Has Mitt Romney given up on the Latino vote?

Loading...

| Washington

Mitt Romney, a white guy, has put another white guy, Rep. Paul Ryan, on the Republican ticket as his running mate. And on Tuesday, yet another white man – Gov. Chris Christie of New Jersey – was given the coveted role of keynote speaker at the Republican National Convention later this month.

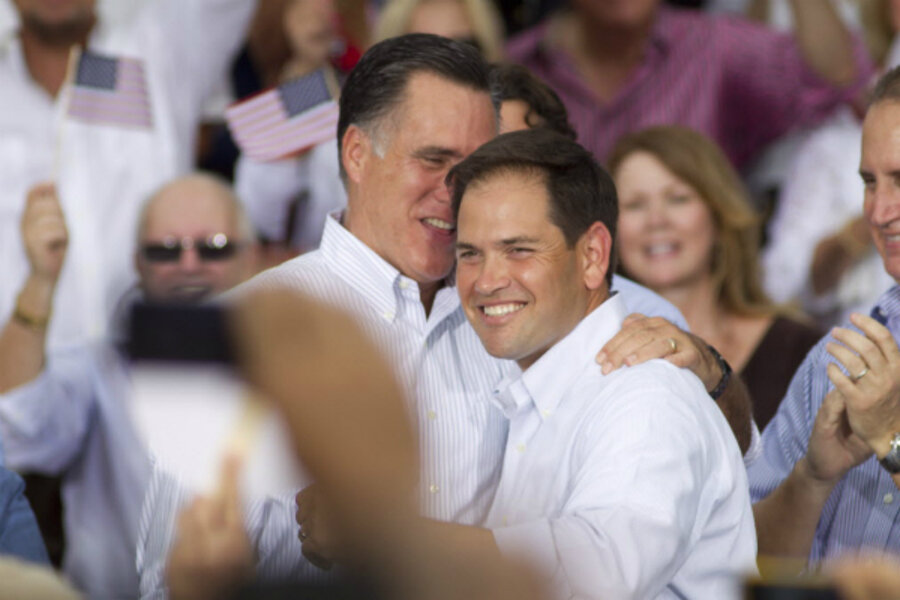

To be sure, there will be plenty of ethnic and gender diversity on display at the Tampa, Fla., conclave. Home-state Sen. Marco Rubio of Florida will introduce Mr. Romney before his big acceptance speech on the final night. Gov. Susana Martinez of New Mexico will speak, as will Gov. Nikki Haley of South Carolina, who is Indian-American.

But having forgone a minority or a woman for the ticket, Romney has made another telling choice with a keynote speaker who is also neither – particularly in not selecting a Hispanic. Two people who could easily have filled the keynote slot were Senator Rubio and Senate candidate Ted Cruz of Texas, another rising Latino star in the GOP.

After African-Americans, Hispanics are the largest minority voting bloc and crucial to both campaigns. Team Obama has given Hispanics prime roles at the Democratic National Convention in early September: Mayor Antonio Villaraigosa of Los Angeles is chairman and Mayor Julian Castro of San Antonio is keynote speaker.

So has Romney given up on the Hispanic vote? Not necessarily, analysts say.

“I wouldn’t say that he’s written it off,” says Sylvia Manzano, senior analyst at Latino Decisions polling firm.

Ms. Manzano notes that Romney’s first event Monday morning – the first business day since Ryan joined the ticket – was in a Cuban-American neighborhood in Miami, at a Latino-owned business. “That was a deliberate choice,” she says. “And the party has some high-profile Latinos speaking at the convention.”

But the fact remains that, in elevating Ryan and Christie, Romney has chosen to fill other needs besides outreach to Latino voters.

“The Ryan selection represented a realization on the part of Romney and his advisers that he couldn’t win the election by being Not Obama,” says Dan Schnur, a former Republican strategist who advised John McCain’s 2000 campaign.

Mr. Schnur calls the Ryan choice risky, because it puts so much focus on Ryan’s signature issue, entitlement reform – often called the “third rail” of American politics. “The risk is whether this is the Not Obama you want to be,” says Schnur, director of the Jesse M. Unruh Institute of Politics at the University of Southern California in Los Angeles.

The choice of convention keynote speaker is far less important than running mate, but it still has significance that is more than symbolic.

“You want someone who is inspirational, and you often want an attack dog,” says Kenneth Sherrill, a political scientist at Hunter College in New York City. “This is where Christie really is strong.”

Of course, the charismatic Rubio, too, could have delivered the red meat that gets convention-goers revved up. But it’s possible that Romney calculated he had a better shot at winning over white, ethnic Catholics than Latino voters, and thus the choice of Christie, who is Italian and Catholic, Mr. Sherrill says. (Ryan is Irish-Catholic, though those attributes weren’t the main reason to put him on the ticket, analysts say.)

Romney has struggled throughout the campaign to attract significant Hispanic support. The latest Latino Decisions poll of Hispanic voters, taken in July, shows Obama beating Romney 70 percent to 22 percent. That’s well below President George W. Bush’s performance among Latinos – at or above 40 percent in both of his presidential runs – and below John McCain’s 31 percent (to Obama’s 67 percent) four years ago.

As the second President Bush showed, Romney doesn’t need to win the Hispanic vote, he just needs to do well enough.

“It’s very difficult to see him winning without support in the mid-30s range of Hispanic-American voters,” says Schnur.

But, he says, the missed opportunity with Latino voters might not have been with the vice presidential selection, but in passing on Rubio’s version of the DREAM Act. Rubio had been working on legislation similar to a bill Democrats have long championed that would grant legal status to young undocumented immigrants who had been brought into the country as children. When Obama announced a policy directive in June to halt deportations of such young illegals, Rubio suspended his legislative efforts. That policy goes into effect on Wednesday.

The Romney-Rubio moment on a Republican version of the DREAM Act could have come before Obama’s move.

“When Rubio came out with his DREAM Act, he was throwing Romney a life line,” says Schnur. “It might have been a less aggressive version, but it would have framed the debate as one DREAM Act versus another.”

Early in the 2012 campaign, Romney adopted a hard-line approach to immigration, and suggested in one of the GOP primary debates that a solution could be “self-deportation.” Many Latinos did not take kindly to that term, and have had a hard time hearing other aspects of Romney’s message.

Republicans like Cruz and Rubio have long argued that Hispanics have a natural home in the GOP, given their emphasis on entrepreneurship, family, and faith. The Romney campaign has hoped that its economic message would attract Latino voters, who point to the economy as their most important issue.

“But immigration is a threshold issue” for Latinos, says Schnur. “You’re not going to listen to what someone has to say about jobs and taxes if you don’t think they respect you and your family and community.”