Disarray at Pentagon puts spotlight on civilian leadership’s crucial role

Loading...

The exodus of advisers from Secretary of Defense Pete Hegseth’s office is affecting U.S. troops far from the Pentagon – highlighting the importance of strong civilian leadership.

At U.S. bases across the Atlantic Ocean, queries for the secretary and his staff are going unanswered, documents unsigned, and decisions delayed for weeks, including surrounding a large review of the U.S. force presence in Europe, sources say.

“You get a sense of the turmoil in the Pentagon – there’s been no decisions because they’re dealing with staffing issues,” says a senior U.S. military official in Europe, who like some other service members interviewed for this story asked for anonymity to speak candidly.

Why We Wrote This

Many U.S. military officials welcome the idea of rethinking defense policies and posture. But they also say it’s vital in a democracy for direction to be set by the president and the secretary of defense. The worry now is about a leadership vacuum.

These reported backlogs, along with leaks using the platform Signal of “sensitive operational details that we would hold highly classified,” as the official put it, have diminished confidence in the defense secretary among many in uniform.

All this, too, can feed concerns among other nations about U.S. military readiness to respond in a crisis, security experts say.

Perceptions of disarray and of a vacuum of leadership at the Pentagon have grown more urgent in recent days as Secretary Hegseth has fired several close advisers, pushed aside his erstwhile chief of staff, and threatened military advisers with lie detector tests to root out leaks.

As civilian positions are left unfilled, or as people get forced out and fed up, “You don’t get strong advocacy for the president’s agenda,” which in turn feeds suspicions that it’s being thwarted, says retired Col. Todd Schmidt, former editor of the Military Review, the professional journal of the United States Army.

But though members of the military may harbor critiques, officers are often the first to point out that at the policy level, generals are meant to guide, not lead. It’s also not good for democracy, they add, when the U.S. military is forced to fill leadership gaps.

“It’s not our job to be the adults in the room,” the senior military official says. “Our job is to do our level best to be apolitical and to advise.”

Beyond believing in civilian control, many within the U.S. military support the Trump administration’s desire to reform spending, rethink policy, and demand that generals win wars. Many officers also think the country has become too deferential to the armed services for its own good.

“I’d be the first one to tell you that the secretary of defense position needs fresh blood, particularly after being managed by retired generals for so long,” says Jason Dempsey, an Army Ranger who served as special assistant to the chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff.

“I think everyone wants a military where all the policy and direction isn’t dominated by uniformed players. It needs a different perspective,” he adds. “What it didn’t need is for us to go from the perspective of a general to the perspective of a major.”

In President Donald Trump’s first term, the post was held by retired four-star Gen. James Mattis, who was often referred to as the “adult in the room.”

Within ranks, mixed attitudes on Hegseth

The point about Mr. Hegseth being “only” a major comes up a lot among his military critics. One former senior defense official says Mr. Hegseth’s tenure so far reminds him of morale-building programs that reward high-performing junior troops by letting them be “commander for a day.”

They park in the commander’s spot and stand in front of the unit giving orders, which tend to involve making generals do physical training. One of the earliest directives Mr. Hegseth issued was to change the PT test. “That’s what a private does when he’s made commander for a day,” the defense official says. “And our adversaries are watching.”

Others point to the secretary’s posts on the social platform X, including an arch threat this week to put women’s products in military men’s restrooms, which some see as playing into juvenile hypermasculine stereotypes of what a service member should be and distracting from pressing Pentagon policy.

Such criticisms are a sign of resentment among senior ranks suspicious of a new sheriff in town, some say. Others add that they appreciate the Trump administration’s apparent affinity for junior troops.

