Congress's early task: What to do about national debt ceiling?

Loading...

| Washington

Congress returns to a massive agenda in the new year – healthcare, a job-creation plan, financial regulation, global warming, and probes of the Christmas Day bombing attempt. But its first order of business is making sure the government can pay its bills.

Unlike state and local governments, Washington can print money. Problem solved? Not likely. Thanks to war-bond legislation in 1917, Congress has to set a statutory limit for the national debt and must vote to raise it before that limit is exceeded.

Since 1917, it’s been one of the toughest votes on Capitol Hill, because it tends to cast the majority party as a reckless spender.

“Debt ceilings have become political footballs and will continue to be in this highly politicized Congress, where making the other side lose is more important than governing,” says Stanley Collender, a longtime congressional budget analyst at Qorvis Communications in Washington.

A steady rise for the debt limit

In 1995, newly empowered House Republicans pushed the Clinton administration to two government shutdowns over a vote to raise the debt limit. The GOP majority backed down in 1996 and voted to raise the federal debt limit to a then-whopping $5.5 trillion.

With Republican support, President Bush raised the debt limit by more than $6.4 trillion in his eight years in office. Since July 2008, Congress has bumped up the limit by more than $2.5 trillion, mainly to fund programs to deal with the financial crisis.

As the national debt closed in on the new $12.104 trillion ceiling, the House last April voted to increase the limit by $925 billion, to $13.029 trillion. But the Senate couldn’t come up with 60 votes to allow that increase. So Congress passed a $290 billion short-term fix to raise the federal debt ceiling to $12.394 trillion. The measure was approved with 218 votes in the House and 60 in the Senate – the barest of minimums required to pass major legislation. Thirty-nine House Republicans and one Democratic senator, Evan Bayh of Indiana, opposed the measure. One Republican senator, George Voinovich of Ohio, broke ranks to vote with Democrats to raise the debt limit. Senator Voinovich, who is retiring from the Senate at the end of the year, met with President Obama in the White House Tuesday to discuss prospects in Congress for a bipartisan commission to help rein in federal deficits.

With the short-term fix, the Treasury Department projects that the government will run out of funds in February. Because neither party wants to repeat a career-busting government shutdown, a longer-term debt increase appears to be only a matter of time.

A vote to watch on Jan. 20

But the debate and vote, expected on Jan. 20, give both sides a chance to test support for plans to lower federal budget deficits. Such plans are likely to factor in the 2010 midterm elections.

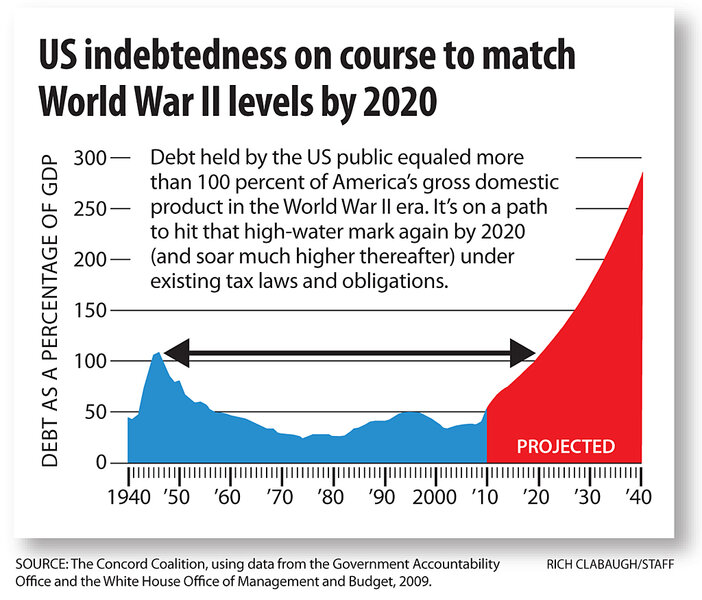

“Congress has no choice but to raise the debt limit, but the fact that they have to take a vote on it does allow a debate on where we are and where we’re headed,” says Robert Bixby, executive director of the Concord Coalition, a public-interest group in Arlington, Va., that calls for lower deficits.

“We’re moving into a period of high attention to deficits, similar to 1992 – the only year when deficit reduction was a big issue in a presidential campaign,” Mr. Bixby adds. “Given the importance of independent voters, Democrats realize they have to show some progress on the deficit or there will be a problem.”

It’s a tough call for Democratic leaders. They had hoped to avoid taking up the issue close to the midterm elections. But they also didn’t want an earlier vote on the issue to be a distraction from endgame negotiations over an overhaul of the US healthcare system.

Yet Republicans have seized on that overhaul as a prime example of big federal spending. Healthcare reform, they say, is a government power grab that America can ill afford, especially given the unsustainable rise in federal deficits.

Quest for a fiscal reform measure

Typically, proposals for a significant hike in the debt limit are accompanied by fiscal reforms. In October 2009, 10 moderates in the Senate’s Democratic caucus, concerned about the ongoing surge of new debt on their watch, warned majority leader Harry Reid that they could not back an increase in the debt ceiling unless a commission or reform procedure was enacted to rein in the debt. Their plan: to vote on an amendment to the debt-limit measure that would create an 18-member commission. That group would propose debt reductions that would come before Congress for an up-or-down vote – without the possibility of amendments or a filibuster.

“If the United States doesn’t come up soon with a credible plan to restore the federal budget to balance over the next five to 10 years, the danger is very real that a debt crisis could lead to a major weakening of American power,” said Sen. Kent Conrad (D) of North Dakota, who is chairman of the Senate Budget Committee. He is cosponsoring the plan with Sen. Judd Gregg of New Hampshire, the top Republican on the panel. A similar bipartisan proposal is backed by Voinovich, Sen. Dianne Feinstein (D) of California, and Sen. Joseph Lieberman (I) of Connecticut.

But many liberal groups, including unions, see the plan as letting an outside, nonelected group usurp congressional prerogatives. They are urging the Senate to reject this proposed amendment.

Other amendments to the debt-limit measure include a proposal by Sen. John Thune (R) of South Dakota to end the Troubled Asset Relief Program.

On the House side, fiscal conservatives in the Democratic caucus have leveraged a commitment from Speaker Nancy Pelosi to allow a floor vote on a measure that would make current pay-as-you-go rules the law of the land.

----

Follow us on Twitter.