The Politics of US series: The shrinking middle class

Loading...

Follow us on Twitter @CSM_politics. Review the previous installment on guns, here.

In this week's edition:

- Cover story: The town the future forgot

- Update: At last, hope that the US economy has turned a corner

- By the numbers: What's happening to the middle class – in one chart

- Civics 101: Taxing the rich

- The candidates: Where they stand on income issues

- Interview: Author J.D. Vance on America's hillbilly rebellion

- Engage: Join in on a civil conversation, start discussions in your classroom, and see perspectives from different sides.

- Our picks: "Debate: Is there too much income inequality in America?" – and more

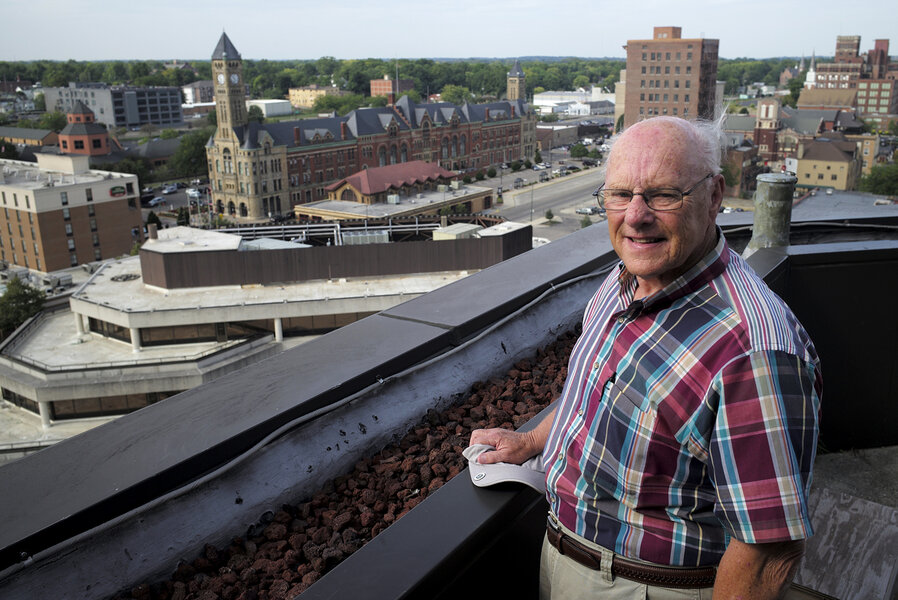

The town the future forgot

By Jeremy Borden / Contributor

A faded “Springfield A Great Place to Live” sign greets those entering this Ohio city of 59,000, at the heart of which looms the Crowell-Collier publishing plant – an empty monument to a once-thriving middle class.

This is a town of Dick Hatfields, who remember cruising around a crowded town in a '53 Chevrolet. Who can point to where the old root beer stand used to be. Who recount the time when Duke Ellington came to town.

Those things are now gone. Indeed, between 2000 and 2014, Springfield saw more of its middle class slip down the economic ladder than any other metro area in the United States, tying Goldsboro, N.C.

Yet Springfield is also a town of Kevin Roses, bounding 30-somethings who look at underutilized Victorian buildings just beyond the Crowell plant and see opportunity.

Yes, Springfield might not be the "Champion City" it once was, but in that history are the seeds of a renaissance. The promise of that future is right there, if only the city would grab it.

Those two competing worldviews have played out across the country, as pressures on the American middle class have refracted politics. Trump is one manifestation. But much deeper is the concern that, for many, the future has already closed in front of them – and Washington seems chronically unable to stop it.

Read more

• • •

UPDATE: With new Census data released Tuesday, there is hope that US economy might be finally turning a corner for everyone. Median household income rose by 5.2 percent from 2014 to 2015 – the first increase since 2007. The growth was even more robust for the lowest earners. Read the story here.

• • •

BY THE NUMBERS

• • •

CIVICS 101: How America's approach to taxing the rich has changed

By Laurent Belsie, Staff writer

Americans paid no federal income tax for the first eight decades of the republic. Congress instituted a temporary one to pay Civil War debts, but when it enacted a second one in 1894, the US Supreme Court famously ruled it unconstitutional.

It wasn't until 1913, when Democrats and progressive Republicans came together to pass the 16th Amendment, that the constitutional objections to direct federal taxation were cleared away and the modern system began to take shape.

The tax rates started small – the top rate was 7 percent – but the costs of World War I quickly pushed it to 77 percent. Ever since, the top rate has followed a predictable pattern: high in times of major wars and the Great Depression, low (or at least falling) the rest of the time. (See chart.)

Something else has changed, too. The federal government has become extremely reliant on the income tax on individuals, which has accounted for nearly half of its revenue since World War II.

Federal income taxes have almost always been progressive: the rich pay a higher rate than the poor or the middle class. But the top tax rate tells only part of that story. It only applies to income over and above certain thresholds. Loopholes and exemptions and the interplay between corporate and individual income taxes make it even less likely that the rich pay that rate.

In 2014, Americans earning more than $250,000 paid an average 25.7 percent, according to the Pew Research Center, even though the official rate for those earners was anywhere from 33 percent to 39.6 percent.

Is the system fair? That question has riled American politics since the federal income tax came into being. In 2014, the rich (the $250,000-plus set) paid just over half of all federal individual income taxes, according to Pew, while those making less than $50,000 paid only 5.7 percent.

As evidence mounts that the very rich have reaped almost all the nation's economic gains since the Great Recession, reformers are pushing to impose a higher income tax rate on the rich. Others are eager to change the tax code (including the one on corporate taxes) so there are fewer loopholes. Still others want a higher estate tax so that income inequality isn't passed down from generation to generation.

