The faith factor: Religion's new prominence in campaign 2012

Loading...

| Philadelphia

God hit the campaign trail way back in the summer of this election cycle. Rick Perry asked His blessings on President Obama while Michele Bachmann wondered if earthquakes were His wake-up call and Jon Huntsman Jr. tweeted that evolution is "part of His plan." Ron Paul invoked Old Testament warnings against anointing a king. Newt Gingrich hit hard on repentance and forgiveness. And apparent front-runner Mitt Romney said it would take an "act of God" for feisty Rick Santorum to win the nomination. Mr. Santorum, for his part, accused Mr. Romney of believing he's ordained by God to win.

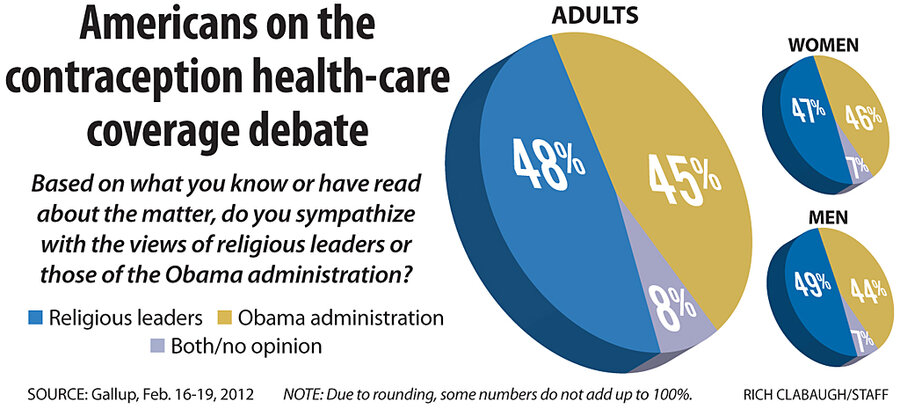

Republicans may have brought religion to the stump early this election season, but it was the Democrat in chief who really put God into play. In February, at a national prayer breakfast, Mr. Obama actually gave a scriptural rationale – "for unto whom much is given, much shall be required" (Luke) – for tax increases. But then he caused a firestorm among religious believers and sympathizers when he unleashed federal muscle against the very voters his Bible-quoting may have been designed to attract. Under Obama's Affordable Health Care Act, health insurance plans now must cover contraceptives, sterilization procedures, and what many consider abortion-inducing drugs, even for employees of Roman Catholic universities, hospitals, and charities, and other religious groups morally opposed to providing such services. A tiny, government-defined group of religious employers – mostly churches – is exempt from the mandate. As for the rest, the administration withheld from them the sort of conscience accommodations government historically offers in religious liberties situations.

In the process, the president himself created a campaign issue for the 2012 election and crystallized the intensifying and hardening political battle in America over whose beliefs matter.

As never before, religion is an issue in the 2012 election, say experts.

"Religious currents are more pervasive and more multifaceted than ever in shaping the public debate," says Allen Hertzke, a professor of political science at the University of Oklahoma in Norman. While religion historically has influenced politics, affiliation was typically the dividing line: Protestants voted Republican and Catholics voted Democratic. "Patterns now suggest something unusual in American politics – division along the lines of salience of religion" itself, says Professor Hertzke. "This year, it has intensified."

The enduring points of division seem to be legal abortion and gay marriage – issues unimaginable a generation ago, when compromise characterized politics. "If someone is a Republican or Democrat because of the abortion issue, they tend to interpret a whole range of issues through that lens," says John Green, a professor at the University of Akron in Ohio.

This year, the arena of reproductive issues and health care in general has spilled out into a battle over religious liberties. And though it roughly follows party lines, for some the issue crosses partisan boundaries.

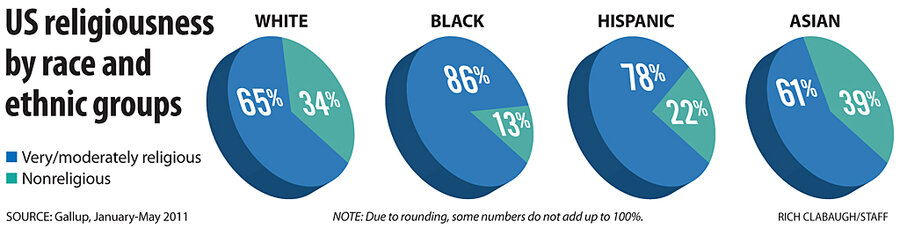

More than anything else, the degree of "religiosity" now seems to divide voters, says Professor Green. People who are very religiously observant – those who go to worship services, read theScriptures, pray – tend to be Republicans. Secular people, along with black Protestants, nonpracticing Jews, and some practicing Catholics, tend to be Democrats. As Hertzke puts it, "Even if you ask about something as simple as grace before meals, you can tell if a person is likely to vote Republican."

