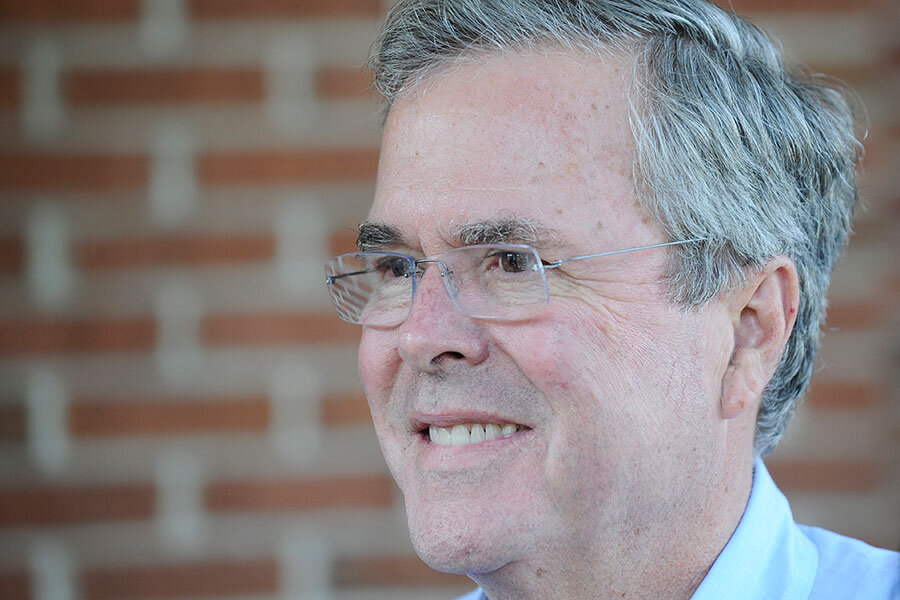

Can Jeb Bush rise again? Florida could hold clues.

Loading...

| Fort Lauderdale, Fla.

It was the tennis match of the century, Washington-style: Jeb Bush and brother Marvin versus two women champions, Chris Evert and Pam Shriver.

Then-President George H.W. Bush set up the 1989 match, which took place on a private court in the Hart Senate Office Building. VIPs were bused in to watch. All White House business ground to a halt. The Bush boys won in three sets.

“We foolishly took the challenge lightly,” Ms. Evert told The Washington Post.

The point, too, is that Jeb and Marvin had practiced – hard. Because they’re Bushes, and they play to win.

Twenty-six years later, presidential candidate Jeb Bush is in a deep hole in the highest-stakes match of his political life. Even in Florida, where he served two terms as a popular governor, the latest poll of Republican voters has Mr. Bush in fifth place at 9 percent. Donald Trump leads with 36 percent. At the Florida GOP’s recent Sunshine Summit in Orlando, some Bush supporters wondered quietly if his presidential quest is effectively over.

But longtime observers of Bush don’t see him giving up anytime soon. His recent hiring of a speech coach, with apparently positive results, goes to the Bush family never-say-die spirit.

Behind that determination, though, lies a deeper question: How did the once-golden child of the Bush political dynasty – the one who was supposed to reach the presidency before his less studious older brother, George W. Bush – fall so far behind? Was he a better campaigner when he ran for governor? Did the game change or did he?

The answers are multilayered, say longtime Florida political observers. Bush’s style hasn’t really changed, though he's gotten grayer. But the game has changed.

The last time Bush ran for office, for reelection as governor in 2002, social media didn’t exist. And the mojo he once had as a leader of the conservative small-government rebellion has passed. Now he's best known for two issues that make most conservatives bristle – comprehensive immigration reform and Common Core education standards.

Then there’s the the unpredictable X-factor, whose impact cannot be underestimated: the outsize personality of Mr. Trump, who spent the summer slamming Bush as “low energy.”

Place these challenges against the high expectations Bush faced, and his fall seems precipitous. Leading Republican figures, especially in Florida, flocked to his camp. In the first six months of 2015, the family Rolodex helped Bush raise a stunning $103 million for his super-political action committee.

But history has shown that big money guarantees nothing, and the Bush who some say should have been president now finds himself in need of some of the skills that characterized the brother who was.

“I was never a strong believer he’d be an overwhelming favorite,” says Matthew Corrigan, a political scientist at the University of North Florida in Jacksonville and author of a 2014 book on Bush’s governorship, “Conservative Hurricane.” “He’s not a glad-handing politician; he’s not his brother.”

But Professor Corrigan has been surprised by how the always-prepared Bush has made what seem to be elementary mistakes. There has been a lack of message consistency, such as his stumbling responses on his brother’s 2003 decision to invade Iraq. Another surprise is that Bush’s campaign didn’t respond more forcefully to Trump’s “low energy” charge.

'He was like Marco Rubio'

When Bush first ran for Florida governor in 1994, his political persona was different. He was seen as the young hotshot going after a political legend, old-time Southern Democratic Gov. Lawton Chiles. Bush ran as a strong conservative, perhaps a little too strong, Corrigan suggests in his book, and almost beat him.

“He was like Marco Rubio, the new, younger guy, going after Chiles, who had been around forever,” says Brad Coker, managing partner of Mason-Dixon Polling & Research in Jacksonville, Fla. “He was the young up-and-comer.”

When Bush ran for governor again four years later, he won easily. But even then, nobody ever accused him of relying on charisma to win over voters, unlike his folksier older brother, who did defeat a Democratic political legend – Texas Gov. Ann Richards – in his first try.

