In Eagle Pass, the border crisis is complicated

Loading...

| Eagle Pass, Texas

Living and working less than 2 miles from the Rio Grande, Margil Lopez is at the heart of the United States’ migrant crisis. Yet it took a trip to the hospital, after his father threw his back out, for him to grasp the scale of the crisis in the small town of Eagle Pass, Texas.

“It took us five hours to even see the doctor,” he says.

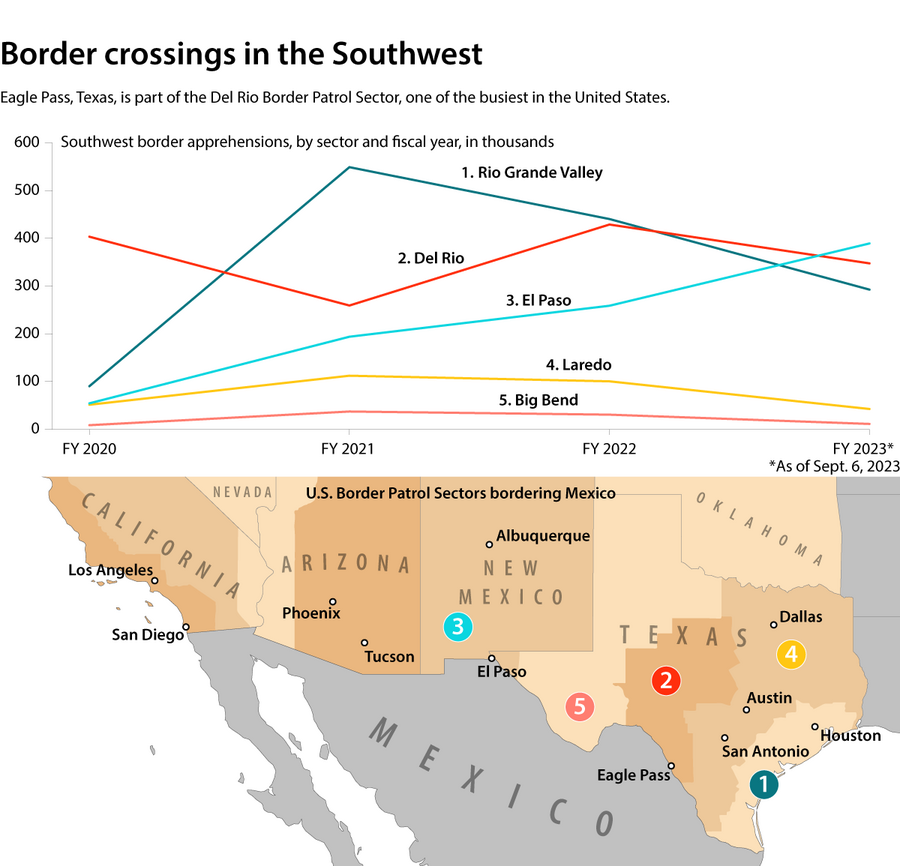

For over a year, this rural sector of the southern border has seen more migrant crossings than almost any other. The Biden administration has been responding with a combination of carrots and sticks, from creating new legal pathways for certain migrants to continuing a policy of rapidly expelling certain other migrants. But the state of Texas has been responding here as well, and with much more aggression.

Why We Wrote This

Residents of Eagle Pass, Texas, live with the border crisis in ways most of the rest of the U.S. does not. They want a secure border. They also want humane treatment of migrants.

In an unprecedented venture into immigration enforcement by a state government, Texas Gov. Greg Abbott, a Republican, launched Operation Lone Star in 2021. The $4.4 billion border security initiative has seen state police and National Guard members – reinforced by National Guard units from other Republican-led states – patrolling the Rio Grande, arresting migrants who trespass on private property, and blockading the river with shipping containers, razor wire, and floating buoys buttressed with nets and saw blades.

