How to fix Congress: A former House speaker calls for fewer ethical 'mousetraps'

Loading...

| Washington

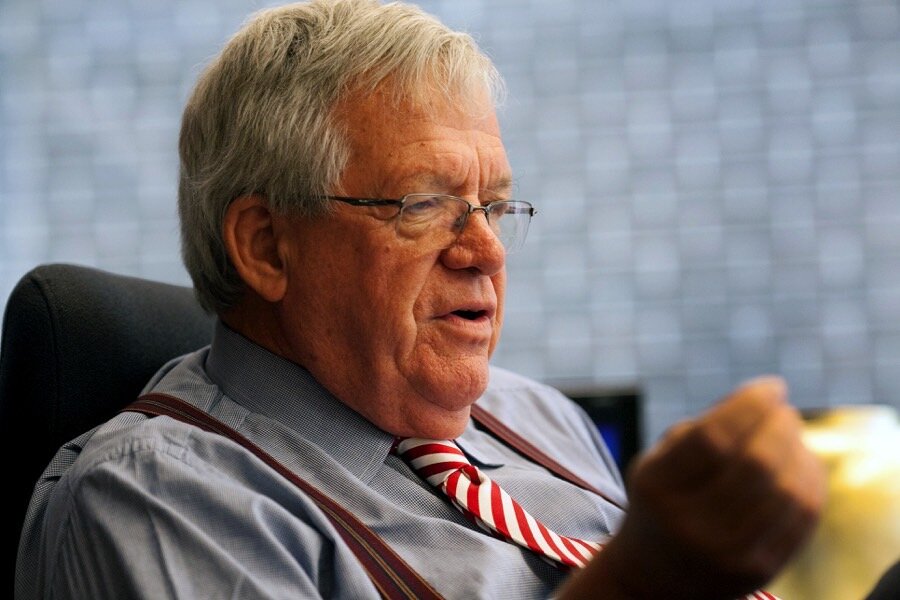

Dennis Hastert, the longest-serving Republican speaker of the House, describes life in Congress as “being locked up in some isolated dodge-ball game.”

He lived through a historic era of openness and transparency on Capitol Hill, including new rules on ethics and campaign finance, the introduction of cable television on the floor of the House and Senate and 24/7 media coverage, and unprecedented, real-time access to documents and committee proceedings on the Internet. But he left a Congress deeply divided along partisan lines and largely gridlocked.

Now, he says, Congress needs to dial back some of the institutional reforms it has enacted in the past couple of decades and not overreact to the nonstop din of the media.

Mr. Hastert stepped down from leadership after Republicans lost their majority in 2006 midterm elections, and retired from Congress in 2007. Now a lobbyist, he spoke to the Monitor in his Washington, D.C., office, sitting comfortably in red suspenders behind a large, spare desk.

How Congress has changed since he first arrived in Washington.

Congress was a collegial group of people who may have debated with great passion, but at 4 or 5 o’clock they would sit down and have some kind of libation with each other and shoot the breeze. It was a different work ethic, a different consciousness.

In the old Congress, not every vote was a tallied vote. Bills could pass by voice vote or consent or teller vote. It was easier to pass legislation because you could vote your conscience on a bill and not worry about getting it reported in the tea party news. When TV became prevalent, all of a sudden everything was a show. Everyone had to pontificate. The process became much more ponderous.

The importance of holding hands.

People called me “speaker” but I always thought “listener” was the better title. I spent most of my time in the backroom, day in and day out, with members of Congress on both sides of the aisle trying to work out problems that people had [in trying] to move legislation. It took me three times to pass [the Medicare prescription drug benefit] and get it through the Senate. I spent a lot of time holding people’s hands and engaging. I don’t think leadership [today] takes the time to try to engage people and work out problems.

The ‘smoke-filled backroom’ gets a bad rap.

There are three different kinds of days in Congress, figuratively speaking. You get there on a Tuesday and have some issues you want to move. Tuesday is the day of “no.” It’s the day you assess what your numbers are. Wednesdays are meat-grinder days. You sit at a desk and try to work out all the problems. You need 218 votes. Somebody has to give up something to get things done. Thursday is the day you got things done. It takes time. It takes bringing people together.

Let’s meet in private.

I rarely went to the House floor. If you want to see me, come to my office and we’ll work things out. But in public, with everybody looking at you, listening to what you’re saying, you really can’t get things done on the House floor.

How to deal with insurgent freshmen, including tea partyers.

[You] have to find something new members are interested in. If you give them a project that involves moving legislation, they find that once they are involved in a process, there has to be give and take. It can’t just be all one way or another. You have to make them part of the process, not part of the problem.

It’s time to loosen the ethical straitjacket.

There needs to be less “gotcha.” You’ve got a thousand people out there watching everything you do.... Someone is always trying to trap you into doing something, to tag you with a paint gun. Let Congress do its work! You wouldn’t take a person who’s the head of a Fortune 500 company and say “you can’t meet with these people that make your product” or “you can’t meet with the people who transport your product.”

[With new ethics rules] a member of Congress can barely sit down with someone to have a cup of coffee. Congress needs to be engaged. They need to talk to people on all sides of all issues, and it’s not always done in your office. [Now] you have to be isolated in this little world with no communication. That’s crazy. You have to make good decisions off of good information.... You wouldn’t put these constraints on anyone else, but you’re putting them on the people who run your country.

Where we do need transparency.

Change the campaign system. Let members raise money. Let it be transparent. Let the chips fall. The best reform you could do as a Congress is [to replace campaign finance rules with] transparency. If you want to change the campaign system, it’s easy to do: Raise at least half the money in your campaign in your district; put it up on the Internet within 20 hours. It’s complete transparency so the press and voters know where the money is coming from. If they raise money in their own district, they’re not running off to Wall Street or Hollywood. Let them raise their money where the voters are.

Get rid of the stigma and restrictions surrounding trips.

All Congress does is put mousetraps around, and [lawmakers are] going to get their toes snapped. Members of Congress need to be engaged because they are on a world stage. They need to go to the Middle East. They need to have a dialogue with people in the Ukraine to know what this is about. When [voters and the media] bash people who take trips, or “codels,” you’re defeating having somebody who is educated and knowledgeable and can make good decisions about problems.

The value of more doing and less preening.

Value the workhorses. Show horses are pretty and they whinny nice. But the people who really do the work aren’t necessarily the people out there putting their feathers out like a peacock all the time. The workhorses are the ones you see working hard in those subcommittee meetings that television doesn’t cover. They’re putting ideas together, putting people together, and they’re working hard. That’s not necessarily a showy business.

- Monday, a political science professor and analyst from a Washington think tank gives her perspective on how Congress can be fixed.