The female World War II pilots who got all Congress on their side

Loading...

| Washington

Growing up in west Texas, Nell Bright would watch the old World War I barnstormers fly low over the fields near her home.

One day, her dad asked his young daughter if she wanted to get a closer look at a plane that had just landed. And she was thrilled when the pilot, to earn some much-needed money during the Great Depression days, offered a joyride.

Her dad paid the pilot a couple of dollars to take her up in his “big old open cockpit plane,” Ms. Bright recalls. “He strapped me in and off we went. I never forgot that.”

It was the beginning of a lifelong love of flying that led Bright eventually into service during World War II as part of the legendary Women’s Airforce Service Pilots (WASPs).

Her job involved, among other things, towing targets behind B-25s for the men’s live-fire, anti-aircraft training.

“Sometimes they didn’t hit the target,” she says. “But they never hit my plane.”

And now, Bright’s passionate advocacy alongside fellow WASPs has led to a milestone of recognition, with passage by Congress Tuesday of an act allowing surviving fliers from the service to have their ashes placed at Arlington National Cemetery.

For Bright and others who have championed the idea, it’s the culmination of a decades-long campaign for these female pilots to be recognized alongside other military veterans. But for those it has touched along the way, the effort became something more.

From the techies at Change.org who provided stats to drive the campaign to the congresswoman who was able to return the kindness that the WASP aviators once gave her, Tuesday's unanimous Senate vote was, they all agreed, a fitting testament to the power of a just cause.

• • •

The WASPs did a range of dangerous jobs, from the live-fire training to picking up new aircraft fresh off the floors of the factories that were trying desperately to innovate and win the war for America. Some 38 women died in their service as WASPs during World War II.

Bright watched one of her comrades crash one day. “We were all at the field to support her” with “our fingers crossed” as she took the plane up, only to watch it dive tragically towards the ground below. “It was very traumatic.”

When these women died, she recalls the government being officious, which is to say, not particularly kind. “One of the girls’ families got a telegram saying that ‘Your daughter was killed today. Where do you want us to send the body?’ ”

The women would take up collections for the funerals, since the military wouldn’t pay and money was tight for many families. “The government furnished a pine box. Period.” The women’s families weren’t allowed to put an American flag on the casket, either, since they weren’t officially veterans.

The women fought for veterans rights and won them in 1977. But earlier this year, Bright learned that her fellow WASPS could not be buried at Arlington National Cemetery, a development she calls “a slap in the face.”

It was a prohibition that emerged quietly last year, when Secretary of the Army John McHugh overturned a 2002 Army ruling that had de facto allowed inurnment honors at the cemetery for the women.

“While certainly worthy of recognition,” the WASP’s service “does not, in itself, reach the level of active duty service required” for inurnment there, Arlington National Cemetery officials noted in a Jan. 5 post on the cemetery’s website, adding that the eligibility criteria are “more stringent, due to space limitations.”

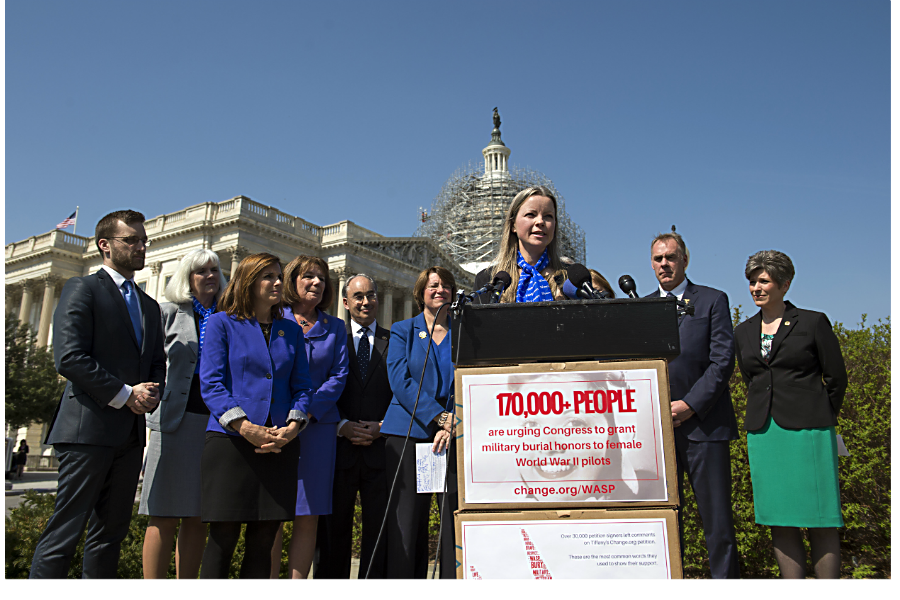

What happened next was a lobbying effort and crowd-sourcing campaign from a galvanized public has prompted first the House, and this week by the Senate, to pass legislation to allow the more than 100 WASPs still alive today to have their ashes placed at Arlington if they so choose.

