect of his empire that might pose the biggest conundrums. For instance, Trump’s formed eight companies in Saudi Arabia since the beginning of his campaign, according to a new report in the Washington Post. All are apparently linked to a hotel project.

Business and politics in Saudi Arabia are famously intertwined, as a small group of elite figures control both. Does this mean Riyadh now has a new lever with which to nudge Washington in its desired direction?

In Turkey, Trump gets millions in licensing cash from an Istanbul luxury building that bears his name. Its owner has been increasingly outspoken in supporting the country’s president, Recep Tayyip Erdogan, as he cracks down on domestic dissent in the wake of a failed coup.

Trump himself acknowledged that he has “a little conflict of interest” in Turkey in an interview on Stephen Bannon’s Breitbart News radio show taped prior to his presidential run.

Back in the United States, foreign diplomats are already flocking to book rooms and hold events at Trump’s new hotel on Pennsylvania Avenue. To do otherwise, they say, might be seen as a sign of disrespect.

Trump’s family offers further complications. His daughter Ivanka wore a $10,800 bangle from her own jewelry line during an interview with her father on “60 Minutes.” A publicist announced this to the world via social media; later, the president of the Ivanka Trump fashion brand apologized for what seemed an attempt to profit from her father’s new position.

Ivanka’s husband, Jared Kushner, has a brother who owns a $3 billion health insurance firm that is deeply involved in the Obamacare market. How might Trump’s repeal-and-replace promise for the Affordable Care Act affect it?

Trump’s answer to all these conflict questions is simple: he’ll put his businesses in a “blind trust” run by his kids. That way he’ll be able to focus on the public’s business.

But that’s not enough, say many experts on legal and governmental transparency.

According to a Congressional Research Service report, “the public officer will be shielded from knowledge of the identity of the specific assets in the trust" through sales and new acquisitions. "Without such knowledge, conflict of interest issues would be avoided because no particular asset in the trust could act as an influence upon the official duties that the officer performs for the Government.”

The sort of trust Trump is proposing couldn’t be truly blind, since he well knows what his assets are and family members are unlikely to be truly independent.

They say the best solution is for Trump to liquidate his holdings and put the money in a true blind trust run by non-family executives. That’s what the Wall Street Journal called for in an editorial last Friday. An open letter from Common Cause, Public Citizen, the Sunlight Foundation, and other DC good government groups makes the same point.

“We understand that this arrangement would require you to sever your relationship with the businesses that bear your name and with which you have invested a life’s work. But whatever the personal discomfort caused, there is no acceptable alternative,” says the letter.

Past presidents just haven’t faced the same level of complications that Trump’s holdings produce.

Early US chief executives were rich, fabulously so if inflation is taken into account. George Washington was worth over $500 million by today’s measures. Thomas Jefferson was worth over $200 million. But that wealth was in land, and slaves. The scope of the presidency was more limited and the opportunity for personal benefit smaller.

In general the corruption problems of the late 19th and early 20th century presidencies were centered on aides and sycophants. The Teapot Dome oil lands scandal of the 1920s, for instance, sullied President Warren G. Harding’s reputation. But the dollars ended up in the pockets of hangers-on, not him.

Many wealthy presidents have been heirs. Theodore and Franklin Roosevelt both lived in comfort thanks to the work of their ancestors. John F. Kennedy’s father Joseph Kennedy earned his family’s fortune as a stock picker, businessman, and movie producer, among other things. But JFK himself lived off the proceeds of a $10 million trust fund well into his presidency, according to author Richard Reeves. As a birthday present in 1962, Kennedy received $3 million of the fund principal.

Lyndon Baines Johnson pioneered the presidential use of a blind trust. When he rose to the Oval Office following Kennedy’s assassination, LBJ placed his holdings, primarily radio and TV stations in the Austin area, in the hands of nominally independent trustees.

Throughout his presidency, Johnson and his aides insisted that he had divorced himself completely from his business interests. This was untrue, according to biographer Robert Caro. LBJ spoke frequently with Texas Appeals Court Judge Anton Moursund, a member of his inner circle and the primary trustee. He also spoke frequently with his station general manager. Johnson installed in the White House residence special phone lines routed around government operators to conduct these calls.

“All during his presidency, the phones stayed in place, and the calls went on,” Mr. Caro writes in the fourth volume of his LBJ opus, “The Passage of Power.”

What will Trump do? As president, he is exempt from legislation that covers possible conflicts of interest for lower-ranking officials. There is some question as to whether he will be covered by the emoluments clause of the Constitution, which prohibits US officeholders from receiving any presents of value from foreign powers. But the clause does not specifically name the president, so some constitutional scholars think it may not apply.

In terms of maintaining public confidence, this issue might be trickier for Trump to handle than he thinks.

“It has the potential to do real damage to Trump’s presidency,” says Dr. McKee of the Miller Center. “It could be a constant drumbeat.”

The norm would be for Trump to liquidate his holdings and then live off financial instruments, as others have done. But Trump got elected despite breaking many political norms that members of the press and political scientists thought were immutable. This might be another one. He’s said what he’s going to do, and he could well stick with it, ignoring all the “conflict of interest” cries.

“The other possibility is that his supporters are so keyed in that they just see this as, ‘Of course he’s doing this.’ It’s part of what they liked about him to begin with,” says McKee.