America's big wealth gap: Is it good, bad, or irrelevant?

Loading...

| Boston

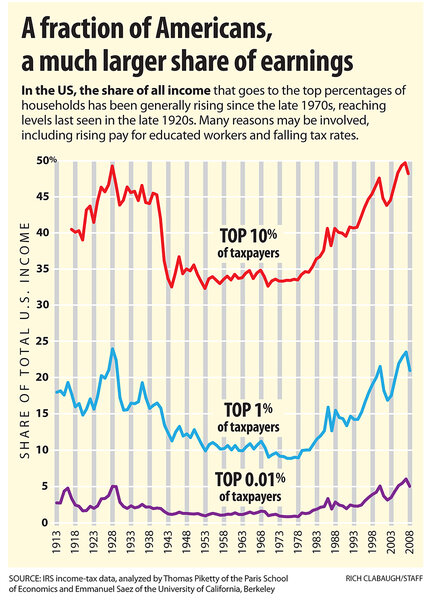

Not since the Roaring '20s has the income gap between rich and poor been as wide as it is today in America – a development that has set politicians, various advocates, and average citizens debating if and why it matters.

President Obama, revving up for a reelection campaign, decries the wealth gap as fundamentally unfair. It's one reason his economic strategy calls for higher taxes on the wealthy.

On the Republican side, presidential hopeful Mitt Romney is seeking to fend off criticism that his wealth and some of his public comments show him to be out of touch with Main Street America. Those rising to his defense celebrate his wealth as just reward for hard work and business savvy – the very qualities the nation itself needs, they say, to get the economy going again.

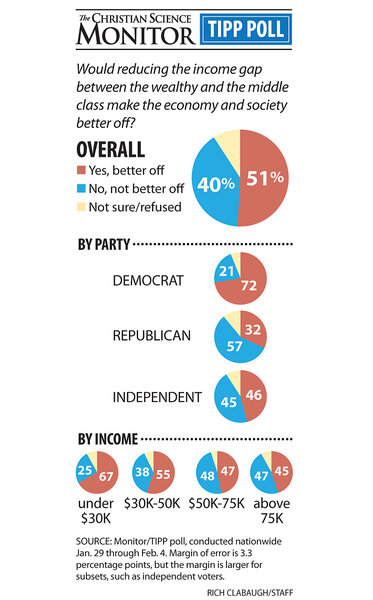

As for the American public, considerable consternation exists from Peoria to Dodge about how pronounced the rich-poor gap has become. In a recent Christian Science Monitor/TIPP poll, 3 in 4 US adults describe themselves as "concerned" about it, and 51 percent say they believe that reducing income inequality would make the economy and society better off.

Are they right to be concerned? Is there something inherently dangerous – to economic health or to the fabric of society – when the income gap gets this wide? Economists have studied such questions for decades, and today the preponderance of evidence tilts toward the view that extreme inequality does hinder, to some debatable degree, economic strength and social stability.

"The view that income inequality harms growth – or that improved equality can help sustain growth – has become more widely held in recent years," World Bank economist Branko Milanovic said in a September report. Not that long ago "the reverse position – that inequality is good for growth – held sway among economists."

That conclusion is by no means settled, and this article will lay out the best arguments of both sides – some of those arguments voiced by ordinary Americans. But what now seems established is that income disparity has risen in recent years within the United States, as well as within other economically advanced nations.

An overview for the US: Over the past three decades, average incomes have grown for typical households at all parts of the earnings scale, but earnings have truly soared for the rich.

Average income for a household in the top 1 percent has more than tripled, from $350,000 in 1979 to $1.3 million in 2007, according to data tracked by Lane Kenworthy, a University of Arizona sociologist drawing on numbers crunched by the Congressional Budget Office. These figures are adjusted for inflation and look at household income after taxes and any transfer payments from the government.

By comparison during those three decades, households in the middle 60 percent saw average real income go from $44,000 to $57,000. For the bottom 20 percent, this gauge shows average household income rising from $15,500 to $17,500.

President Obama has pitched a "fair share" approach to the economy as a central part of his re-election campaign. In his newly released budget, the president proposes, for example, that investment dividends be taxed at the same rate as wage income for high earners. And he argues that, down the road, one principle of tax-code reform should be that the very rich pay at least 30 percent of their income in federal taxes.

The US tax code is an inevitable part of any public debate over issues related to inequality and economic fairness. But economists say past tax policies, which have allowed the wealthy to keep more of their income, aren't the only reason that income gaps have widened.

Other factors that may be at play include an increasingly high-tech economy, which has put a premium on skills and education. Also, whether because of market forces or the policy climate, a rising share of national income has been going to corporations (as profits), while the portion that goes to pay workers has declined. That shift benefits owners of corporate stock.

So long as a boom time kept most people's financial fortunes on the rise, few jumped up and down over the greater concentration of wealth in fewer hands. But the hard times that ensued after the financial system's near-collapse in 2008 have changed that. It's much more top of mind now that the share of people officially deemed to be living in poverty has jumped from about 12.5 percent to 15 percent since 2007, wages are barely rising for the middle class, and many millions more people are out of work.

America has seen the income gap widen before. Often, when class differences moved to center stage, the result has been a political realignment that tilted power and policy at least modestly away from the rich and big business. The 1930s and, before that, the Progressive Era in the early 1900s are prime examples.

But for every individual who is wringing his or her hands over income inequality, there's someone who sees it as the American way.

"You'll make money according to what you've done in life," and according to your education and skills, says Paula Alibrandi, who works as an executive assistant in Boston. "That's only right."

