9/11 lessons not learned: three failed reforms

Loading...

| Washington

Created by Congress in late 2002, the 9/11 commission was mandated to prepare a full and complete account of the circumstances surrounding the September 11, 2001, terrorist attacks and to provide recommendations designed to guard against future attacks.

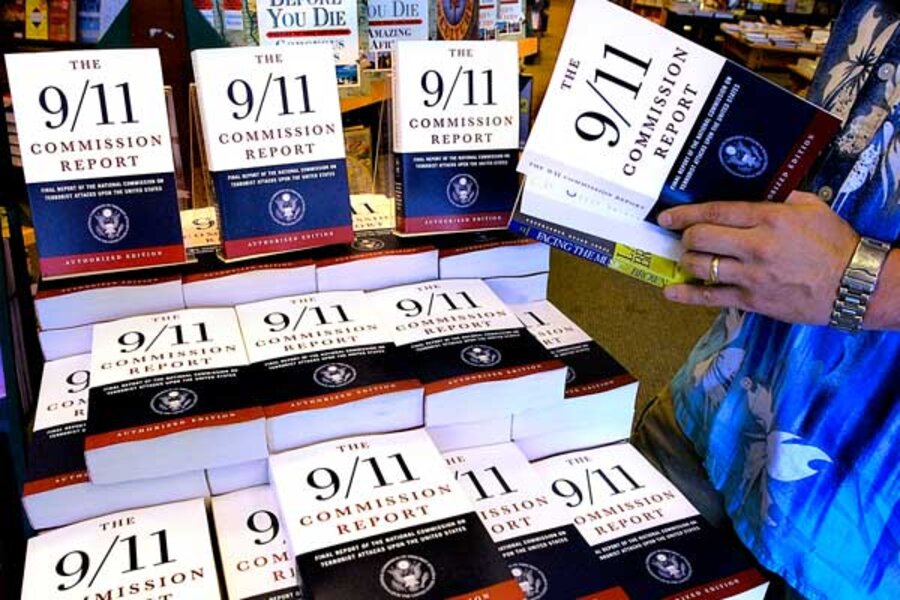

The resulting 9/11 commission report produced a rarity in public life – a government report that's also a bestseller. More than 6 million people downloaded the final report, and another 1.5 million purchased W. W. Norton’s authorized edition, reissued Aug. 8.

The events of 9/11, along with strong pressure from families of the victims, gave the 9/11 commission’s final report, released on July 22, 2004, powerful momentum. Despite a highly polarized campaign cycle, the 9/11 commission’s recommendations were endorsed by both leading presidential candidates and most members of Congress. Most of its 41 recommendations became law or were implemented by executive order.

But now, 10 years after the attacks, significant gaps in carrying out the recommendations remain. Here are three reforms that, though widely supported, have languished in Congress:

Homeland Security too unwieldy

The 9/11 commissioners called on Congress to create a single, principal point of oversight for homeland security to avoid a massive, often duplicative reporting burden. Today, 108 committees oversee homeland security – up from 88 when the 9/11 commission declared the system “dysfunctional.”

“Few things are more difficult to change in Washington than congressional committee jurisdiction and prerogatives,” the report concluded. “The American people may have to insist that these changes occur, or they may well not happen.” Such has been the case.

Since January, the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) has provided more than 1,800 briefings to congressional committees and subcommittees and testified at 120 hearings. From 2008 to 2010, DHS witnesses prepared 4,072 briefings and testified at 304 hearings.

“It’s the one 9/11 commission recommendation there has been no action on,” Homeland Security Secretary Janet Napolitano said at a Monitor breakfast for reporters on Aug. 30. Secretary Napolitano, who has testified before Congress 22 times, said, “And we can’t control the action except to say: Look, if you want to prioritize for us how best we spend our time and resources, Congress looking at itself and the demands it puts on us would be very helpful.”

Special communications for responders

The failure of police and firefighters to communicate added to the death toll on 9/11, especially among first responders. The 9/11 commission recommended that Congress immediately pass pending legislation to assign radio spectrum for public safety purposes. The legislation is still pending.

In February, President Obama called for $10.7 billion effort to help deploy a national wireless broadband network, including a band of radio spectrum (the D-block) to be set aside for emergency responders. Draft bills are pending in both the House and Senate.

In a recent report card on the 9/11 commission’s recommendations, co-chairs Thomas Kean and Lee Hamilton attributed the delay to “a political fight” over whether the D-block should be allocated directly to public safety or auctioned off to a commercial wireless bidder required to give priority access to public safety during emergencies.

But after the ravages of hurricane Irene, along with the Virginia earthquake and devastating Texas wildfires, public safety groups have stepped up calls for Congress to act.

“As a public safety communications director in coastal Virginia, I can assure you that [the] earthquake and hurricane provide too many real-life examples of why public safety needs this dedicated, nationwide broadband network, and with all due respect to our colleagues in the commercial sector, why our nation’s day-to-day and critical emergency communications cannot rely on the commercial network infrastructure,” Terry Hall, first vice president of the Association of Public-Safety Communications Officials (APCO) said in a statement on Sept. 1.

Intelligence czar impotent

Like many blue-ribbon panels before it, the 9/11 commission proposed integrating the vast US intelligence community. The centerpiece of that reform was to be the creation of a director of national intelligence (DNI), charged with managing the nation’s intelligence program and overseeing the 16 intelligence agencies that produce it. The DNI was to have budget authority, as well as the capacity to hire or fire senior managers and set communitywide standards. Housed in the executive office of the White House with a “relatively small staff,” the DNI would report directly to the president.

After resistance from lawmakers close to the Pentagon, Congress opted to leave the budget for most of the intelligence community in the hands of the secretary of Defense. In effect, Congress created the office, but declined to give it the budget or personnel authority to operate it – a decision that may account for why four DNIs have held the office in only six years.

The last DNI, retired Adm. Dennis Blair, stepped down after unusually public clashes with then-CIA Director Leon Panetta and White House counterterrorism chief John Brennan. The current DNI, former Pentagon intelligence chief Lt. Gen. James Clapper is nearly invisible, but for widely reported gaffes in appearances before congressional panels.

Moreover, the DNI operation evolved into a new bureaucracy of its own, with more than 600 employees. "Creation of the DNI did not consolidate the intelligence community and bring different agencies in it together," writes former senior US intelligence official Paul Pillar in his new book, "Intelligence and US Foreign Policy: Iraq, 9/11, and Misguided Reform." "Instead, it created yet another agency, called the Office of the Director of National Intelligence, to sit precariously on top of the other agencies in the community."

“It still is not clear, however, that the DNI is the driving force for intelligence community integration that we had envisioned,” said Kean and Hamilton in their Tenth Anniversary Report Card for the Bipartisan Policy Group, released in September. At $80 billion, the Intelligence Community’s budget is now more than double what it was at the time of the 9/11 attacks.

“We are also concerned that there have been four DNIs in six years. Short tenures detract from the goals of building strong authority in the office and the confidence essential for the president to rely on the DNI as his chief intelligence advisor,” they added.

[ Video is no longer available. ]