Four ways Iowa caucuses could make Election 2016 clearer

Loading...

| Des Moines, Iowa

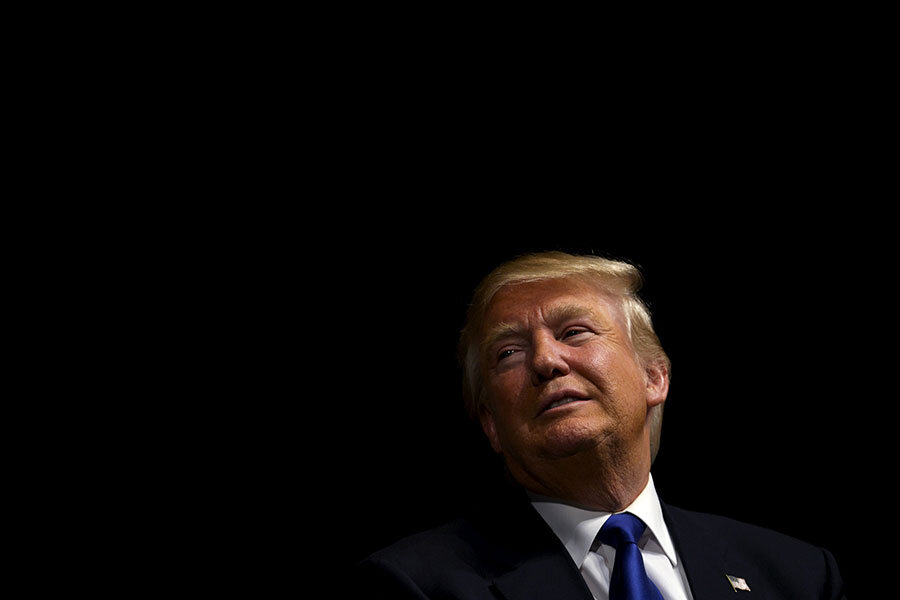

It has been the pre-primary season to end all others: A mega-wealthy reality television star with no prior political experience has taken the Republican Party by storm. On the Democratic side, a self-described democratic socialist is giving the party’s expected standard-bearer all she can handle.

Now, on the eve of Monday’s kickoff Iowa caucuses, voters are about to begin having their say. The latest Iowa Poll, released Saturday evening, shows billionaire Donald Trump regaining the lead over Sen. Ted Cruz, 28 percent to 23 percent, and former Secretary of State Hillary Clinton leading Sen. Bernie Sanders, 45 percent to 42 percent – within the four-point margin of error.

But numbers don’t tell the whole story. In this election cycle, the accepted political wisdom has been chewed up, spit out, and chewed up again. The normal rules just haven't seemed to apply. So what do we actually know about this race? What will we learn as voters (finally) go to the polls?

We are about the get some answers.

The state of polling. Since the advent of modern polling, the industry has never been under more stress. Response rates stand at a paltry 9 percent, with the rise of cellphone use and voters’ growing refusal to take calls from pollsters, according to the Pew Research Center. It’s also difficult to determine who’s likely to vote. Flawed election polls in the United States in 2014 and in Israel and Britain last year have put pollsters on notice in 2016.

“It’s just not clear that traditional polling as we know it has a future,” says Karlyn Bowman, an expert on polling at the American Enterprise Institute in Washington.

One pollster who is universally praised for her work is J. Ann Selzer, who conducts the Iowa Poll for the Des Moines Register and Bloomberg News. Ms. Selzer does her job the old-fashioned way – live interviews with voters on land lines and cell phones, which is expensive.

But the larger world of political polling is in turmoil. For now, the best guesstimate political analysts have comes from averages of recent polls, such as those RealClearPolitics calculates. Averaging dulls the impact of “outliers” and provides a rough sense of what’s happening – unless all the pollsters are making the same mistakes in methodology.

Caucuses are notoriously difficult to poll. Turnouts are very low in Iowa (16 percent in 2012), as caucusing requires a voter to commit to heading out on a cold winter’s evening, arriving at a specific place at a specific time and spending upwards of an hour or two. Determining who will go to that effort can be tough, especially with voters who have never caucused before.

So if, say, Florida Sen. Marco Rubio (currently polling in third place) wins the Iowa GOP caucuses, we’ll know that traditional polling is finished. If Trump and Senator Cruz of Texas are the top two finishers in Iowa, then we’ll know that the Iowa Poll, at least, still has its mojo. Then it’s on to Feb. 9 and the New Hampshire primary, where analysts are less confident of any individual poll.