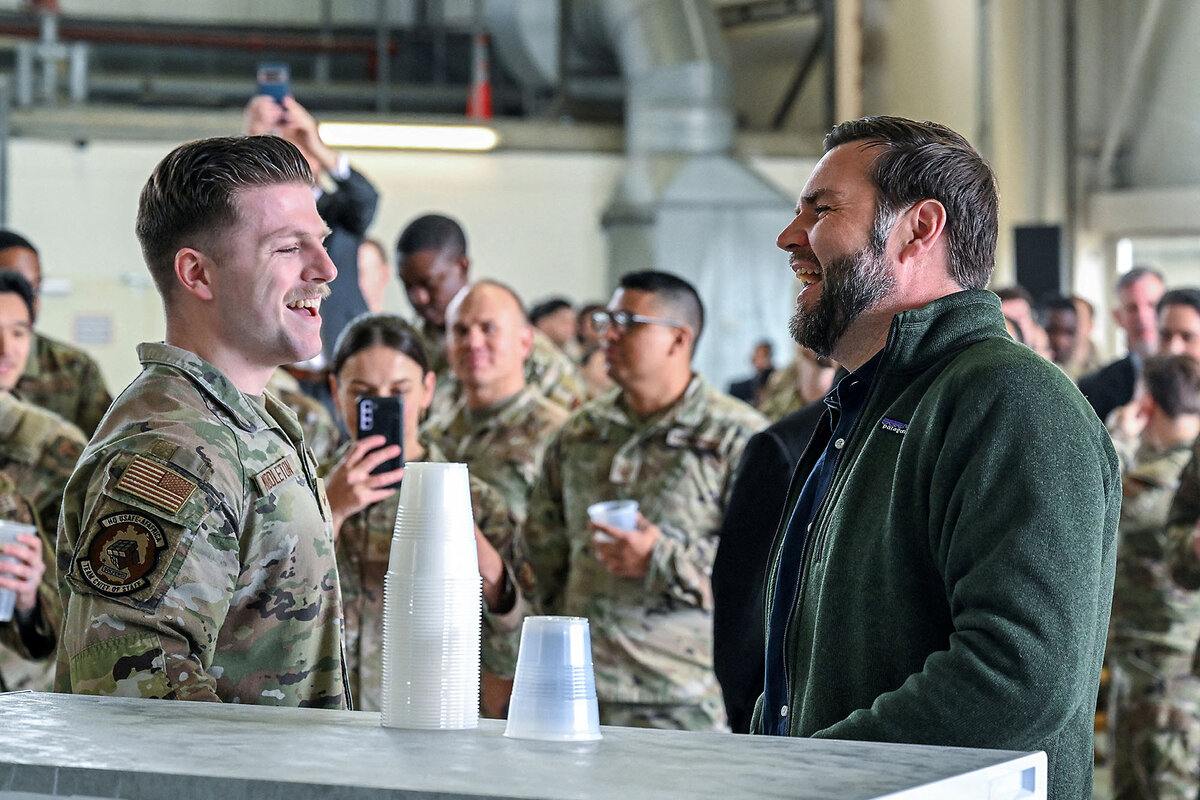

One U.S. military official in Europe marveled that when Vice President JD Vance, who served as a lower-ranking enlisted Marine, visited a base recently, “He was surrounded by these junior Marines who were ecstatic. All of them just kept saying, ‘He’s one of us.’”

The Trump administration is talking about cutting the ranks of top generals by half, a move that would be welcome among many midcareer officers, the U.S. military official adds.

“When you have so many chiefs, they all require a brief,” he says. Fewer generals would mean fewer briefs, quicker decisions, and the empowering of up-and-coming officers. “That’s a good thing.”

At the same time, the “general for a day” anecdotes belie a frustration among military officers who acknowledge a need for reform but see it as misdirected under Mr. Hegseth, says Dr. Dempsey, now an adjunct senior fellow in the Military, Veterans, and Society program at the Center for a New American Security.

“This institution needs a hard look. And there’s this genuine desire, even among veterans and people in the military, for that to happen.” But Mr. Hegseth appears primarily focused on “renaming bases, banning books, and superficial culture-war issues,” he says, rather than what would be a welcome deep dive into the direction of U.S. defense policy.

The need for civilian leadership

Yet while many within the Defense Department crave clear civilian leadership, service members are more likely to see national security as a pressing existential issue because they put their lives and families on the line fighting wars, says Dr. Schmidt, the retired colonel.

And so when they perceive the Pentagon to be disarray, in this or in previous administrations, they quickly try to fill gaps – and, he adds, their power grows.

A serious charge that emerged this week is the accusation by Trump administration officials that the top U.S. commander for the Middle East, Gen. Erik Kurilla, leaked details of Mr. Hegseth’s Signal communications in order to bolster his own policy goals by discrediting the secretary.

The report in question is that Mr. Hegseth discussed sensitive information, including about a planned strike against Houthis, on the platform Signal with his brother, who now works at the Pentagon, and with his wife, who does not. Signal, while encrypted, is not considered secure.

It may also be that military officials leaked to the press because they think the secretary has been careless with operational details that could get their troops killed – while denying it’s a big deal.

These important details aside, for years the civil-military imbalance has been “less about how powerful the military is and more about how broken our political system has become,” Dr. Schmidt says.

Going forward, if lawmakers and civilian leaders in any administration are to confront this dangerous dynamic, “They need to focus less on the military and more on themselves,” he argues.

For now, Mr. Hegseth appears to have the confidence of President Trump. Ultimately, it matters to have a trusted and effective communicator at the helm, says the senior military official in Europe.

“We want a secretary who can make decisions and can advise the president,” he says. “I think everyone in uniform wants every secretary of defense to succeed.”