How early voting has become so politicized this election

Loading...

| Atlanta

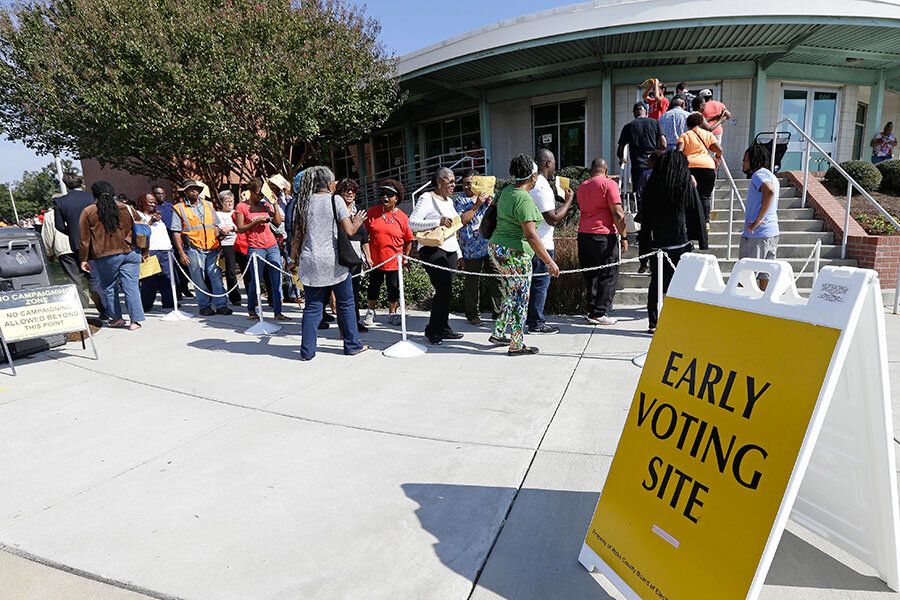

Early voting in North Carolina is raising questions about whether some Southern states are depressing Democratic turnout through new voter laws.

Democrats are three percentage points off their 2012 pace, while Republicans are up by nearly nine points. This comes after North Carolina’s Republican-led legislature passed new early voting rules in 2013 that limit the hours and places available for early voting.

In 2012, for example, Guilford County had 12 polling stations in the first week of early voting. This year, it had one. At one point, the number of voters in the county was off 85 percent compared with the same day in 2012.

The shifts in Democratic and Republican turnout could point to greater enthusiasm among Republicans than Democrats this election. But early voting has traditionally been popular among groups that lean Democratic, such as the poor and minorities, so the shift could also be a result of the new laws.

Nationwide, Republicans have been pushing to rein in early voting while Democrats have sought to expand it. But the fight is particularly acute in Southern states like North Carolina, which until 2013, could change their election laws only with Department of Justice approval.

Now, after that year’s landmark Supreme Court ruling, nine states and parts of six others are allowed to set their own course.

Pinpointing the effect of voting rule changes is “difficult, because we have multiple things going on here,” says Michael McDonald, a University of Florida election analyst.

Yet some experts say the data strongly suggest the laws are having an effect.

“You can’t argue with pure numbers and the impact that decisions like locations, days, and hours have on voters, two-thirds of whom may vote before Nov. 8,” says Michael Bitzer, a political scientist at Catawba College.

Overall, Democrats in North Carolina are still voting early in greater numbers than Republicans. And some polling locations have seen record turnouts in the curtailed early voting period, suggesting that the ultimate effect may not be as substantial as some suggest.

But North Carolina is a useful window into the issue. The state’s attempts to recast voter laws have at times run afoul of federal courts. A law requiring voter IDs was written to “target African Americans with almost surgical precision,” according to a three-judge panel of United States Fourth Circuit Court of Appeals, which struck it down.

North Carolina’s new rules on early voting cut off a week of voting and nix Saturdays and Sundays, which had been key to Democrats’ “souls to polls” get-out-the-vote strategy in 2008, when Barack Obama won the state. The Fourth Circuit restored the 2012 early voting period, but allowed counties to adjust hours and voting locations, largely because of the short notice between the ruling and the election.

“We will never discourage anyone from voting, but none of us have any obligation in any shape, form or fashion to do anything to help the Democrats win this election,” Republican First Congressional District Chairman Garry Terry wrote to local Republican election boards this summer. “Left unchecked, they would have early voting sites at every large gathering place for Democrats.”

Democratic strongholds like Charlotte have seen two dozen early polling places reduced to 10.

Overall, tougher voting rules in North Carolina and other states are suppressing the minority vote by three to four percentage points, Professor McDonald says, citing several studies, including one by the US Government Accountability Office.

The risks are steep for Republicans. Though the Supreme Court vacated preclearance requirements for states like North Carolina, federal courts can still place jurisdictions under federal oversight if there’s evidence of disenfranchisement.

But there are signs that, in some instances, people in North Carolina are adapting to the new rules.

In Guilford, as more polling places have opened, the African-American vote has rebounded and may in the end surpass 2012. And statewide, the biggest change in early voting this year is the 40 percent rise of early voters unaffiliated with either party. So far, many of those unaffiliated voters have been young people and women – traditionally Democratic voting blocs. Less-educated white men – Donald Trump’s chief demographic – are voting in only slightly higher numbers than in 2012.

What’s important ultimately “is the infrastructure of voting, but it’s also the campaign strategy,” says Professor Bitzer. “How campaigns react to changes in the rules of the game is just as important as the actual rules of the game.”