Also, beware drawing any conclusions much before any state holds its vote. Some voters settle firmly on a candidate quite late – sometimes even the day of the vote.

Mr. Trump’s ground game. One of the abiding mysteries of the 2016 cycle is how well organized Trump is on the ground. Senator Cruz has famously set up “Camp Cruz” in Iowa – volunteers from around the country there to canvass and make calls – and has similar efforts in New Hampshire and South Carolina.

Trump’s get-out-the-vote effort is less clear. If he’s super-organized, his campaigning isn’t advertising it. Some analysts point out that Trump’s Iowa campaign director, Chuck Laudner, worked for Rick Santorum’s winning Iowa effort four years ago – and that Mr. Laudner knows how to build a database.

But if a significant number of Trump supporters are flying below the radar – that is, not showing up in databases – it may be that Trump will have to rely on his supporters to activate themselves.

“Turnout is basically what separates Trump and Cruz right now,” said Patrick Murray, director of the independent Monmouth University Polling Institute in West Long Branch, N.J., in a statement. “Trump’s victory hinges on having a high number of self-motivated, lone wolf caucus-goers show up Monday night.”

How Trump or Cruz handles losing. Perceptions of Iowa’s results will rest in part on expectations. For a while, it was looking as if Cruz would win Iowa, and Trump come in second. The billionaire could have spun a loss as expected and then moved on to New Hampshire, where he seems to have a firm lead (if the polls are to be believed).

But now, Trump is ahead in Iowa polls, albeit not by much. Whichever candidate loses, Trump or Cruz, he will have some explaining to do.

“We have some fairly immature people in there this cycle,” says Cal Jillson, a political scientist at Southern Methodist University in Dallas. Trump would claim “he’s been robbed,” and Cruz would claim “the establishment has risen up to bat him down,” Professor Jillson says.

The stakes are higher for Cruz, who almost certainly needs to win Iowa to springboard into the next contests, where he currently trails. But if Cruz pulls off a win in Iowa, and Trump loses, what will The Donald say? After all, Trump is all about winning.

Trump biographer Gwenda Blair sees a way forward for him: declare victory anyway, and move on. In an interview, she recalls watching Trump in the early 1990s in West Palm Beach, Fla., where he had two buildings of condo units that didn’t sell and went into foreclosure.

“There was a public auction, which you might have thought was embarrassing. Not to him,” Ms. Blair says. “He was there, walking around, ‘Best day of my life, these people buying units are winners… This is a great opportunity, it’s all going great, good time to invest.’ He was a winner.“

How Clinton or Sanders handles losing. As with the Republican candidates, questions abound on the Democrats’ turnout operations. Senator Sanders of Vermont has lots of young enthusiasts and a majority of Democratic men on his side, while former Secretary Clinton wins big with women and minorities (though Iowa’s minority population is small).

Still, all the enthusiasm and impressive poll numbers in the world don’t mean anything if the voters don’t show up. Eight years ago, Clinton came in third in the Iowa caucuses, behind Barack Obama and John Edwards, and her back was against the wall. She had to win New Hampshire to still appear viable, and she did, taking the nomination battle with then-Senator Obama all the way into June of 2008.

This year, Team Clinton is doing all it can to make a better showing. Sanders has a good turnout operation in Iowa, but it’s not as good as Obama’s was in 2008, according to political communication expert Joshua Darr at Louisiana State University in Baton Rouge, writing at FiveThirtyEight.com.

Clinton could still lose both Iowa and New Hampshire. And if so, her campaign sees the South as her firewall, where there’s a greater proportion of minority voters. But she will have to display nerves of steel, and not betray any doubt that she can prevail – despite likely hand-wringing by the Democratic establishment and over-reactive media. Given her performance in 2008, it seems safe to say that Clinton will hang tough.

If Sanders loses in Iowa, he can take heart that he’s still a strong front-runner in New Hampshire. But the reality is that if Sanders loses Iowa, his climb to the nomination will be mighty steep. In the 2008 Democratic caucuses and primaries, Iowa had the third-highest percentage of white liberals (50 percent) after Vermont and New Hampshire, according to exit poll data compiled by FiveThirtyEight.

So Iowa should be his to lose. But if Sanders does lose, here’s a safe prediction: He probably will not emit a hoarse scream from the stage, as in 2004, when another Vermonter fell short of expectations in Iowa and tried to rally his troops with a display of exuberance. The “Dean scream,” by former Gov. Howard Dean, remains high on candidates’ list of “what not to do” after losing a race.