Can antiabortion Catholics support Obama? Some do.

Loading...

Roman Catholics – a sought-after swing vote in several battleground states – are caught up in a charged debate over how to apply the church’s moral teaching to politics.

Like other Americans, Catholics rate the economy as the top issue for this election. But the political debate has once again pushed the contentious issue of abortion to the fore, potentially affecting how some “undecideds” vote. It has also stirred concerns that partisanship on the part of a few church leaders could damage the role of faith in public life.

Four years ago, conservatives helped deliver the Catholic vote to George Bush over fellow-Catholic John Kerry, insisting that an antiabortion stance was a litmus test for the candidates.

Viewing that effort as divisive and narrow, other Catholics have since worked to broaden the political agenda to more fully reflect the church’s social teaching and its emphasis on promoting the common good. They’ve created new organizations, such as Catholics United and Catholics in Alliance for the Common Good, and reached out to ordinary Catholics of every stripe, urging them to consider candidates’ positions on a wide range of societal issues.

“These new groups are moderate voices who are presenting the whole array of Catholic social teaching, and they are having an impact,” says the Rev. Thomas Reese, senior fellow at Woodstock Theological Center at Georgetown University in Washington.

At the same time, the US bishops modified their election guidelines for 2008, presenting a moral framework but emphasizing individual responsibility for “prudent” decisionmaking. Calling abortion “an intrinsic evil” that must be opposed, they nevertheless left the door ajar to voting for a candidate who supports abortion rights. In “Forming Consciences for Faithful Citizenship,” the bishops write: “There may be times when a Catholic who rejects a candidate’s unacceptable position may decide to vote for that candidate for other morally grave reasons.” (They also highlighted fundamental concerns that include war and peace, poverty, healthcare, a living wage, and environmental stewardship.)

Despite this opening, the endorsement of Barack Obama by prominent Catholic Republican Douglas Kmiec, a constitutional law expert at Pepperdine University, came as a great surprise to Catholics. Professor Kmiec, a former legal adviser to Presidents Reagan and George H.W. Bush, has written a controversial book – “Can a Catholic Support Him?” – detailing his rationale for Senator Obama based on the Catholic tradition.

While disagreeing with the Democrat’s abortion-rights position, he sees the candidate as sharing the broader worldview of Catholic social teaching. Kmiec once worked on briefs seeking to overturn Roe v. Wade, but he argues that the commitment to programs that reduce abortions will be more effective than continuing to try to reverse Roe. Even if a reversal were achievable, it would only throw the decision back to the states and abortion would continue, he says.

“It’s an argument that will make sense to Catholics who are pragmatists,” says Father Reese.

Kmiec’s comments immediately got him into trouble. A local priest attacked him in a sermon and refused to give him Communion. (Cardinal Roger Mahony, archbishop of Los Angeles, later called that action indefensible.) Church leaders insist that efforts to overturn Roe continue as well as programs to reduce abortions.

Soon, another prominent antiabortion Catholic lawyer, Nicholas Cafardi of Duquesne University, endorsed Obama. He resigned from the board of Steubenville University owing to negative reaction.

A few conservative bishops have attacked the efforts to broaden the agenda and support abortion-rights candidates. A former St. Louis archbishop, now working in Rome, charged that Democrats risked becoming “a party of death.”

Bishop Joseph Martino of the Scranton Diocese interrupted a church forum to say that abortion was the only issue of concern and that his teaching as the local bishop superseded the US bishops’ guidance. He also threatened to refuse Communion to vice presidential candidate Joseph Biden if he came to Scranton, Pa., where he grew up.

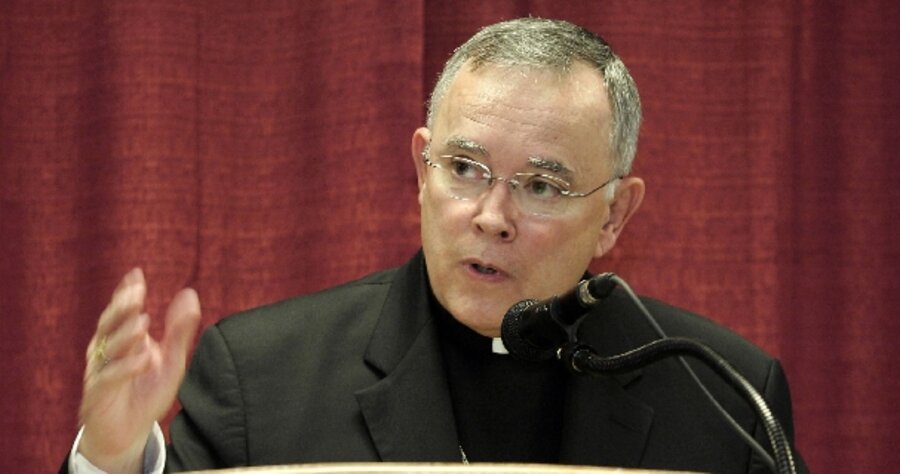

Archbishop Charles Chaput of Denver insisted that Kmiec and groups like Catholics United and Catholics in Alliance “have done a disservice to the Church.”

“Simply put, he has a different prudential judgment about how to apply church teachings to public policy,” says Chris Korzen, who heads Catholics United. “The bishops acknowledge they don’t speak with the same authority on political matters as on moral matters.”

Indeed, church policy says church leaders are to inform the consciences of Catholics but not to instruct them how to vote nor get involved in politics. It’s up to lay Catholics to express those values in political action.

Most bishops are doing their best to stay out of the spotlight during the campaign. Many Catholics, however, would like them to rein in their outspoken colleagues, who they feel have crossed a line into partisanship. Some have called on bishops not to violate their own guidelines.

“A few bishops and prelates have come dangerously close to making implicit political endorsements by telling Catholics that abortion trumps all other moral issues and lashing out against the Democratic party,” writes Lisa Sowle Cahill, professor of theology at Boston College, in the National Catholic Reporter. “When clergy mistake their role as pastors and spiritual teachers by making tacit endorsements, a tenuous line has been crossed.”

At the same time, conservative Catholic Deal Hudson, a Republican adviser, charges that if Obama wins with the help of Catholics, the bishops’ own guidance will be to blame, providing “the escape clauses needed to convince Catholics they could vote for a pro-abortion candidate in ‘good conscience.’ ”

Catholics, who are 25 percent of the US population, have long been pivotal in presidential elections. Since 1972, they’ve chosen Republicans five times and Democrats four times and always sided with the top vote-getter.

This year, conservative and progressive groups have issued competing voting guides, and the two political campaigns are avidly wooing swing voters.

In Pennsylvania, a battleground state, two sets of Catholics fit that category – working-class Democrats from culturally conservative families and well-to-do suburbanites, says G. Terry Madonna, political science professor at Franklin and Marshall College in Lancaster, Pa.

“Catholics are a higher proportion in this state than in others, about 35 percent, and if you win the Catholic vote, you’re likely to win Pennsylvania,” he says, “and the nation.”