A poll-taker's technique to get you to respond: 'Smile while you dial'

Loading...

| Omaha, Neb.

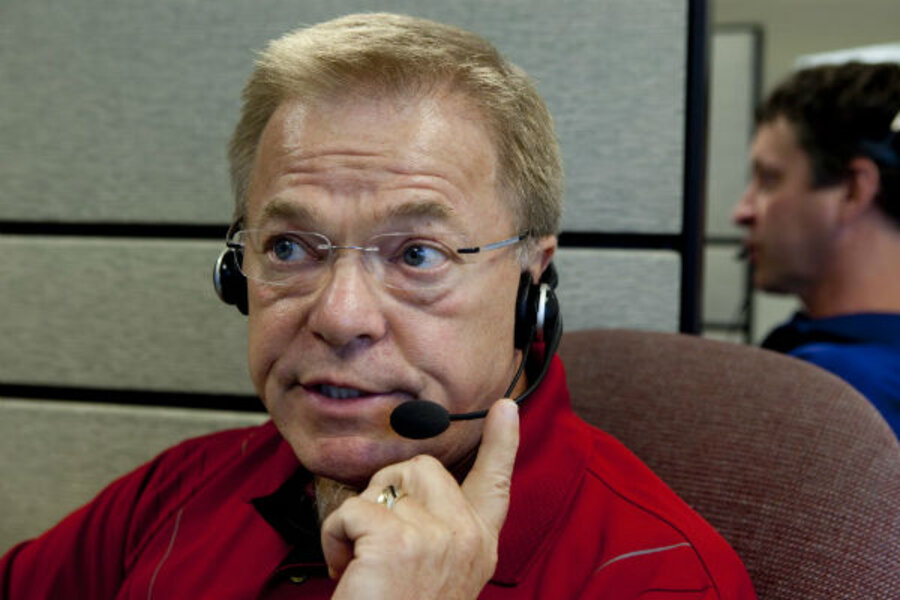

Ed Dubas is one fast talker. He has put this skill to good use over the course of his working life – as a mayor of the small Nebraska town of Fullerton and a used-car dealer.

Now, this bespectacled grandfather of three with the smooth voice and easy way with words could be phoning you. He is a Gallup Poll interviewer; and each of the past five years, Mr. Dubas has been the best at it in the company's global business of conducting political and corporate polls. He is on track to complete his 100,000th interview for the company by year end.

His secret?

"You smile while you dial," Dubas says from his cubicle at Gallup's Omaha call center in an office park outside the downtown area.

Dubas is one of approximately 900 interviewers tasked with executing Gallup's polls. He says Gallup's callers get paid by the completed survey, so Dubas doesn't mess around. Having grown up one of eight children on a farm, he was weaned on long days and hard work. At Gallup, he says he takes as much overtime as possible, and 15-hour stints aren't outside his norm.

During a time in life when many people look toward retirement, Gallup has given Dubas – now 60 – a next professional act. He says he loves what he does. Like many of his colleagues, Dubas views Gallup's mission to document the will of the people as a public service. But Americans, inundated with calls from pollsters of all persuasions – and intentions – and folks peddling stuff, can be wary of a stranger seeking personal views. Hang-ups are not uncommon. Respondents aren't always shy with four-letter words.

"It's kind of like a sales business," Dubas says. "If you've ever been in the used-car business, rejection is something you get all the time. If you get turned down on the phone you don't have to feel bad about it because you don't even see who you're talking to."

Dubas says he aims to be polite and neutral; the latter is a key value Gallup instills in callers during training, instructing them never to interpret questions for respondents.

"Getting someone tough on the phone doesn't bother him," supervisor Jenny Higgins says of Dubas.

During a recent call session, Dubas wore a headset and leaned back in his chair, spinning a red pen in his hand with a determined intensity. He asked permission before launching into an interview. His work, like that of all Gallup callers, is recorded and randomly reviewed by the quality control staff at Gallup's sprawling riverside complex up the road.

Dubas enters answers into a computer. He keeps callers on the phone with positive feedback. "I'm just about finished," he says. "And I sure appreciate your time." And at the end, much as he might have waved as a satisfied customer drove off his lot, he offers gratitude for the transaction. "Thanks for your time and for being so polite, ma'am," he says to one respondent.

"My ultimate goal is to help everyone be heard and make them feel good in the process," Dubas tells the Monitor. "The good [responses] far outweigh the bad."

One of his wackiest interviews came when a man, reached on a cellphone, declined to talk. "We got to the hospital. We're delivering a baby," he told Dubas, obviously aiming to end the call. But the man's wife had other plans. Dubas says he heard her say, "Give me the phone, the contractions aren't close." She completed the survey.

"Other people say, 'I've been waiting all my life to do a Gallup interview,' " Dubas observes.