Operation Lone Star has been controversial since its inception. Public officials and human rights groups have criticized the initiative as inhumane and unlawful. Some rank-and-file service members have objected to the operation as well. Texas is fighting a federal lawsuit seeking to remove the floating barrier.

Meanwhile, migrants have continued to enter Eagle Pass illegally – and recently they’ve done so in large numbers. Mayor Rolando Salinas issued a disaster declaration last week after thousands of migrants crossed into the city in just two days. “It has taken a toll on our local resources, specifically our police force and our fire department,” he told the San Antonio Express-News.

For Eagle Pass residents, the crisis is provoking a complex range of emotions. Border security is a necessary piece of local law enforcement here, especially in recent years. Many locals, descended from legal immigrants, take umbrage with illegal immigration, and they count U.S. Customs and Border Protection agents as friends, neighbors, and relatives. Businesses have also benefited from the patronage of state police and the National Guard.

At the same time, residents are increasingly alienated by the state-led intervention in the city. Many view the buoy barrier and razor wire as steps too far. Rents have spiked as thousands of personnel have been posted on monthslong deployments, and emergency services that locals rely on are overwhelmed.

“I feel like the investment was pointless,” says Mr. Lopez. “It’s also kind of inhumane.”

The way the crisis is being handled by both the federal and state governments, he adds, “is like releasing a dam and not preparing for the flood of water going in every single direction and how it affects the communities that are at the brunt of it.”

“He asked for water and for Border Patrol”

Earlier this summer, on a 110-degree Fahrenheit day, Raul Riza found a migrant collapsed in his trailer yard about 2 miles from the border.

“He asked for water and for Border Patrol,” he says. And while that encounter may not have been threatening, he often sees migrants knocking on doors in neighborhoods on the edge of town, and he’s heard of migrants breaking into homes.

Thus, Mr. Riza supports what the state has been doing with Operation Lone Star, including busing migrants to the White House and blue cities like New York and Los Angeles. That also includes deploying the buoys and razor wire. Born and raised in Eagle Pass, the manager at a local gym says the federal government hasn’t been doing enough to help the town cope with the huge numbers of migrants on its doorstep.

When former President Donald Trump was in office, “they’d been handling it good,” he adds. Since President Joe Biden replaced him, “it’s just like they opened the gates and let them in.”

With a population just over 28,000 and the local resources to match – Eagle Pass has two hospitals, a police force of about 100 people, and only one migrant shelter – the city isn’t equipped for being the busiest crossing point on the southern border.

And last week saw a spike in migrants, with a reported 9,000 crossing in a week. The sudden surge also caused the Border Patrol to temporarily block vehicle and rail traffic from Mexico into Eagle Pass. The closure of such a vital source of local revenue also motivated the recent disaster declaration.

“Every day the bridge is closed we are losing money,” Mayor Salinas told The New York Times last week.

Late last week, U.S. and Mexican government officials struck an agreement to make new efforts to deter migrants traveling north to the U.S. border. Mexico agreed to deport migrants to their home countries in Latin America – a potentially significant agreement since the U.S. doesn’t have relations with countries many asylum-seekers are fleeing, like Venezuela and Nicaragua – and to more closely monitor migrants using the country’s train system to travel north, CNN reported.

“Migrants themselves, as well as smugglers, change their tactics day by day, hour by hour” at the border, says Doris Meissner, a senior fellow at the Migration Policy Institute.

“The issue of people hopping onto trains and traveling on the tops of trains is just so dangerous and so desperate,” she adds. “If they’re now coming to the table and committing to addressing that, that could be significant.”

“Now everything’s peaceful”

For Jessie Fuentes, reactions to the migrant surge last week have been overblown. Speaking a few days after the disaster declaration had been made, he said the city was quiet again.

“It was a little crazy, but now everything’s peaceful,” he added.

The chaos in Eagle Pass and on this section of the border is as much due to the Texas government as the migrants. For decades, local authorities have had good working relationships with Customs and Border Protection and with Mexican officials. And in Texas’ border cities, Border Patrol is a well-regarded employer and community member.

