US soldiers left Vietnam 50 years ago. How do these nations cooperate now?

Loading...

In the 50 years since it ended, the Vietnam War has reshaped attitudes of soldiers and protesters alike about both the U.S. military and America’s engagement with the world.

This has included prompting reflections about America’s military missions and methods within the Pentagon itself. It was, after all, in part because of protests like the one a young soldier named Rodney Coates undertook – under threat of possible execution – that the U.S. military ended the draft and became an all-volunteer force.

As Americans mark the 50th anniversary of the April 30 withdrawal of the last Americans from Saigon (now Ho Chi Minh City), U.S. diplomats in Vietnam have reportedly been told to avoid commemorating a war America didn’t win and one in which President Donald Trump, using a medical exemption, didn’t fight.

Why We Wrote This

A story focused onIn the 50 years since the Vietnam War ended, America and Vietnam’s efforts at partnership and reconciliation have continued. In some cases, these efforts mirror the war veterans’ journeys as well.

Yet America and Vietnam continue to forge ties.

Investment and trade between the two nations have grown dramatically in the past 25 years, and military ties have also deepened. Funds for some projects that acknowledge some of America’s harmful wartime operations in Vietnam are flowing again after being put on hold during a 90-day evaluation period.

While President Trump’s high tariffs proposed for Vietnam have thrown a wrench into deepening ties, Vietnam continues to view the United States as a critical security counterweight to China, its northern neighbor. How Vietnam handles uncertainty around a U.S. trade war could influence how closely the two countries continue to partner.

Cooperation plays an “essential role in the process of reconciliation and trust-building between the two countries,” the state-run Viet Nam News wrote. That process mirrors the journey of many Vietnam veterans.

College deferments and the call of duty

For Dr. Coates, a young Black soldier in the late 1960s and early ’70s, that journey to reconciliation – even with his own country – began as a college student who had qualified for a coveted academic deferment from the Vietnam draft.

Spending college weekends at home in East St. Louis with his father, a police officer, and his mother, who worked at the local Air Force base, he felt guilty, he says, when he ran into friends being drafted or parents who’d lost a child fighting. With his own family history of military service dating back to the Spanish-American War, he grappled with shame, he says, that he had the “privilege” of attending college and not fighting alongside his peers.

Back on campus at Southern Illinois University, he countered a professor. “He was ranting about why the war was bad, and I, being the obnoxious college student, raised my hand and asked him, ‘So what war did you serve in?’”

The answer was no wars. The young Dr. Coates then accused the professor of being “inauthentic.” He and another classmate “literally got up at that moment, walked out of class, and found our way to the Army recruiting station.”

In Vietnam, his best friend was the New Orleans-born son of a Ku Klux Klan leader. “He would always say, ‘You know, Rodney, you’re my best friend. But you can’t date my sister.’ I’d say, ‘Look, Ralph, I’ve seen a picture of your sister – she’s just as ugly as you are.’ I mean, we were tight.”

The whole unit was tight. Off-duty, they studied the history of Ho Chi Minh, the communist leader of North Vietnam, who had modeled his military campaign of independence from colonial France on George Washington.

Then they decided the American war was immoral and went on strike.

This meant they no longer recorded communications that it was their mission to collect. Their unit commanders called in Dr. Coates and several fellow soldiers and threatened them with court-martial and execution.

But the 200-member unit stuck together. Leadership backed down, quietly dispersing and replacing the troops instead.

Home from Vietnam, the disillusioned soldier became a conscientious objector as he served out his enlistment.