“There’s no getting away from it, Jeb’s a policy wonk,” says Sherry Plymale, a longtime Bush ally who worked in state education policy. “Nothing pleases Jeb more than to sit around in a group and get to the bottom of an idea. He’s always been like that – more so than his brother, who was a delegator.”

But many of the Florida political observers interviewed reject the idea that Bush was ever “low energy.” They recall his ambitious conservative agenda, his effective response to multiple major hurricanes, and his nickname, “Veto Corleone,” for the 2,549 line-item vetoes that cut millions of dollars in government spending. But today the “low energy” slam continues to dog him. Conservative talk-radio host Rush Limbaugh invoked it on NBC’s “Meet the Press” Sunday, and raised a related question: Does Bush really want to be president? Just the asking of the question is devastating.

Bush didn’t help matters last month when he suggested, with exasperation, that he wasn’t eager to take on the gridlock and partisanship in Washington. “If this election is about how we’re going to fight to get nothing done, then I don’t want any part of it,” he said at a forum in South Carolina.

When asked directly a week later if he still wants to be president, the Floridian answered the only way he could: of course.

“We have to fix some really big, complex things, and I have the leadership skills to do it, and I'm fired up about that,” Bush told Chuck Todd on “Meet the Press” on Nov. 1.

But there’s a big difference between saying you’re fired up, and being fired up, à la Trump.

Bush is the way he is – a doer and not a talker, as he himself says. “Jeb Bush is a gentleman who was raised to be polite,” says Ms. Plymale. “But you cannot be a successful governor of a state like Florida and be as active as he was, and be low energy.”

High energy governor

After Bush lost the governor’s race in 1994, he essentially kept running. He dialed back some of the hard-line language, and won the post easily in 1998. But there was no mistaking that Bush was a conservative – or that he was a strong executive.

Corrigan calls Bush “the most powerful governor in Florida history.” Bush benefited from changes to the state constitution that gave the governor more power, and from the emergence of the Republican Party as a force in Florida. But the force of his own vision was also key in enacting a strong conservative agenda, including: tax cuts, education reform (including private school vouchers for children in low-performing public schools), and an end to affirmative action in state universities.

Bush also won kudos from social conservatives nationally for intervening in the case of Terri Schiavo, the brain-damaged woman whose husband sought to end life support.

But to some Republicans today, none of that matters. Sid Dinerstein, former chairman of Florida’s Palm Beach County Republican Party and a one-time Bush supporter, sums up his objections with two terms: Common Core and “amnesty,” his shorthand for Bush’s less-than-conservative positions on education and immigration.

The “body-snatchers” got hold of him, says Mr. Dinerstein.

And what about Bush’s campaign skills?

“When he ran for governor, those of us on his side found him very inspirational,” Dinerstein says. “He had a strong moral compass, and he was not overly full of himself. At some of the state committee meetings, we’d get into smaller discussions, and he was an honest guy. You could talk to him.”

But to Dinerstein, substance matters far more than style. Bush left office in January 2007, and remained active on the two policy matters – education and immigration – where conservatives today are most critical of him. And to most voters, even in Florida, Bush has been out of sight. That meant, for the most part, building his brand from scratch.

For Bush, his last name adds to the list of challenges. Not only is “Bush fatigue” rampant among voters, but his political lineage has also added to the impression that he may be running out of a sense of familial duty.

Lighting up the room

Bush defenders say that he’s working as hard as anyone in the GOP field and reject the idea that he should drop out to allow the younger, fresher, more charismatic Rubio to consolidate establishment support and stop the Trump-Ben Carson outsider bandwagon.

“I don’t think that Jeb’s done yet. I don’t think it’s his swan song at all,” says Plymale. “He’s smart and knows how to run a campaign. This time has been a little odd, but I do think we’ll see things evolve.”

Mr. Coker, the Florida-based pollster, isn’t so sure.

“When he was governor, there was a mojo there,” says Coker. “He was leading the parade in terms of public policy: We’re going to change this, we’re going to cut government, we’re going to cut taxes. Now he’s just not the same. I think people in Florida have noticed it, too. They like him, but he’s not exactly lighting up the room.”

The mechanics of modern campaigning could be a factor. Back in 2002, campaigning was a linear process: Go to an event, give a speech, shake hands, get in the bus, head to the next stop. There was no Twitter, no Facebook, no Instagram, no instant communication available to go right at a voter.

“There was no way to turn TV news on its head in 30 minutes by tweeting out something, the way Trump does,” says Coker. Today, candidates and their campaigns have to multitask like never before.

At the recent Sunshine Summit, where the Republican candidates spoke, Bush’s energy level didn’t appear like it did when he ran for governor, says political scientist Susan MacManus, a longtime observer of Florida politics at the University of South Florida in Tampa. She also observed a lot of energy for Rubio, especially among the younger attendees. At a stand selling candidate pins for a dollar, Rubio was way ahead.

“I wouldn’t go by that,” she says, “but it told me something.”

On this date eight years ago, in the last open-seat presidential race, former New York Mayor Rudolph Giuliani dominated the GOP field with an average 28 percent and the eventual nominee, Sen. John McCain of Arizona, languished in fourth place at 12 percent.

Senator McCain ended up winning the New Hampshire primary, and the rest is history. Bush’s dream of making history may be fading, but especially in this unpredictable presidential cycle, it’s not gone.