The gender gap in American politics

Loading...

Hillary Clinton and Mary Thomas have little in common, except for this: They both hope to add to the meager ranks of America's female elected officials come January.

You know about Clinton, but probably not Thomas — a conservative Republican, opponent of abortion and Obamacare, former general counsel of Florida's Department of Elder Affairs. She's running in Florida's 2nd District to become the first Indian-American woman in Congress. It's no easy task.

"There is still a good ol' boys network that is in place," she says, though she insists that "A lot of people see the value in having different types of people in Washington."

Even as Clinton attempts to shatter what she has called "the highest, hardest glass ceiling," other women like Thomas are testing other, lower ceilings. There are many: Women in the U.S. remain significantly underrepresented at all levels of elected office.

"Historically, we have centuries of catching up to do," says Missy Shorey, executive director of the conservative-leaning Maggie's List, one of a number of groups supporting female candidates.

Though women are more than half of the American population, they now account for just a fifth of all U.S. representatives and senators, and one in four state lawmakers. They serve as governors of only six states and are mayors in roughly 19 percent of the nation's largest cities.

There has been progress; as recently as 1978, there were no women U.S. senators, and now there are 20. Still, there has been little headway since a surge of women won office in the 1980s and early 1990s. Sixteen states have fewer women serving in legislatures than in 2005, and five others have shown no improvement, according to an analysis by The Associated Press of data collected by the National Conference of State Legislatures.

It is another aspect of the gender divide — one of the most glaring in our society. Women still earn 79 cents for every dollar men take home; men outnumber women in higher paying occupations, though even there they are often paid less. And the division plays out politically, as well. Women have tended to vote with the Democrats more often; polls have shown Clinton with a double-digit lead over Donald Trump among women, and Trump leading Clinton by double digits among men.

As the Associated Press reported, Elizabeth Andrus, a registered Republican from Delaware, Ohio, sees "buffoonery" in the Republican nominee and says "I am not on the Trump train." With all the trouble in the world, she went on, "you just don't want Donald Trump as president."

Her negative impression of Trump was shared by most of the dozens of white, suburban women from politically important states who were interviewed by The Associated Press this spring. Their views are reflected in opinion polls, such as a recent AP-GfK survey that found 70 percent of women have unfavorable opinions of Trump.

Advocates say the dearth of women officeholders has had consequences. They say women's voices have been muted in local, state and national discussions of all issues, from climate change to foreign policy, but particularly of concerns important to women and working mothers: family leave, child care and equal pay, for example. They point to instances where women in office have made a difference.

Kim McMillan was first elected as a Democrat to her seat in Tennessee's House of Representatives in 1994 when she was 32 years old, a working mother of two children under the age of 3. She was motivated to run after visiting the state Capitol as part of her law practice.

"I went up to the gallery upstairs and you could look out at the entire House of Representatives. I remember standing up there and looking at the House floor, and I didn't see anybody who looked like me," McMillan says. "There were no women that I could see."

More than once, she was told she couldn't win because she was a woman. She recalls being asked why she would run with two young children to care for.

McMillan won that race and eventually served six terms, rising to become the first woman majority leader. A major accomplishment: expansion of pre-kindergarten education around the state.

"I felt like I represented people who didn't have any representation, working mothers like me," says McMillan, who now serves as the first female mayor of Clarksville, the fifth largest city in Tennessee.

Whether a Clinton win in November will inspire a new generation of female politicians remains to be seen. While the election of a woman as U.S. president would be unprecedented, at least 52 other countries around the world have had a female head of state in the last 50 years. Great Britain got its second female prime minister when Theresa May took office this month.

Female representation varies significantly around the U.S. Six states have never elected or appointed a woman to the U.S. House of Representatives, and 22 have never had a woman represent them in the U.S. Senate. Mississippi is the only state where a woman has never served as a congresswoman, U.S. senator or governor.

Colorado has the highest number of women serving in a state legislature, with 42 percent, but it has never had a woman governor or U.S. senator.

And while Nikki Haley is South Carolina's governor, the state has never sent a woman to the U.S. Senate and has one of the lowest percentages of female state lawmakers at 14 percent.

A major problem, activists say, is convincing women to run. Researchers say women generally need to be recruited to seek elected office, whereas men are more likely to decide on their own. Men are also the ones who are more likely to be recruited.

