Fallujah anniversary: Tracking down the US Marine 'Death Dealers'

Loading...

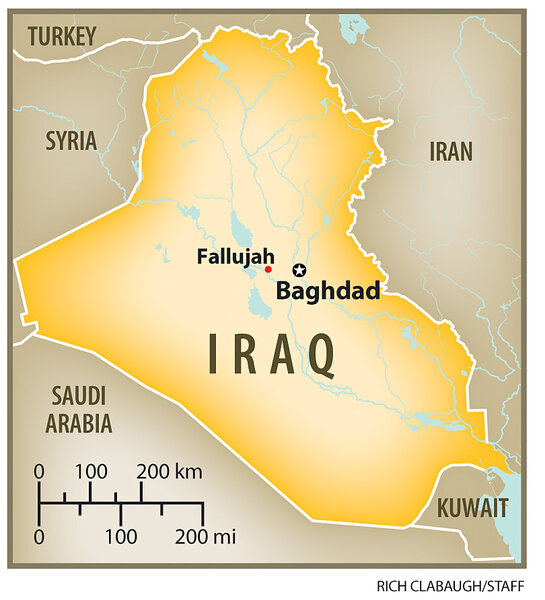

Fallujah. The word alone conjures up grim images of Iraq’s most intense urban combat, of insurgent snipers and dark narrow streets riddled with explosives, of militants lying in wait for days to kill Americans with assault rifles and grenades.

Fallujah still haunts those who fought – jumping roof to roof and blasting through windows and doors night and day for weeks – to hunt down every insurgent in a city largely emptied of its 300,000 civilians. Fallujah even inspires awe among soldiers and marines who were not there in November 2004 for the battle that defined a new generation of American war fighters.

US Marines – 6,500 of them – led the charge. They found their enemy and killed them, or forced them into acts of suicide. In apocalyptic scenes during firefights, insurgents leaped with live grenades out of the shadows inside burning houses, or blew off their own heads as they ran out of bullets.

Operation Phantom Fury was proof of Washington’s calculation that Fallujah had to be destroyed to be saved. And at the tip of the spear were the 10 or so marine scouts of Raider Platoon, the self-styled “Death Dealers” of Charlie Company, 1st Light Armored Reconnaissance (LAR) battalion.

The company lost 20 percent, dead and wounded, of its own members in Fallujah – while expending more than 20,000 machine gun and rifle rounds, 300 grenades, 50 rockets, and 700 shotgun shells. I was embedded with Raider Platoon in Fallujah for the Monitor and took shrapnel in my arm.

Military history books will record how Fallujah was demonstrably cleared of more than 4,000 Sunni insurgents in 2004. And they will mention that today Islamic State fighters control the city – a reversal for Fallujah that shocks and angers the many who had fought so hard and bled so much.

But there is another, powerful history of Fallujah – about the toll of the after-war, and its effect on the Americans who fought in that battle.

Ten years later, these marines still grapple with the memory of fallen comrades – and the guilt of surviving when others didn’t. Often soaked with alcohol, they have struggled with multiple forms of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), suicidal feelings, blinding rage, fits of violence, deflated expectations, and the challenges of daily life. They often bottomed out before they could rebound. Some have been saved by wives and girlfriends, by their own faith, and by their fellow fighters.

“There was a sense of importance, and clarity of purpose, that doesn’t seem to exist in civilian society,” says Capt. Cameron Albin, the former company executive officer, who has suffered heavily from PTSD since Fallujah and is now turning his life around in Austin, Texas.

“Reinventing oneself is not easy.... At one point, I was competent, capable, respected, and felt as though I could accomplish anything. Then it all evaporated, and I felt utterly useless, worthless. Regaining even a fraction of my previous confidence is a daily challenge.”

Similarly, the damaged lives of Charlie Company are almost impossible to quantify. Yet the problem is not going away, and Fallujah and the wider Iraq and Afghanistan wars have created a new generation of veterans with Vietnam-style issues that are costly and will be around for half a century, says Lt. Col. Gil Juarez, the company commander in Fallujah, who is still on active duty in the Washington, D.C., area.

A decade ago after the heaviest fighting in Fallujah, then-Captain Juarez told me in a reflective moment that “everyone has their limits, and their triggers.” He worried that when marines no longer had their mission to focus on, back “home is where things can happen.”

Indeed, surveying the results so far, Juarez says: “We still don’t know the price of these things.... America doesn’t have a deep enough discussion [about] what’s going to come after guys come home.”

