As Congress returns, is it stymied by 'Trump effect'?

Loading...

| Washington

After a relatively productive year in 2015, Congress is again moving at a crawl – even while members say emergencies such as the Zika virus, an opioid epidemic, and the Puerto Rican debt crisis demand urgent attention.

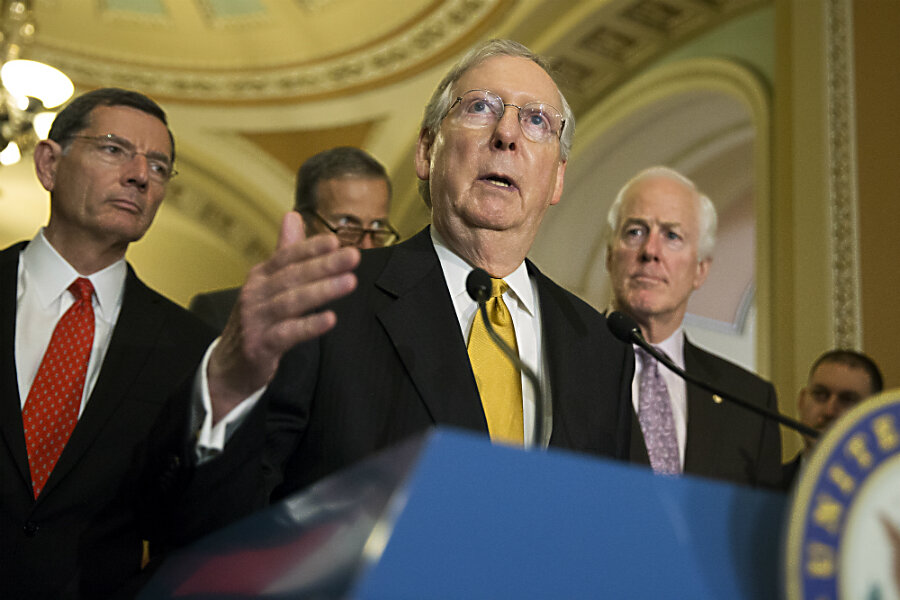

Congress returns this week from its Memorial Day recess with little time left to address those issues and others. Just before their holiday break, Republican Senate majority leader Mitch McConnell complained that Democrats are “making it as difficult as possible for the new Senate” to move ahead.

The same day Senator McConnell spoke, Democratic minority leader Harry Reid was voicing a complaint of his own: that the Senate is scheduled to work the fewest days in 60 years. The annual Senate calendar shows blacked-out days marching across the months – including eight consecutive weeks of summer recess.

What happened to last year’s boomlet of cooperation, when both houses finally passed a highway bill, reformed the No Child Left Behind law, and fixed a longstanding Medicare problem, among other bipartisan accomplishments?

Presidential election years are notorious for skimpy to-do lists. Everyone holds back in hopes that their side will gain the White House. Exhibit A this year is the GOP's decision not to move on President Obama's nomination of Judge Merrick Garland for the Supreme Court.

But this year's accomplishments are more sparse than most, observes political scientist Ross Baker, who just finished a scholar-in-residence stint with the Senate Democratic leadership. He’s predicting an active lame-duck session after the election to deal with the legislative leftovers.

The calendar is one reason for the slowness – the political conventions, for instance, will take up two weeks in July instead of in August. But several other factors come into play, including the staying power of hard-line conservatives, contrasting attitudes about “emergency” spending, and the historic nature of this election year.

“Donald Trump is a singular figure. There’s no nominee quite like him. Without question, he’s a factor in Congress,” says Professor Baker, of Rutgers University in New Jersey. He says Mr. Trump has thrown the GOP into confusion and disorder. “They have spent an enormous amount of time and energy responding to him.”

Consider the week of May 9, when Trump visited Republican leaders on Capitol Hill. The insurgent billionaire, riding high on controversial ideas often at odds with theirs, met many of them for the first time. Prominent among them was a skeptical Speaker Paul Ryan (R) of Wisconsin, who did not endorse Trump until June 2.

The visit dominated the news cycle for days. It consumed the speaker’s regularly scheduled press conference and the line of media questions to GOP lawmakers. In an attempt to turn back the Trump tsunami, the speaker’s office emailed a counter-messaging press release with the subject “What this week is about.”

Indeed, the House managed to pass 18 bills related to opioid drug abuse that week – two months after the Senate overwhelmingly passed its measure. But none of the bills includes emergency funding for the epidemic, which has been underscored by a medical examiner’s finding that the musician Prince’s accidental death in April was caused by fentanyl, a powerful opioid painkiller. Democrats will keep up the pressure for new funding as both houses work to reconcile the bills.

The two parties are also clashing over funding to combat the Zika mosquito virus. Bills passed in the Senate and House differ over dollar amounts, and conferees will have to decide whether to offset a final price tag with cuts elsewhere. In February, well before mosquito season, President Obama requested $1.9 billion in emergency funds to combat the virus. None of the legislation comes close to that amount.

It gets down to a different view over emergency funding, explains Norman Ornstein, a longtime congressional and political observer at the American Enterprise Institute, a conservative think tank in Washington.

“The Zika virus, like so many other things, gets caught because so many Republicans don’t want to do anything without it being paid for. But they also won’t allow any revenues to pay for it,” says Mr. Ornstein. “That’s not only a tragedy but an irony, because the more you wait to deal with this, the worse of a problem it becomes and the worse the cost.”

Even in presidential years, Ornstein says, most Congresses could handle urgent issues such as Zika or the Puerto Rican debt crisis. Puerto Rico has defaulted three times since August, and another deadline looms on July 1. A House committee recently passed a bipartisan plan for Puerto Rico, but some Democrats object and the Senate is waiting to see what the House does. Ornstein calls congressional delay on these issues “irresponsible and feckless.”

This year’s slowdown is also caused by continued dysfunction exacerbated by hard-line conservatives in the House, Ornstein says. They have rejected last year’s bipartisan budget deal, negotiated by outgoing Speaker John Boehner (R) of Ohio, and that has thrown a wrench into the budgeting process. “They can’t get their act together on [spending] bills,” and Congress may be headed toward another budget showdown in the fall, Ornstein says.

That’s not to say that Congress can’t still make headway, or that it’s been a total waste so far this year. For instance, lawmakers have been able to move forward on reforming the Toxic Substances Control Act – a significant piece of legislation on par with some of last year’s accomplishments.

Both sides agree that the Senate, which changed hands after the 2014 election, has been more open and productive under Senator McConnell. On Monday the Senate got back to work on a defense bill, which Republicans have criticized Democrats for obstructing.

“Everybody’s aware that the window is closing,” Senate majority whip John Cornyn (R) of Texas said before the Memorial Day break, according to a report in Roll Call. “But it’s always been that way, and sometimes that creates a sense of urgency and it helps get things done.”