The involvement of state personnel has upset the status quo in Eagle Pass, says Mr. Fuentes, owner of Epi’s Canoe & Kayak. Border Patrol has been operating in the city for 150 years, “and there’s never been a barrier built. There’s never been mistreatment of individuals like is currently happening,” he adds.

State officials have pointed to arrest and drug-seizure statistics as evidence of the difference Operation Lone Star is making. Through 2022, the initiative has led to over 23,000 criminal arrests and over 21,000 criminal charges, Governor Abbott’s office reported. Those numbers represent just a fraction of the nearly 1.3 million border encounters logged by Border Patrol in Texas in 2022, however.

Yandi Fragela was one of those 1.3 million encounters. A native of Cuba, he says he fled to Nicaragua because of the Castro regime, but then fled to the U.S. because of government repression in Nicaragua.

The journey aged him, he says, with the jet-black hair and goatee he flaunted as a drummer replaced by a shaved head and beard riddled with gray. He’s been saving and gathering materials to apply for a special green card for Cuban citizens, watching the migrant crisis grow worse and worse.

While he understands why so many migrants are trying to enter the U.S., he also understands why authorities here have been responding with some force. He also admits that the buoy barrier is “aggressive,” and has only had the effect of forcing migrants to cross in more dangerous places.

“It’s difficult. I am [an asylum-seeker], but there are too many people crossing,” he says. “Migration is a right for every person, but a country needs to take care of its people, too.”

Who is in charge of the border?

What Texas is doing may not be legal, however. Courts have long held that immigration enforcement is a federal government function, and while border states can enforce state law in border regions, Texas might have taken it too far.

“Texas law enforcement doesn’t have immigration enforcement authority. That’s not going to change. The authority is federal authority,” says Ms. Meissner.

Operation Lone Star “is an enormous commitment of resources and cost for taxpayers in Texas, but it still is considerably more a political statement than it is a law enforcement operation,” she adds.

Rep. Eddie Morales Jr., who represents Eagle Pass in the state Legislature, wants to see the state take a different approach.

In 2021, he was the only Democrat in his chamber to vote to commit nearly $2 billion to state border security initiatives, including Operation Lone Star. His views have changed, however, in part due to revelations like those described by a state trooper in July in an internal email of children and pregnant women getting caught in razor wire and troopers being ordered to push migrants back into the river.

“That’s when I thought we overstepped the line,” he said at the Texas Tribune Festival last weekend.

“We can’t just throw money at this,” he added. Given the limits on state power in immigration matters, “we need to think outside that box.”

In a letter to Governor Abbott last year, he outlined what he would like the state government to help with. Expanding and improving land ports and roads into and around border cities can help boost the already-thriving trade relationship between the U.S. and Mexico; a migrant workforce program can curb the migrant crisis and fill job vacancies statewide.

Across the state, Texans are similarly divided over the state’s activities on the border. A majority of Texas voters support placing buoys and barbed wire at the Rio Grande, according to an August poll by the Texas Politics Project at the University of Texas at Austin, and a majority support deploying additional state police and military resources to the border.

Mr. Lopez says he thinks most Americans are “in the middle” when it comes to the migrant crisis. Yes, there needs to be border security. And yes, migrants need to be treated like human beings.

Meanwhile, the city is in the middle of reinventing itself. Five years ago he returned to Eagle Pass to open a bakery with his sister. It’s one of several new businesses that have opened in recent years. Young people who left for college are returning and taking leadership positions in local arts and business groups. Historic buildings are being restored, and there’s talk of developing a park and walking area to complement a similar park across the bridge in Piedras Negras, Mexico.

“It’s a really cool time to be in Eagle Pass and be involved with the changes that are happening,” Mr. Lopez says. But amid the migrant crisis, the city is also “a mess.”

“Nobody wants to take full accountability,” he adds. “It’s just straining the resources of small little towns along the border.”