"We know that when women run for office, they win as often as men do," says Debbie Walsh, executive director of the Center for American Women and Politics at Rutgers University. "The number of women running isn't going up, and so the number of women in office isn't going up."

Quotas have been credited by some researchers with boosting the number of women in office in a few countries, but the political parties in the U.S. are unlikely to consider any such system. Instead, the work of recruiting and supporting women has largely fallen to outside groups such as EMILY's List.

Founded in 1985, the group backs Democrats who support abortion rights. It points to a record of helping elect 19 women to the U.S. Senate, 110 women to the U.S. House of Representatives and more than 700 women to state and local offices, including 11 governors.

It's not just financial support, although EMILY's List says it has raised more than $400 million since it was created. The group works to recruit female candidates, offering them training and guidance in such areas as hiring staff, developing a financial plan and honing campaign messages. It also offers a support network of elected officials who can mentor female candidates.

"No matter who you are, when running for office for the first time you have a lot of questions and need answers," says Marcy Stech, who oversees communications for EMILY's List. "We want to help them make sure those boxes are checked."

A support network has been instrumental throughout Ellen Rosenblum's career, beginning as a lawyer in Oregon and continuing as she was appointed a state court judge and later during her successful bid for state attorney general. Two of her early mentors were former Oregon Supreme Court Justice Betty Roberts, the first woman to serve on an Oregon appellate court, and Barbara Roberts, the first woman elected governor of Oregon.

Rosenblum says she worked to pay it forward, helping to build up a statewide group of women lawyers. When it came to deciding in late 2011 whether to launch her first bid for statewide office, that same network was instrumental.

"I needed lots and lots of advice," says Rosenblum, who at the time had just retired as a judge. "I needed women to talk to, to make sure I was not completely out of my mind to do this."

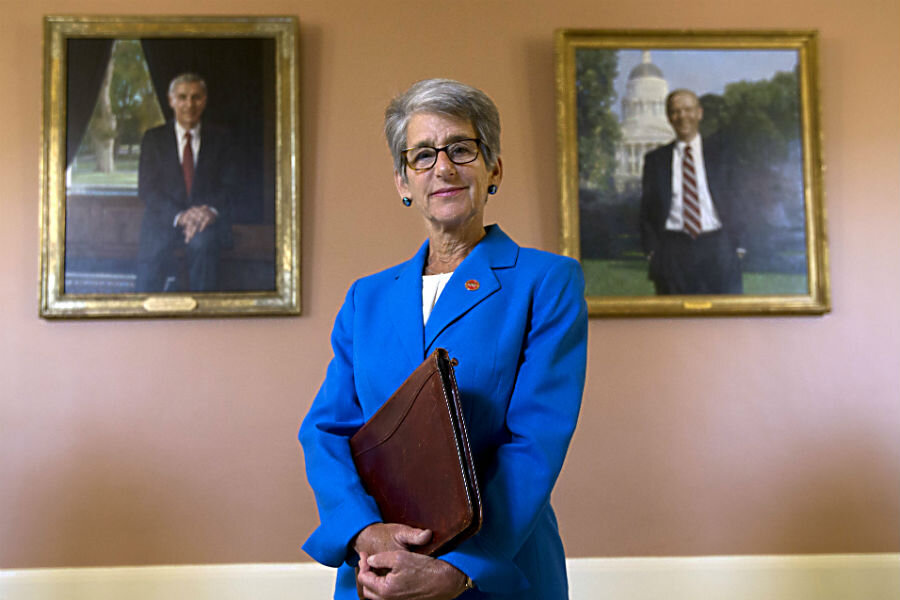

The first woman elected as Oregon's attorney general, Rosenblum is seeking a second term in November.

In California, Hannah-Beth Jackson had long been active in her community beyond her work as a lawyer and former prosecutor, but it took the encouragement of one of her mentors to convince her to run for state Assembly in 1998.

"Women tend to ask permission, and we're never quite sure we are good enough or ready enough," she says. "Men generally don't have those same concerns."

Now in the state Senate, she is chairwoman of the powerful judiciary committee as well as the California Legislative Women's Caucus. Jackson's legislative accomplishments include what was considered the strongest equal pay legislation in the country.

Despite her influence and tenure, the Democratic lawmaker does not always succeed. Earlier this year, a bill she sponsored extending California's family leave protections to small-business employees died in an all-male committee amid concerns of regulatory burdens.

She is undeterred.

"Let's see what happens when I bring the bill back," Jackson says. "Hopefully, that committee will have some women members."