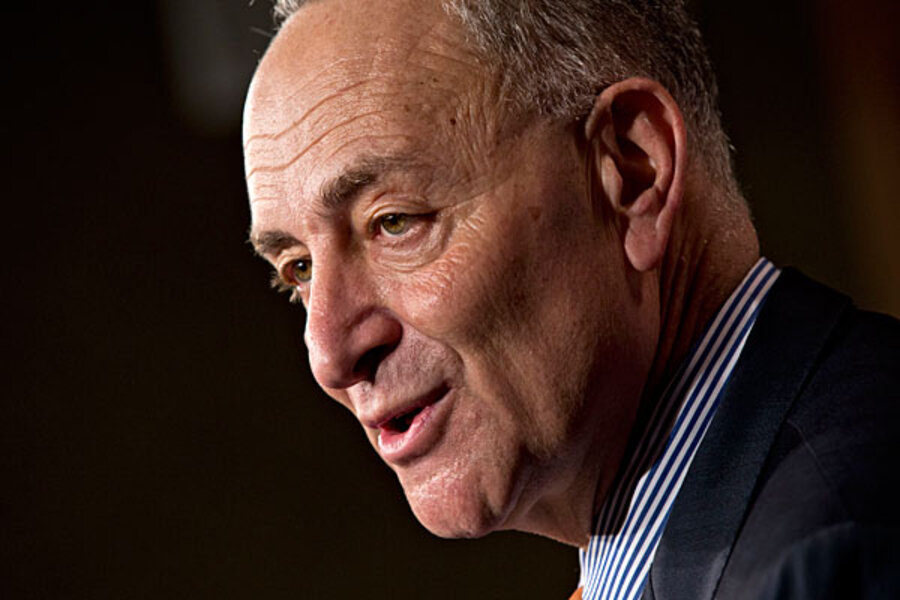

How Chuck Schumer plays the congressional chessboard

Loading...

| washington

In the run-up to the November elections, Chuck Schumer worked tirelessly in attacking Republicans, from congressional conservatives to GOP frontman Mitt Romney. Since then, New York's senior Democratic senator has clocked more hours negotiating with his Republican colleagues than anyone else on his side of the aisle.

Part of this reflects the natural rhythm of politics: The year after a presidential election can often be Washington's most productive. But a man who has spent his life in Congress shifting between expert political hatchet man and tenacious dealmaker may also sense a moment when the Republicans are particularly vulnerable – or receptive – to cutting deals as a result of changed dynamics on the Hill.

"He's a great legislative chess player and knows intuitively when it's time to strike and when it's time to wait," says Jim Kessler, a longtime Schumer staffer and now a senior member of the Third Way, a Democratic centrist think tank.

Clearly, the voluble senior senator thinks it's time to strike. First, he teamed up with a crew of other Senate veterans, led by John McCain (R) of Arizona and Carl Levin (D) of Michigan, to hatch a compromise forestalling sweeping changes to the Senate's filibuster rules.

Then there's Senator Schumer's long-unrequited love, immigration reform, in which he leads the Democratic contingent in the bipartisan "Gang of Eight." That's the group in the Senate that many lawmakers and advocates believe will deliver the opening bill in the immigration-reform debate in early April.

Finally, there's the continuation of Schumer's legacy in the House, where his determination to pass the 1994 crime bill (containing a ban on assault weapons, among other provisions) is carrying over to President Obama's push to strengthen the nation's gun laws. Schumer went right for the "sweet spot," as he calls it, of universal background checks in negotiations with staunch pro-gun lawmakers like Sens. Joe Manchin (D) of West Virginia and Tom Coburn (R) of Oklahoma.

While prospects for a background check deal have dimmed, it is the proposal that perhaps best explains Schumer: Background checks are widely regarded as the most impactful piece of legislation gun-control advocates in Congress could dream of passing – if someone would take on the task of finessing the details behind the scenes to bring Republicans and centrist Democrats on board.

As the third-ranking Democrat in the Senate, Schumer is one of the left's premier political strategists and spokesmen. Though he clearly relishes political combat in the right venue – he's a two-time leader of the typically thankless chairmanship of the Democratic Senatorial Campaign Committee – he represents a particular breed of dealmaker: someone who combines policy understanding with a keen political sense and an intuitive knack for legislating. He also knows where the money is.

"Schumer has power to do this because of the stature he's earned in the party in terms of money and distribution of campaign funds," says Julian Zelizer, a congressional historian at Princeton University. "And his role in the leadership gives him a little clout and a little more flexibility to make these kinds of deals."

To be sure, Schumer is often lampooned as hurtling from one television camera to the next, someone never far from the klieg lights. But Schumer also understands how to keep politics and policy in proper perspective.

"He has very few permanent enemies," says Mr. Kessler. "If people play fair, even if they play rough and hard, he thinks, 'That's the way this is done and that's OK....' For someone with as many rough edges as a Brooklyn Democrat often has, he seeks out the genuineness of other people intuitively and will find a way to work with them."

(He's also known to harbor another intuitive talent – finding romantic connections between his staffers. One recent New York Times profile called him the "Yenta of the Senate.")

Unlike some lawmakers on the Hill, Schumer revels in the boisterous process of legislating. It's in his DNA. In 1998, he turned down a potential run for governor of New York to enter a messy Democratic Senate primary for the right to challenge then-Sen. Al D'Amato (R).

"In Congress, I really found my métier," Schumer said during a campaign stop that year. "'I love to legislate. Taking an idea, often not original with me, shaping it, molding it. Building a coalition of people who might not completely agree with it. Passing it and making the country a little bit of a better place. I love doing that. The Senate desperately needs legislators. The old-time legislators are gone."