‘The time has come’: Which US bases may lose their Confederate namesakes?

Loading...

As the protests around the killings of Breonna Taylor and George Floyd gained momentum, so, too, has a long-standing push in the United States to remove the icons and symbols of the Confederacy. Towns are tearing down statues, and the Confederate flag is increasingly being banned as a symbol of hostility, not heritage.

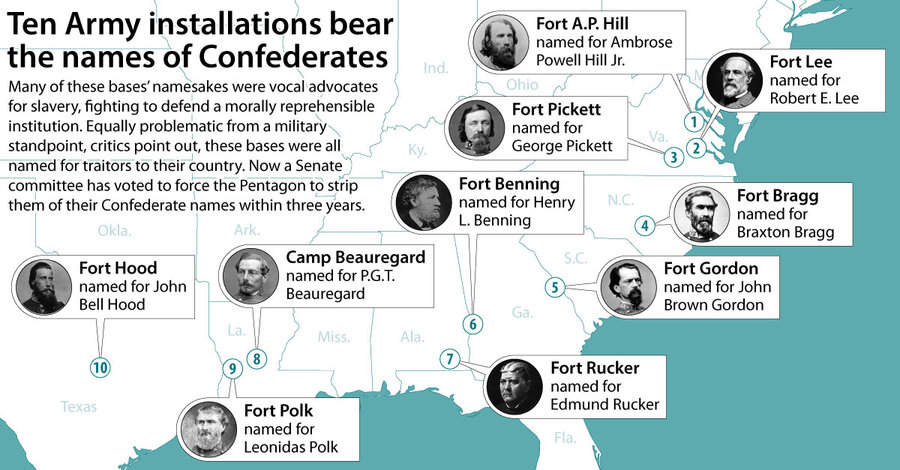

Now a Senate committee has voted to force the Pentagon to strip 10 U.S. military posts of their Confederate names within three years – a move that the Defense Department has resisted for years.

Given the side they chose, many of these bases’ namesakes were vocal advocates for slavery, fighting to defend a morally reprehensible institution. Also problematic from a military standpoint, critics point out, these bases were all named for traitors to their country. Some of those honored were also notoriously bad commanders.

Why We Wrote This

With pressure growing on the U.S. military to strip the names of Confederate officers from its bases, the question arises: Just who were these men, and what were they really known for?

President Donald Trump says he will “not even consider” renaming the bases, calling them “part of a great American heritage.” But decorated modern-day military leaders have pushed back, arguing that it’s the right move.

“The events since the killing of George Floyd present us with an opportunity where we can move forward to change those bases,” former Defense Secretary Robert Gates told The New York Times this week. “It’s always puzzled me that we don’t have a Fort George Washington or a Fort Ulysses S. Grant or a Fort Patton or a facility named for an African American Medal of Honor recipient. I think the time has come, and we have a real opportunity here.”

Here’s a rundown of the bases, and a bit of background on their namesakes:

1. FORT A.P. HILL, Virginia

One of Robert E. Lee’s most trusted subordinates, Ambrose Powell Hill Jr. had a meteoric rise through the ranks, becoming the youngest major general in the Confederate Army. His reputation as a fearless commander and aggressive tactician did not translate into fighting success later in the war, however. Hill died in battle a week before Lee’s surrender at Appomattox, saying he had no desire to see the collapse of the Confederacy.

2. FORT LEE, Virginia

No Civil War general had a pedigree more all-American than Robert E. Lee, a legendarily handsome man known as the “marble model” among his West Point classmates. Two of his ancestors were signers of the Declaration of Independence, and his father, Henry, wrote the famous ode to his good friend George Washington, “First in war, first in peace, first in the hearts of his countrymen,” according to historian Robert Leckie.

But when Lee was approached to lead the Union Army’s 75,000-plus soldiers, he refused, explaining that though he opposed secession, “I could take no part in an invasion of the Southern States.” Instead, he returned to his native Virginia to “share the miseries of my people.” In what was widely considered an act of treason, he took command of the Confederacy’s Army of Northern Virginia, whose troops revered him. “I’ve heard of God,” said one, “but I’ve seen General Lee.”

