Libya intervention: Tea party and liberal Democrats make unusual allies

Loading...

| Washington

Since the first US and allied bombers hit targets in Libya early Sunday morning, the rare voices of protest from Capitol Hill have been coming from a handful of lawmakers on the libertarian right wing of the Republican Party or the antiwar left of the Democratic Party.

These caucuses are ideological bookends on the hot-button fiscal and social issues currently before the Congress. While not meeting formally, they have found common ground in opposition to directing US military firepower in Libya without explicit authorization from Congress.

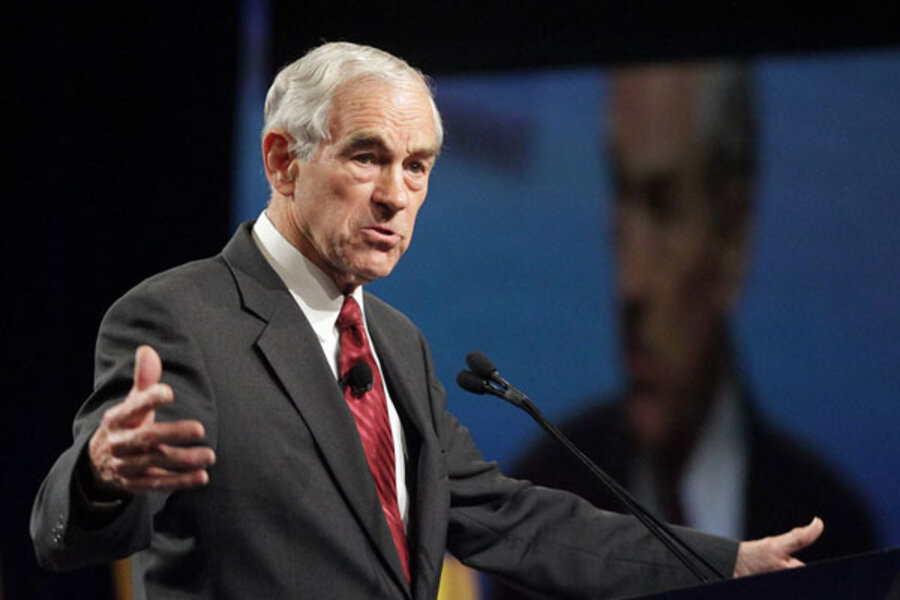

“Imposing a no-fly zone over a country is an act of war,” said Rep. Ron Paul (R) of Texas, noting that the air war over Libya occurred on the anniversary of the US attack on Iraq. Like Iraq, “this could go on for a long time,” despite White House claims to the contrary, he added.

On the left, Rep. Dennis Kucinich (D) of Ohio said: “War from the air is still war,” and called on Congress to be called back into session immediately to decide whether or not to authorize the United States’ participation in a military strike. “Article 1, Section 8 of the Constitution clearly states that the United States Congress has the power to declare war. The president does not. That was the founders’ intent.”

Many in the 87-member Republican freshman class campaigned to rein in the federal role and limit all legislation to what is strictly defined by the US Constitution. But so far, few even in that class have taken a stand to demand a more robust congressional approval of US military actions in Libya.

“It's not enough for the President simply to explain military actions in Libya to the American people, after the fact, as though we are serfs,” said freshman Rep. Justin Amash (R) of Michigan in a Facebook post. “When there is no imminent threat to our country, he cannot launch strikes without authorization from the American people, through our elected Representatives in Congress. No United Nations resolution or congressional act permits the President to circumvent the Constitution,” he added.

Robert Byrd's relentless floor speeches

Congress has been famously reluctant to take on executive war powers since World War II and the Vietnam War era. In the run-up to the Iraq war, the late Sen. Robert Byrd (D) of West Virginia delivered relentless floor speeches to his colleagues of the importance of congressional war powers. Since then, few lawmakers have fought for congressional war powers, especially in the face of a president of their own party.

“The only way you get authority under our Constitution [to go to war] is from the Congress,” says Louis Fisher, who recently retired after four decades at the Library of Congress as senior specialist in separation of powers. Responding to congressional claims that the United Nations or NATO can legitimate the use of US force in Libya, he added: “President and the Congress through the treaty process cannot give away congressional power.”

“The framers knew the last thing anybody would want is an executive who would go to war unilaterally because they had watched countries suffer so much from countries getting involved in horrible wars. War had to be authorized by the country’s representatives,” he added.

On March 17, 8 Republicans and 85 Democrats voted to assert congressional power to order US forces out of Afghanistan. The measure failed, 93 to 321, with Congressman Amash voting “present.”

Two-term Rep. Jason Chaffetz of Utah, one of the eight Republicans voting for the measure, was also one of the first members of Congress to object to a US military role in Libya. “I disagree with the use of US force in Libya,” he said in a Facebook post on March 19. “Projection of US force should be used to combat a clear and present danger to the United States of America. In this case, I see none.”

“There is a problem that members of Congress don’t want the responsibility of making decisions about war and peace,” says David Boaz, executive vice president of the Cato Institute, a libertarian think tank. “It is partly that presidents arrogate to themselves the power to make these life and death decisions, but it is also the case that Congress lets them.”

So far, top lawmakers have limited themselves to requests for a more detailed explanation of the mission, some noting regret that President Obama did not take action sooner to protect Libyan civilians.

In a hearing of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee last Thursday, the chairman, Sen. John Kerry (D) of Massachusetts, urged the Obama administration to heed the “new Arab awakening,” the Arab League’s call for a United Nations no-fly zone, and “seize the moment and recognize the opportunity it presents.”

Since the attacks, congressional leaders on both sides of the aisle have emphasized the need to limit the scope of the US role in Libya. “With the full and unprecedented backing of the Arab League and the United Nations, US forces, along with our allies, are enforcing a no-fly zone over Libya. I support this limited, international action,” said Sen. Richard Durbin, assistant majority leader and a member of the foreign relations panel. “I also agree with President Obama; no US ground forces should be used in this operation and it must remain limited in scope and duration.”

Ensuring limited scope

At issue for House Republican leaders, who so far are speaking with one voice on this issue, is ensuring that the scope and purpose of the mission remain limited. "The president is the commander-in-chief, but the administration has a responsibility to define for the American people, the Congress, and our troops what the mission in Libya is, better explain what America’s role is in achieving that mission, and make clear how it will be accomplished," said Speaker John Boehner (R) of Ohio, in a statement on March 20.

“The speaker supports the efforts of our troops, but this administration must do a better job of communicating to the American people and to Congress about the scope and purpose of our mission in Libya, America’s role, and how it will be achieved,” said Boehner spokesman Michael Steel, in an e-mail.

Rep. Ileana Ros-Lehtinen (R) of Florida, who chairs the House Foreign Affairs Committee, called on the president to “clearly define for the American people what vital United States security interests he believes are currently at stake in Libya.” “Deferring to the United Nations and calling on our military personnel to enforce the 'writ of the international community' sets a dangerous precedent,” she said in a statement.

On the Senate side, Sen. Richard Lugar (R) of Indiana had called for a declaration of war by the Congress before any military action in Libya. Failing that, the president now needs to clarify the mission. “Now, the president has been very clear; no American boots on the ground, no ground troops, no American aircraft over Libya. … But we really have not discovered who it is in Libya that we are trying to support,” he said on CBS’ “Face the Nation.”