Prospects for tax reform look dim, however, unless November's election shifts the balance of power decisively to one party or the other.

• • •

THE CANDIDATES: Where they stand on inequality issues

We encourage you to contact the Monitor on Twitter @csm_politics or by email csmpolitics@csps.com if you can improve our chart!

Sources: the Jill Stein campaign, the Clinton campaign website, the Trump campaign website, ProCon.org, the Stein campaign website, iSideWith.com, The Fiscal Times, On the Issues, The Hill, CNN Money, The Washington Post

• • •

INTERVIEW: J.D. Vance, author of 'Hillbilly Elegy'

J.D. Vance, author of the New York Times bestseller 'Hillbilly Elegy,' has seen America from both sides – as a Kentucky “hillbilly” turned United States Marine and as a graduate of Yale Law and a 30-something San Francisco financier. And he sees in “his” people a group that appears forgotten and ignored by the coastal liberal elite.

The Monitor's Patrik Jonsson recently interviewed Mr. Vance. His answers have been edited for clarity and brevity.

Q: Your grandparents were pioneers on the Hillbilly Highway, Route 23, that led out of the mountains to jobs in places like Middletown, Ohio, the home of Armco Steel. But much of the generation that you write about in your book has taken a different path. Talk about that.

My grandparents and members of their generation were very willing to move for opportunity, but data today tell us that we’re much less mobile now than we were 20 or 30 years ago. Part of it is definitely a reluctance to move to new opportunities. But it’s a story complicated by the fact that moving isn’t always a great thing, especially for those left behind when the brain drain sends the talent to Atlanta or Denver and those who are left are people really struggling to get by….

Hopefully, the lesson from 2016, when the dust clears, is a recognition that our politics can’t continue as usual, because if it does these problems only get worse.

Read more

• • •

ENGAGE: Living Room Conversations and AllSides.com

Discuss: Join a civil conversation

- Have a Living Room Conversation about the opportunity gap with half a dozen friends who have diverse opinions. Enjoy this simple, respectful, structured program that begins with human relationships.

- Create your own pro-con list for ways to address economic inequality while collaborating with others from the left, center and right. Engage with people and ideas from all sides of the issue using this online interactive tool.

Discover: Inequality means different things to different people

The words we use can shut down dialog because they mean different things to different people. Sometimes a seemingly innocent word will provoke an emotional reaction, or perhaps just a different idea of what it really means or connotes. Until we fully understand what a term means and implies to someone else, we don't know the issue and can't effectively communicate.

Check out different perceptions of inequality and inequity, equality, hard work, the American Dream, social responsibility and social justice, and the welfare system.

Schools: Evaluate and discuss in the classroom

Discuss inequality in the classroom using a specialized lesson plan that teaches respectful dialog, fostering mutual respect and understanding. This program can be easily integrated into current curriculum, and includes various guides and online tools for making the class activity more engaging and revealing.

• • •

OUR PICKS: Recommended reading and viewing

1. “Wealth inequality in America,” by pseudonymous filmmaker Politizane, based on Mother Jones charts

The bottom 40 percent of Americans barely have any of the wealth. It’s hard to even seen them on the chart. But the top 1 percent has more of the country’s wealth than 9 out of 10 Americans believe the entire top 20 percent should have. Mind-blowing.

2. "Debate: Is There Too Much Inequality in America?" From Learn Liberty, a project of the the Institute for Humane Studies at George Mason University

One of the most important questions for me is: How easy is it, or how difficult is it, for folks who start off poor, to no longer be poor after five years or 10 years or 15 years?

3. "Coming Apart: The State of White America, 1960-2010," by Charles Murray

‘The more opulent citizens take great care not to stand aloof from the people,’ wrote Alexis de Tocqueville, the great chronicler of American democracy, in the 1830s. ‘On the contrary, they constantly keep on easy terms with the lower classes: They listen to them, they speak to them every day.’ Americans love to see themselves this way. But there's a problem: It's not true anymore, and it has been progressively less true since the 1960s.... that problem is more pervasive than either political or economic inequality. What we now face is a problem of cultural inequality.

4. “In climbing income ladder, location matters,” New York Times interactive graphics based on study by Harvard's Economic Opportunity Project

The study — based on millions of anonymous earnings records and being released this week by a team of top academic economists — is the first with enough data to compare upward mobility across metropolitan areas. These comparisons provide some of the most powerful evidence so far about the factors that seem to drive people’s chances of rising beyond the station of their birth, including education, family structure and the economic layout of metropolitan areas.

5. "Evicted," A profile of destitute renters and their landlords in Milwaukee, by Harvard sociologist Matthew Desmond

The day Arleen and her boys had to be out was cold. But if she waited any longer, the landlord would summon the sheriff, who would arrive with a gun, a team of boot-footed movers, and a folder judge’s order saying that her house was no longer hers. She would be given two options: truck or curb. 'Truck' would mean that her things would be loaded into an eighteen-footer and later checked into bonded storage. She could get everything back after paying $350. Arleen didn’t have $350, so she would have opted for 'curb,' which would mean watching the movers pile everything onto the sidewalk. Her mattresses. A floor-model television. Her copy of 'Don’t Be Afraid to Discipline.' Her nice glass dining table and the lace tablecloth that fit just-so. Silk plants. Bibles. The meat cuts in the freezer. The shower curtain. [Her son] Jafaris’s asthma machine.

Read The Monitor's interview with author Matthew Desmond.

6. "Inequality for All," a documentary by Robert Reich

Remember: We make the rules of the economy. We have the power to change those rules. You’ve got to mobilize, you’ve got to organize, you’ve got to energize other people. Politics is not, ‘out there.’ It starts here.