Here's a look at the key arguments:

It's bad for the economy

Nick Hanauer isn't the person you'd expect to be vocal in the fight against inequality. He does venture capital deals as a founder of the firm Second Avenue Partners in Seattle. He's part of that top 1 percent, not one of the so-called 99 percenters involved in various "Occupy" protests in recent months.

But as he sees it, the widening of inequality has created an unhealthy economy, even for people like him.

"If you have a society where the people at the very tippy top accumulate all of the resources, you choke the economy to death," he says.

Mr. Hanauer says that investors and entrepreneurs like himself play an important role in job creation, but that the ability of the middle class to buy products is even more crucial.

"Steve Jobs didn't launch the iPhone in Bangladesh or the Congo. The iPhone is nothing without millions of people who can afford to buy it," says Hanauer, who has recently co-authored a political-economy book called "Gardens of Democracy."

Many economists, to greater or lesser extents, support Hanauer's general point: that a more balanced distribution of income would probably help economic growth.

If the share of earnings going toward pay for labor (as opposed to corporate profits) had held constant in recent years, then overall activity in the economy "would be a bit higher than it is now," says Nigel Gault, chief US economist at the forecasting firm IHS Global Insight in Lexington, Mass.

Inequality may be affecting growth in other ways, Mr. Gault adds. Disparities of income can mean that people lose faith that there's a fair economic playing field and that hard work will pay off. It can also mean that millions of people lack access to a good education. To the degree that these negative forces are operating, America is failing to tap the potential of its "human capital."

Wesley Pointjour, who is getting a degree in business management, will soon be testing the market for his own human capital. The resident of Cambridge, Mass., says he's optimistic that he'll find work when he graduates in May. [Editor's note: Mr. Pointjour's name was misspelled in the original version.]

At the same time, he sees ways that inequality may be hindering the economy.

"Obama's address the other night, that was big," Mr. Pointjour says. "He spoke about being fair and how to ... get the economy flowing again."

The definition of "fair" may depend on individual vantage points, Pointjour allows. But he says that better schools, for instance, might make a difference for people who grow up in lower-income neighborhoods, as he did.

Mr. Milanovic of the World Bank sees this point about education as an important reason that more economists are viewing inequality as bad for growth. "When physical capital mattered most, savings and investments were key," he writes. "[Now] widespread education has become the secret to growth. And broadly accessible education is difficult to achieve unless a society has a relatively even income distribution."

It's bad for US society and politics

To Ben Guaraldi, who teaches computer programming in Cambridge, Mass., America's income divide hits home first and foremost in the political system, as wealthy people and corporations wield an outsize amount of power.

"Some of them aren't really aware of the effects" of the policies they push for, he says. To Mr. Guaraldi, a registered independent, the unfavorable results may include a weaker economy and poorer policies on other fronts, as politicians feel pressure to serve the interests of their financial backers. He, for one, hopes to see stronger government action to confront the threat of climate change.

Many Americans, even ones with very different political leanings, echo that view about money in politics. The rising power of corporations and the rich, coupled with the weak economy, has coincided with an erosion of public trust in governing institutions like Congress and the Federal Reserve.

Some thinkers even say America's very survival is at risk, if steps aren't taken to restrain the widening income divisions. Bruce Judson of the Yale Entrepreneurial Institute has estimated that the US is partway down a path of economic polarization that, based on patterns seen throughout history, could lead the country toward dissolution and revolution. He's not predicting that outcome, but asserts that the scenario is not as far-fetched as it may sound.

Some experts who study inequality argue that it has contributed to a range of damaging social problems. British scholar Richard Wilkinson has pointed to strong correlations between the level of inequality in advanced nations and certain health problems, a decline in trust of others, and higher rates of imprisonment.

It's not holding America back

For most Americans, the big economic priority for government to address is job growth. And among people who care about that, many aren't sure if measures aimed at reducing inequality will help.

Luis Tello, a young Bostonian who works in network marketing, says the economy will do better if people "think abundantly," which will help them see opportunities, rather than focus on who is getting how much.

His theme is similar to what Rabbi Aryeh Spero argued in a recent column for The Wall Street Journal: that US prosperity is built on biblical teachings that enshrine personal property as well as compassion, and that make envy a sin.

A range of other arguments surface for why Americans shouldn't focus too much on inequality.

Some economists argue that misguided efforts to fix it, such as with programs that end up expanding the welfare state, might slow long-term growth.

Others, while saying inequality matters for society, don't believe it's holding back job growth in a significant way. "It's a bad thing, but is it [a] linchpin for economic success?" asks Stephen Rose, a Georgetown University economist who has studied the health of the middle class. "I don't think this [inequality] means we can never have a low unemployment rate again."

Skeptics also question whether inequality is a threat to political and social stability. American democracy, after all, has shown resilience despite ups and downs of inequality in the past. And some researchers say the great class divide is not really about income distribution.

On the political right, author Charles Murray has stirred this discussion with a new book called "Coming Apart." He sees a sharply divided America, with a faltering working class and an out-of-touch elite, but argues that the core issues are all about social behaviors such as churchgoing and community involvement.

Republican presidential candidate Rick Santorum emphasizes some similar themes. For example, he argues that the economy will get back to full strength only if Americans can revive their family-and-community ethic, as well as their work ethic.

Where many free-market advocates emphasize the virtues of individualism, Mr. Santorum has hammered a different message on the campaign trail: "America is about more than just you. America's about service and sacrifice ... making a contribution to the greater good." Talking with voters in Iowa, he said, "When the family breaks down, America doesn't survive."

Santorum's words are just one of the reminders, from left and right, that the income gap is just part of a larger web of economic and social challenges. Even so, it promises to remain a source of hot debate between now and the November election.