Many of these marines wear bracelets to remember their dead. Ten years later, no one who fought in the caldron of Fallujah remains unchanged by its horrors. From the scorpion-pricked deserts of Texas to the deer-filled woods of northern Pennsylvania, this is the story of how the “Death Dealers” have coped with the pinnacle experience of that battle.

The Texans

With a practiced arrogance, Matt McClellan steps up onto stones in his backyard, points his weapon over the high fence, and curls his lip as he pulls the feather trigger to unleash dozens of rounds.

I had seen Mr. McClellan in a similar pose countless times a decade ago. As a young lance corporal with a pistol holster on his shoulder, he blasted his machine gun at Sunni insurgents in Fallujah, leaving a trail of smoking brass casings as the “Death Dealers” cleared blocks of houses.

But today, McClellan’s tool of destruction is a $1,500 state-of-the-art paintball gun, and his target is a dumpster behind his suburban Midland, Texas, house, now splattered yellow. He is obsessed with paintball, and his Fallujah-honed prowess shows in competition. He’s considered going pro, but, at 31, he tells me he is too old and “behind the power curve” – never mind that, ever since Fallujah, his back is so messed up he can only sleep if there is a pillow under his stomach.

The lanky and unshaven McClellan appears to be doing OK. He has a good job as a laboratory technician in a Texas oil town booming so much, he says, that when you throw a stone you hit three millionaires and a veteran. His wife, Melissa, works as a bartender and gave birth to their first baby on Oct. 21 to rapturous welcome.

Weeks earlier, on a warm September afternoon, smoke rises from the barbecue, where the former marine repeatedly bastes two long racks of ribs with his own sticky brown sugar and chili-kick sauce. Beer flows and the dogs bark noisily and often, disrupting conversation.

The tattooed McClellan is still a serial rule-breaker, as independent as he felt he was invincible in Fallujah. As a juvenile, he tallied 26 counts of grand theft auto, which were dropped from his record when he turned 18 – a fact that Melissa, whom he married in late 2013, will first learn when she reads this. In his youth he had seven ear piercings on one side, six on the other, a tongue stud, and a lip ring.

I never thought that “trigger-happy Mick” – as he called himself – would survive a decade after Fallujah. He jokingly says he thought the same about me.

“I always pictured World War II-style – like confetti and flags waving, and people so glad to see me, saying, ‘I hope you come and work for us,’ ” says the New Jersey native of his 2006 homecoming.

But reality hit like an IED, and nobody hired him.

“I started getting into a bar routine. I’d go to this bar on Monday, and that bar on Tuesday. I became a drunk.... All I cared about was ‘where’s the next beer at, where’s the next party,’ ” recalls McClellan. He was living on his veteran’s pay while Melissa worked. He says, “I didn’t care about her,” only about “staying home, video games, watching TV.”

Fellow Charlie Company “war pig” – named after the distinctive squat shape of the unit’s armored vehicles – Mike Ball invited the couple to Texas in July 2009. They felt at home; all the hiring signs convinced them to stay. And nearby was another 1st LAR vet, Dustin Barker, who was having his own post-Fallujah issues. He had been close to McClellan in the Marines; their best friend was Lance Cpl. Kyle Burns, a cowboy from Wyoming who was killed in an ambush in the first days of Phantom Fury.

“They’ve all migrated to each other,” says Melissa, praising the ad hoc mutual support network.

Mr. Ball – today a Midland policeman who actually patrols McClellan’s neighborhood – for years blamed himself for the death of Burns, feeling guilty because his platoon had been sent to Najaf instead of Fallujah. In Najaf, Ball saved a marine’s life and was decorated for it. But guilt over Burns, and drinking after the Iraq experience, prompted him to disavow those awards, at one point throwing them out of his car window in a rage.

Ball’s darkness for a time was so complete, it rivaled that of addicts. “Even meth heads and crackheads are looking for another hit. But [Ball] had no light at the end of the tunnel. It was all negative,” recalls McClellan. “He’s better. We’ll talk about Kyle. To us, it’s better than going to a shrink.”

And in Texas, amid his fellow marines, McClellan himself snapped out of it.

“He’s come a million miles from when I first met him,” says Melissa, who can solve a Rubik’s Cube in under a minute. “The first six months, I totally didn’t think we were going to make it.... That whole Jersey bar scene [meant] he didn’t have to live with whatever was going on in his head.”

Today, besides paintball, McClellan is still into eardrum-splitting heavy metal. His man cave is cluttered with beer bottles, and the house is full of high-end paintballing equipment – and cribs, strollers, and baby clothes for the new arrival. “Since I’ve been down here,” he says, “this is the best I’ve ever done in my life.”

