The Bernie Sanders question

Loading...

The script should feel familiar to Hillary Clinton. In 2008, after all, she was Bernie Sanders, pushing the presumptive nominee, Barack Obama, well after the delegate chase seemed lost.

But as Mrs. Clinton moves inexorably toward the Democratic nomination this summer, there is some question about whether this election will continue to follow that 2008 script.

In 2008, Clinton threw her considerable clout behind Mr. Obama, unifying the party for the general election.

Will Senator Sanders do the same? And perhaps more important, will Sanders’s supporters be inclined to listen?

History suggests the answers will be yes. Presidential elections past have often featured bruising primary battles, followed by unifying rallies and upraised hand-holding make-up sessions.

But Sanders’s position both as an insurgent candidate and an independent – and his voters’ deep-seated dislike for political elites – casts some doubt on the traditional calculations.

“A lot depends on what role Sanders decides to play once the contests are over,” says Christina Greer, a political scientist at Fordham University in New York. “When Obama finally won over Clinton, she did a lot of the heavy lifting. She went to at least 37 different major events to try to convince people, her supporters, that Obama was the person they needed to support. Bernie Sanders has already said, that’s not his job.”

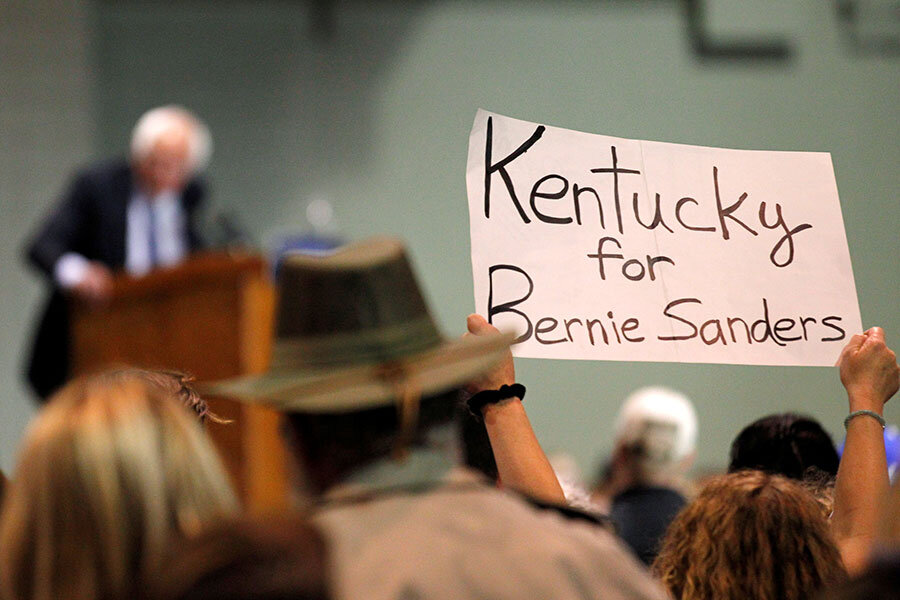

In 2008, Clinton went on to win West Virginia, Kentucky, and South Dakota before the primary season ended in early June. Sanders could do the same. But after Clinton dropped out in 2008, she helped drive 70 percent of her voters to back Obama, despite a bitter campaign, according to polls.

In some respects, this campaign has been less bitter. But what is different is Sanders’s message – and the tone of the entire presidential race this year. Sanders has campaigned to change the system and not simply to represent the liberal wing of a party from which he’s long stood apart, scholars note.

Indeed, as the Vermont senator campaigns for next Tuesday’s West Virginia primary – a working-class state where he leads Clinton in most polls – he sounds similar to the Manhattan billionaire and presumptive Republican nominee Donald Trump.

The day before the Indiana primary, Sanders complained the nominating system was “rigged,” and he lambasted Clinton for essentially using the Democratic Party’s fundraising apparatus as a “money laundering scheme,” funneling donations meant for state party-building back into her campaign.

“I think there are many people around this country – poor people, working people – who believe that the Democratic Party is not effectively standing up [for] them,” Sanders told NPR on Wednesday. “Now, if I lived in McDowell County [in West Virginia] and the unemployment rate was sky-high, and I saw my kid get addicted to opiates and go to jail, there were no jobs, you know what? I would be looking at Washington and saying, ‘What are you guys doing for me?’ And I'm going to look for an alternative.”

The question is whether such rhetoric is so toxic toward the establishment that it turns Sanders’s supporters against Clinton in the general election.

“Will Trump be able to paint her as a conservative, out of touch with her own base and potentially pick up some support in the rust-belt for his more isolationist views, more liberal views on the war, and trade, and engagement for instance?” says Jeanne Zaino, a political scientist at Iona College in New Rochelle, N.Y.

That could be difficult. A new CNN poll finds that Sanders voters prefer Clinton to Trump, 86 to 10 percent.

The greater concern might be that Sanders voters just stay home. That concern is made more acute by the fact that Sanders’s campaign has drawn millions of young and first-time Millennial voters – those who have little affection for political parties and who, demographically speaking, are the least reliable to show up at the polls.

Clinton and her supporters have so far been cautious and respectful, refraining from calling on Sanders to quit the race. Clinton has even declined from claiming the title of presumptive nominee, not wanting to alienate Sanders’s young supporters.

But it might not be enough.

“There’s a great deal of political cynicism right now, and I think Sanders’s message really resonates with that kind of young, liberal point of view with a contempt for politicians,” says Patrick Miller, a political scientist at University of Kansas in Lawrence. “And the kind of voter that he is appealing to is typically much less likely to participate normally.”

This is true of Mr. Trump as well, Professor Miller adds. He is faced with the opposite challenge: Can he get the moderate and establishment voters to turn out?

Supported by a bulwark of black voters as well as a majority of women and older Democrats throughout the country, Clinton has won more votes than any other candidate in the primary season.

But she still has her work cut out for her, says Professor Greer. “She has a lot of negatives, she has a lot of people who do not like her, even among Democrats, and she’s not a charismatic candidate in the same way Obama was in 2008.”