That the legislation passed both House and Senate unanimously in a time of high partisan discord was heartening, say supporters.

• • •

Among those cheering the action is Erin Miller, whose grandmother, Elaine Harmon, was just the sort of adventurous woman that thrived as a WASP.

Ms. Harmon scraped to get the needed pilot training, paying to use a friend’s plane so she could build up the 75 flight hours that were required of women, but not of men, Ms. Miller recalls.

Strong women accustomed to standing up for themselves, Harmon and Bright later traveled to Washington in 1977 to lobby for legislation recognizing their status as veterans.

They were not warmly welcomed by many lawmakers,“but it was OK, because Barry Goldwater was leading the fight on it,” with the support of the few women who were in Congress at the time, Bright says.

“Of course, some of the good old boys in Congress were still fighting it, and told Barry that he’d never get it out of committee,” she recalls. “Barry had very colorful language. He said, ‘OK, you so-and-so’s, I’m going to attach this bill to every piece of legislation that goes through Congress until you pass it.’ ”

That year, Congress approved veterans benefits for WASPs. As they both grew older, Miller would drive her grandmom to appointments at the Veterans Administration hospital – access to medical care that came through the legislation.

Before Harmon died last April, she left written wishes for her ashes to reside at Arlington.

The family was surprised when last year the Army rejected their request.

Miller’s mom, the executor of the estate, was up in arms. “She’s of that generation of ‘Let’s write a letter!’ ” Miller says. “I said, ‘Mom, that’s great, but I don’t think it’s going to accomplish what you want it to.”

So Miller took to social media, launching a petition on change.org, which quickly took off on Facebook and Twitter.

The question was how to turn a social media success into legislative interest. The staff at Change.org was so struck by the petition’s success – which in short order inspired 170,000 signatories and counting – that they reached out to Miller on Twitter.

“My grandfather is buried at Arlington, so it’s personally resonant to me,” says Benjamin Lowe, numbers guru at Change.org. He learned that Miller was planning to go door-to-door to visit with lawmakers on Capitol Hill, and he also knew that statistics from individual congressional districts would help bolster Miller’s case.

“The power of her story is what’s ultimately going to win the day here,” Mr. Lowe says. But numbers would help get them in the door. So he ran the numbers.

When they went calling on Capitol Hill, “The person at the front desk would ask, ‘Are you from the district, from the state?' ” Erin would respond no, but be able to add “that hundreds or thousands of people from this state, who are constituents, have left comments and support this,” Lowe says. “To be able to carry that information about the district into every office – that was really valuable.”

The key was emphasizing “in the minds of members of Congress the reputational risks of ignoring something that is so clearly an act of passion,” says Max Burns, communications manager at Change.org. “It’s a privilege to serve that purpose.”

• • •

It also helped to have an airwoman ally in Congress. Rep. Martha McSally (R) of Arizona, the first woman to fly in combat for the United States military, learned of the Arlington ban in January through Twitter. She says the “sexism” at the heart of their longtime struggle hit her hard, McSally says – and on a personal level. “These were friends and mentors,” she says.

That the women could be excluded from Arlington at the same time that the Pentagon had finally lifted the ban on women in ground combat struck Representative McSally as particularly egregious.

“We went from hearing about a problem the first week in January to voting on it in March, which is pretty extraordinary,” she says.

McSally recalls how former WASPs helped encourage her military career. “There are certain times when it can be frustrating to break through those barriers – proving we have the capability to be fighter pilots – and the handful of times when I was tired of it or frustrated or discouraged, they would inspire me to fight another day.”

“We just shared a lot of our stories with her – and told her to be sure to get her promotions,” says Bright. “But we didn’t have to worry too much about Martha. She went from captain clear up to full-bird colonel.”

Now that the legislation sponsored by McSally in the House has passed the Senate, only some congressional formalities remain before it heads for an expected signature by President Obama.

In the meantime, Harmon’s remains sit on a closet shelf in Miller’s house.

For her part, Nell Bright, who married, had children, and launched a post-military career as one of the first woman stockbrokers in Phoenix, doesn’t even want to be buried at Arlington.

After moving to Salt Lake City to be closer to her daughter, Bright wants to be buried at Fort Douglas, a “gorgeous” old military cemetery. “I’ve pretty much gotten permission, but they can’t actually reserve a spot,” she says.

For those who do want Arlington honors, “I mean, there are only 100 of us left – and there are probably not even half of whoever’s left who wants to be buried there.” To not allow it would be “ridiculous,” she says. “We’re veterans – and we should have that privilege.”