And while Lee is often portrayed as a benevolent general who happened to own slaves, he saw slavery as a positive institution, once writing in a letter, “The painful discipline [Blacks] are undergoing, is necessary for their instruction as a race, & I hope will prepare & lead them to better things.” He made a point of breaking up Black families on his plantation and administered particularly harsh beatings. And when his army encountered free Black Americans in the field, Lee ordered them enslaved and brought back to the South as property.

3. FORT PICKETT, Virginia

George Pickett, who graduated last in his West Point class, is best known for leading Pickett’s Charge at the Battle of Gettysburg. Of Pickett’s division of 5,500, some 1,100 were wounded, 1,500 were declared missing or captured, and 224 were killed. Pickett’s official battle report was reportedly rejected by his higher-ups for its “bitter negativity.” Asked by journalists why his infamous charge failed, Pickett liked to say, “I’ve always thought the Yankees had something to do with it.” After the war, Pickett fled to Canada for a year, fearing prosecution for his execution of 22 captured soldiers, before Ulysses S. Grant interceded on his behalf.

4. FORT BRAGG, North Carolina

A West Point graduate with a “prickly nature” and a reputation for engendering “cold looks” among his troops, Gen. Braxton Bragg – for whom America’s largest military installation is named – was not a great leader, according to just about all historians, including Earl J. Hess, author of “Braxton Bragg: The Most Hated Man of the Confederacy.” Though he distinguished himself in the Mexican-American War, his leadership style “tended to inhibit initiative” during the Civil War, Dr. Hess notes, and his subordinates complained with disbelief that “he never could understand a map.”

5. FORT GORDON, Georgia

Though he had no prior military training, John Brown Gordon was elected captain of his Georgia company, and went on to fight with distinction – and in the wake of some major injuries, including five gunshot wounds suffered during the Battle of Antietam. After the war, he served as a U.S. senator, as governor of Georgia, and, rumor has it, as a leader in the Ku Klux Klan, which he denied.

6. FORT BENNING, Georgia

A vocal activist for secession, Gen. Henry Benning was passionate about safeguarding the wealth of slave owners, and adamantly opposed to freedom for Black people in America. In one infamously racist speech, he worried that if the North won, “the black race will be in a large majority, and then we will have black governors, black legislatures, black juries, black everything,” causing the U.S. to “go back to a wilderness.” His family celebrated his legacy. “This Was a Man,” they had engraved on his tombstone. His wife is reputed to have been an inspiration for Scarlett O’Hara in Margaret Mitchell’s “Gone With the Wind.”

7. FORT RUCKER, Alabama

Edmund Rucker enlisted as a private in the Confederate Army, but rose through the ranks through his engineering experience. When Tennessee voted to secede from the Union, more than 100,000 were in favor of the decision, but 47,000 – most in the eastern part of the state – voted to stay. Rucker was assigned to maintain martial law there, punishing those caught burning bridges and forcing into service locals who didn’t want to join the Confederate Army, according to Michael Rucker, who wrote the first published biography of his distant relative last year.

8. CAMP BEAUREGARD, Louisiana

After the secession of his native Louisiana, Pierre Gustave Toutant Beauregard resigned from the U.S. military and became the first brigadier general of the Confederate Army. He was known as a competent commander, taking part in the First Battle of Bull Run and in the defense of Richmond, Virginia. Colleagues complained, however, that his tendency to question orders bordered on insubordination. After the war, he got rich promoting the Louisiana lottery.

9. FORT POLK, Louisiana

Though a West Point graduate, Leonidas Polk had spent most of his life as an Episcopal bishop in Louisiana before the Civil War began. He was appointed by Confederate President Jefferson Davis, his West Point classmate and friend, to be a major general, in the hopes that his knowledge of the Mississippi Valley terrain would be an asset in the war. Polk was killed in 1864 while scouting Union positions.

10. FORT HOOD, Texas

John Bell Hood was known as an initially successful commander who rose rapidly through the ranks – too rapidly, analysts say. Notably, Hood was the Confederate commander in the Battle of Franklin in Tennessee. In what is known as the “Pickett’s Charge of the West,” Hood ordered nearly 20,000 men to charge across 2 miles of open terrain to attack fortified Union soldiers. The assault was beaten back with some 6,000 Southern casualties, including 14 of Hood’s generals, in one of the worst defeats of the Civil War.