About 45 minutes from McClellan’s home, past scrubland pocked by always-moving jack pumps bringing oil up, Mr. Barker manages 300 head of cattle on a “modest” ranch – by Texas standards – of 33,000 acres.

Barker, who wears a black cowboy hat with a band sweated through, crusty with dirt and holding a long turkey feather and several toothpicks, shares a rugged ranch life with his wife, Meredith, and their three children. The family killed 39 scorpions in their carport in just three days in September, and two days before I got there, Barker smacked a four-foot rattler with a shovel. Trophy deer heads with large antlers define the TV room – one of them shot by Meredith, a smiling pillar now for all the family.

“[Meredith] saved my life, there’s no doubt about it,” says Barker.

“When I get blackout drunk – and I got blackout drunk a lot – I just get mean,” says Barker, matter-of-factly. He was raised in a Baptist family that did not drink, and before joining the Marine Corps, neither did he. He says 90 percent of his problems relate to Fallujah.

“I was hitchhiking, and passed out in the middle of the road, getting in fights,” recalls Barker of his rough return to civilian life in mid-2006. “She put up with so much of my [expletive] and got me to where I am now. In my mind, I would have been killed in a drunk-driving accident, or stabbed or shot, because I didn’t care who you were, I was going to fight you.”

Back then, says Meredith, who has known Barker since junior high school, her husband had one default mode: “Every emotion: If he was scared, it was rage. If he was sad, it was rage. If he was embarrassed, it was rage.”

Even after their beautiful wedding, recalls Meredith, they were drinking and “something snapped and he lost it.” He called her names, chased her back to the hotel room, and they got in a fight. “Finally I just went out onto the balcony and hid in a corner until he passed out. I mean, that was our honeymoon.”

Barker was good at apologizing, but angry with himself, too.

“There were so many times I wanted to just smoke my [expletive] head,” he says.

On New Year’s Day in 2010, he nearly went over the edge during an argument with Meredith that escalated. Finally, Barker put a gun in his mouth. “Honestly, at that point, I was just thinking ‘pull the trigger and get it over with, and get this [expletive] done.’ I was ready to smoke myself.”

Meredith called 911, police arrived, and Barker was held for 30 hours. After that, he saw a counselor. They started talking. “He always fell back on Fallujah.... I told him: You can’t keep going back there because you are screwing everything up.”

Those days are over, says the man whose Marine Corps plaque in a bookcase with family photos is engraved to Dustin “Hillbilly” Barker, commended for “unbounded enthusiasm” and “superb professionalism.” One photo shows baby son Kyle – named after Burns – asleep in the helmet Dad wore in Fallujah.

“There’s too much to live for now” to think of suicide anymore, says Barker, listing his wife, his kids, his house, and his ranch.

McClellan, too, has good reasons to continue his rebound. Not to be outdone by Barker’s Kyle, McClellan has named his new son Kyle Blake, after Burns and Lance Cpl. Blake Magaoay, who was also killed in Fallujah.

“I have plans for Kyle,” McClellan says of the newborn, as Melissa smiles. “When he’s 10, I’ll get him his first gun, and we’ll play paintball.”

The Intellect

For Capt. Cameron Albin, solace from years of deepening PTSD and alcoholism finally came in the form of a sailboat and a puppy – and clearing his mind of everyday sensory overload.

Deployed to Iraq for the 2003 invasion – when a 500-pound bomb was fired too close to his vehicle by a US jet fighter – he was back for Fallujah and hard-wired for the fight. Short, with penetrating eyes and a tongue that moves almost as quickly as he thinks – which is fast – Albin has been in and out of military rehab programs for years.

Medically discharged in 2011, the Texas native today has put his boat up for sale, still enjoys his dog, and is studying in Austin for a master’s degree in military history and to find “an aim and purpose.” He wants a PhD and hopes to teach. He swims, runs, and works out in the gym six days a week, and hasn’t had a drink in two years.

That’s the good news.

The bad news is that PTSD for years wrecked his life, including brief jail time and two tickets for drunken driving, and he knows exactly why: “When you first get off the plane [from Iraq], there’s that feeling, ‘Yea! I didn’t get shot in the head, and I’m back in the States. Party like a rock star!’

“And it’s not until you’ve been home a few days and try to do something normal, like go to a grocery store, and you have some idiot hogging up the whole aisle ... and you want to reach out and strangle the ever-loving [expletive] out of them.