Of course, some voters defy categorization, and the campaigns will battle fiercely for them.

Birth control: division or distraction?

Ironically, it's not the red-hot issues of abortion or gay marriage that are clashing with people's rights to practice their own beliefs, but birth control – a big yawn for most Americans. Even for many practicing Catholics, birth control has long been a nonissue, according to the Rev. William Byron, a professor in Philadelphia at both Saint Joseph's University and Villanova University's Center for the Study of Church Management. Studies show birth control isn't often mentioned in confession – suggesting many do not consider it sinful – and is not a reason people give for not going to mass. But even if they're not conflicted by the issue of birth control, Catholics have plenty of interest in Obama's mandate purely on a religious liberties basis.

Pollster Scott Rasmussen says 54 percent of Catholics voted for Obama in 2008, while recent polling shows him getting just 35 percent of the Catholic vote if he runs against Romney this year.

"They either don't like government medicine, or they think the Obama administration wants to pick a fight with the church," observes Mr. Rasmussen.

As religious groups together raised the religious liberties flag over the birth control insurance mandate, former Arkansas Gov. Mike Huckabee told an audience at the February Conservative Political Action Conference: "In many ways, thanks to President Obama, we are all Catholics now."

Churches have responded, some fiercely, to the contraceptive insurance mandate, warning that such a state encroachment on fundamental liberties sets a bad precedent: Swing at Catholics today, your own beliefs may be teed up tomorrow. And they wonder what is to be gained. While the left struggles to reframe the issue as one of women's rights, the right points out that birth control products are available easily and relatively cheaply without anyone's conscience rights being impinged.

Southern Baptists disagree with the Catholic Church on birth control but support the conscience concerns about religious liberties.

"It's [a matter of] religious liberty, not contraception," says Richard Land, president of the Ethics and Religious Liberty Commission of the Southern Baptist Convention. He considers the free birth control the administration offered employees of Catholic institutions in response to the firestorm of opposition insulting. "As one leading Catholic bishop said to me, 'How do we trust [the president] after this? He's taken off his mask.' "

"Religious freedom is a big deal for a lot of religions right now," says Jessica Moody, spokeswoman for the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. In a January statement, her church warned that the recent developments in health care and gay rights threaten the freedom of conscience churches once took for granted in managing their institutions without reprimand or coercion. It quoted founder Joseph Smith on the topic: "I am just as ready to die in defending the rights of a [Presbyterian], a Baptist, or a good man of any other denomination; for the same principle which would trample upon the rights of the Latter-day Saints would trample upon the rights of the Roman Catholics, or of any other denomination."

Does Washington 'get' religion?

Obama's challenge to churches suggests that the White House decided to sacrifice some moderate religious voters in hope of making it up among the women's health contingent.

"The fact that Obama miscalculated so badly may signify the declining influence of the Catholic Church," says Father Byron, and indeed, of other religions, say observers. But any such gamble would have pitfalls as well as potential: Though people's real-world consciences may sometimes supplant a certain religious belief – say, about birth control – it hardly means they want to abandon those beliefs, and the values those beliefs symbolize, altogether.

The legislative branch seems to "get" religion more, and there was widespread alarm there at the president's birth control mandate. House Chaplain Patrick J. Conroy, thinks that "members of Congress may be more religiously intentional than the population at large" because of the nature of their work and its consequences.

The Rev. Barry Black, chaplain of the Senate, reports that 42 of the 100 senators – from both sides of the aisle – take the time weekly to attend Bible study or prayer breakfasts. He warns that when a government imposes a standard that blocks be-lievers from practicing their faith "you have a problem. You have to be very, very cautious. That's a slippery slope."

Outgoing Sen. Joseph Lieberman (Ind.) of Connecticut famously made his own accommodations so he could legislate while remaining an observant Jew. He explains that the Founders pointedly said it was "the Creator" – not Thomas Jefferson or a philosophy of enlightenment – who endowed Americans with their constitutional rights, and that they established the government specifically to ensure those rights. "I don't call my rabbi" to ask how to vote, he says, but his faith is one of the important life dimensions that he brings to lawmaking. Part of Genesis 2:15, "and the Lord placed Adam in the garden to tend and protect it...," directly piqued his interest in the environment, he says. He predicts that the courts will ultimately decide on the president's mandate. Legal challenges are already piling up.