From conflict to reconciliation

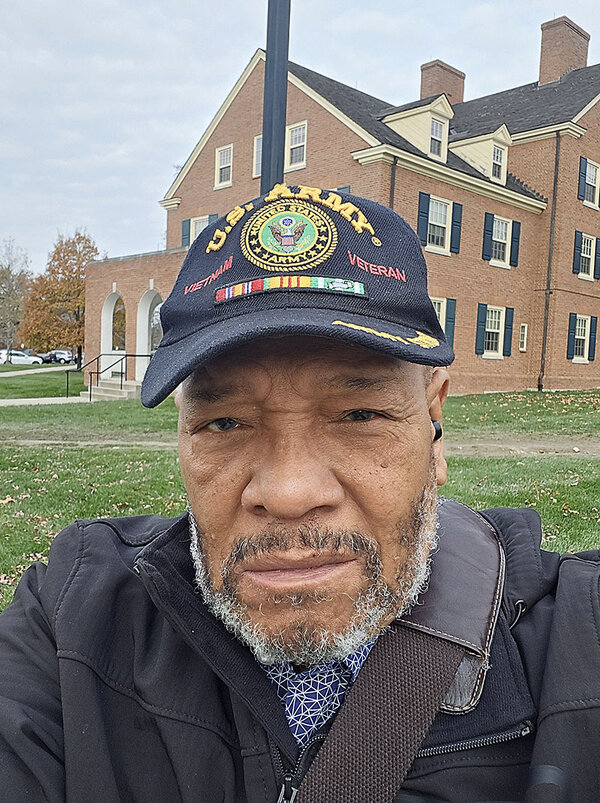

Today, Dr. Coates is a college professor and U.S. Army veteran who takes pride in his military service and appreciates the democracy that allowed him to protest it.

America’s relationship with its former adversary has evolved as well. The U.S. lifted its ban on lethal weapons sales to Vietnam in 2016 and, late last year, for the first time since the war, delivered a “next-generation military” training aircraft to its former adversary.

Washington’s goal “is to ensure that Vietnam has what it needs to defend its interests at sea, in the air, on the ground, and in cyberspace,” U.S. Ambassador to Vietnam Marc Knapper said in December. Tensions in the South China Sea have increased as Vietnam disputes Chinese claims in the strategic waters.

“The Vietnamese people I’ve met in the military, and outside ... want to make a better life for themselves by being able to effectively defend their nation,” says retired Col. Thomas Webster, an executive at Textron Aviation in Kansas, which makes the training aircraft. “We’re very interested to see where this goes.”

There was some doubt about that bilateral trajectory when President Trump issued an executive order shortly after taking office, suspending funds for the U.S. Agency for International Development for projects in Vietnam.

This included U.S. efforts to remove millions of unexploded mines it planted during the war and to remediate the damage of Agent Orange, sprayed to destroy foliage that helped fighters hide, along with projects to improve the lives of those born in areas of chemical contamination.

After a 90-day government review, these projects have largely been reinstated, analysts say, though the future of a widely anticipated exhibit scheduled to open this year at the Reconciliation War Museum in Ho Chi Minh City remains to be seen.

The plan had been for the U.S. and Vietnam to cooperate on a joint exhibit about “overcoming the consequences of war” and “resolving war legacies,” featuring the U.S. de-mining and Agent Orange remediation efforts. It would mark “the first time the U.S. government has a direct say in how events surrounding the Vietnam War are memorialized,” says Tappy Lung, an international relations specialist who researched the topic at the Center for Strategic and International Studies.

A shared experience

As for Dr. Coates, he struggled for years to make sense of his service and the skepticism he encountered within the protest movement upon his return. He decided that sharing his experience, particularly having grown up as a “privileged Black person,” was the point of his teaching as a professor at Miami University in Ohio.

In recent years, a friend who’d long been encouraging Dr. Coates to talk more about the war gave him a “Vietnam veteran” baseball cap and urged him to wear it.

Dr. Coates finally agreed on the same day that he was late for a flight. “The counter lady says, ‘We’ll try to get you on the next one.’” Then she saw his hat.

“She called two of the tallest, thickest white boys from Kentucky” to hustle him to the plane, thanking him for his service along the way. Now he rarely leaves the house without his hat.

“Even shopping, white folks in Southern gear – I mean with rebel flags on their shoulders – send their kids over to say, ‘Thank you, sir, for your service.’”

“It’s a trip,” he says. “I’m proud of what we did, that we challenged this war – and I’m proud of my service.”