Ever since former President Jimmy Carter came on the scene in 1976, unabashedly speaking of his born-again Christianity, candidates have talked faith so much that voters almost expect it of them now, say experts. Democrats in particular have strategized in recent presidential elections to avoid conceding the faith vote entirely to the Republicans. Of course, such strategizing can benefit a candidate or it can backfire. Personal faith is complex and nuanced, laced with individual interpretations and formed by experience. Using Bible verses to sell policy – right or left – strikes some who think the authority of Scripture should be reserved for moments of greater gravity as either not very creative or flat-out manipulative.

The anti-Christian vote

For some, a liberal vote is a vote against religion, and particularly against evangelical Christians, whom they often see as unwelcome interlopers in the political conversation. But Evangelicals – of whom 68 to 78 percent voted Republican in the past three elections, and who make up 25 to 30 percent of the population – have long been politically active, says Barry Hankins, professor of history and church-state studies at Baylor University in Waco, Texas. Evangelicals, he explains, come from the spectrum of denominations that hold a high view of the authority of the Bible. They tend to have had a conversion – or born-again – experience of some kind, and value activism in the culture.

Early in the 20th century – until liberal Protestantism took hold in the 1930s – Evangelicals actively championed such causes as prison reform, antislavery, and women's rights. When in 1976 Mr. Carter became the first president since Woodrow Wilson to be openly born-again, their hopes were raised, and then dashed, by his presidency. And 1980 saw the rise of the "religious right" and Ronald Reagan, as Evangelicals and observant Catholics – faiths once hostile to one another – came together on a number of issues, especially abortion.

"Progressive liberal culture came to believe that America had moved beyond [religion]," observes Professor Hankins. Its reemergence led to bigotry and hostile attacks on Evangelicals, he says.

Today, believers left and right are worried about a lot more than abortion and gay marriage.

Many are alarmed that the emerging challenge to religious autonomy has broader implications. For example, on a global scale, some think it may someday thwart their ability to manage church humanitarian efforts in compliance with their own reading of the Scriptures. If churches are pressed to violate their beliefs about gay marriage or abortion, for instance, the poor may have to wait while the churches defend their religion in court. Religious groups raise many billions of dollars annually from members and funnel it into virtually every corner of the globe, alleviating poverty, illuminating abuses like human trafficking, and treating disease, says Hertzke. Their style might well be the opposite of the government's – lean budgets, local expertise, working cooperatively and almost unnoticed.

"Especially on the international front, religious groups are important players. They are the largest global [relief] networks in some of the most impoverished places on earth," Hertzke says. "It will be unfortunate for religious liberties," he says, if in the current debate "churches are perceived as a little backward on gender issues.... It doesn't have the front page bite of abortion or gay marriage, but [this work is something] everyone can be in favor of."

Economic conditions will influence the vote for many this fall, as will deep concerns about the responsibility for – and what some believers would call the immorality of – the $16 trillion debt, which balloons to as high as $120 trillion with liabilities like Social Security. "Unfathomable," pollster Rasmussen calls it.

Ultimately, the big question is "Whom do you trust?" – or possibly, "Whom don't you trust?" – with your freedoms. Are you a "government which governs best governs least" sort? Or do you wonder where we'd be today without F.D.R.? Over the years, there have been conservative Democrats and moderate Republicans, but today each side's signature issues seem more firm, and the sides seem increasingly unable to work together. Politicians exploit the divisions, rhetoric escalates, and with candidates in constant campaign mode, voters can tend to see themselves in mortal combat with fellow citizens. The result, say observers: Long-term problems don't get addressed.

Even as the administration works on new fixes to the health-care mandate, religious groups seem more opposed than ever to what they see as a slice-and-dice approach to religious liberties. Fearing that the next chapters of "Obamacare" could tinker with even more fiercely held religious beliefs – abortion, for example – they train their sights on securing the conscience rights of all believers, not just those of religious institutions. A coalition of religious and secular groups – mostly in the antiabortion camp – held religious freedom rallies around the country on March 23.

Rasmussen predicts that the president will attempt to "walk back" his stance on contraception before the presidential race is over, but that its memory will remain, second only to the economy in voter concern this fall.

But he calls this religiously tinged controversy "the key issue if the election is close."