“Or you are waiting for some hajji to leap out of the frozen-food aisle and blow himself up,” says Albin. To him, PTSD is more “behavior modification run amok” than anxiety disorder, thanks to Marine training and battlefield realities.

“Your brain has been altered to function in a permanently heightened state, with certain preprogrammed responses that are violent and aggressive,” says Albin. “Your brain is saying, ‘Get ready,’ and your body is responding appropriately, but there’s nothing to get ready for. There are no ninjas in Wal-Mart....”

As if searching for a way to synthesize his thoughts, he looks around at the prosaic scene in the Austin restaurant where I first met him to catch up – where the busboys work or don’t, and the clientele ranges from misbehaving kids to older couples – and he reaches for an example. “Have you ever had an eye exam, where they dilate your pupils and they’re taking in too much light so you have to wear sunglasses for the rest of the day?

“Imagine that happening to all your senses. That is the hypervigilance component. Your senses have been permanently dilated to take in all this information, and when you’re in some place like this, your ‘fight or flight’ response is being triggered.... It’s a really [messed] up way to live, and it’s exhausting.”

When he was drinking he often had flashbacks, including one of when he nearly shot an insubordinate marine in 2003. One flashback in 2012 was triggered, he thinks, by odd overhead streetlighting that took him back to Baghdad: “Some gangbanger wannabe punk sitting in his car decided to talk [disrespectfully] to me as I was wandering around, walking out of a bar. I guess he just thought I was some skinny white dude, and instead of talking to Cameron the drunken boat hippie, he was talking to Lieutenant Albin, circa 2003, and that [guy] was crazy!

“So apparently I reached through the window, pulled out my pocketknife and held it up to his eyeball. I said: ‘Get the [expletive] out of the car.’ I thought he was being an ornery hajji,” says Albin. “The cops got called.... I remember snapping out of it, finding myself standing in the parking lot.... When the cops arrived, I remember putting my hands in the air and asking them, ‘What happened? What’s going on? What did I do?’ Then they tackled me.

He was jailed for two weeks.

In those days, grain alcohol was his “primary form of nutrition.” Several abuse programs failed, he says, because they did not address the underlying cause: living with the ghosts of Fallujah and Iraq.

“Fallujah left its mark on everybody; it just manifested itself in different ways on different people,” says Albin. In late 2012, for example, he had a call from Greg Eddleston, the company maintenance chief in Fallujah. Mr. Eddleston was struggling with alcohol and the Department of Veterans Affairs had told him he had PTSD. Albin joked that they all had it, that he was making progress and would help Eddleston.

“I thought he was doing all right,” recalls Albin.

But a couple of days later, he got a text message from Eddleston that ended with his Fallujah radio call sign: “It’s morning here now, but it is night for me. I am in a hell that very few know and I am worn thin. I am tired of fighting and I brought more pain I can not go through again. I bid you good bye. Black 9 out.”

That day, Eddleston committed suicide.

Four months later, Albin lost another friend, a former marine who was going to sail with him one morning across Chesapeake Bay, but never showed up. “I never heard from Dave,” says Albin.

He later found out from a police investigator that Dave, apparently drunk, had killed another buddy, and then himself.

For Albin, sailing taught a better path. He may one day start a nonprofit that uses sailing to treat PTSD.

“You get people away from the sensory clutter of everyday life. You put them on sailboats, put them in the woods, put them on a mountaintop; you have them make sombreros in the desert in New Mexico ... so that they can find some clarity of thought,” says Albin. Then they can identify problem behaviors and “come up with tangible solutions.”

“If there was anything I lost ... that I wish I could have back – in addition to those 23 IQ points that were blasted out of my head – it would be the sense of focus, the intensity, and the ability to follow through,” adds Albin.

Are you easily distracted? I ask the guy known for intelligent focus and a way with words back in Iraq.

“Oh yeah, it’s like: Squirrel!”

The Wise Man

The wake-up call comes at 4:52 a.m., when Alison starts to cry. The voice of his daughter, a sprite of an 18-month-old with wispy blond hair, soon stirs former marine Tim Milholin. He comes downstairs to the kitchen and starts making coffee – just as making coffee was the corporal’s first order of business for us in Fallujah every day, a decade ago, on a small camp stove on the floor in whatever abandoned house or wrecked building we had laid our sleeping bags in.

By 5:45 a.m., his wife, Brianne, is downstairs, too, making school lunches for Jadyn and Savanna, who arrive for breakfast and add to chalk drawings on a large blackboard of characters from the movie “Frozen.”

It may not be exactly the image of blessed contentment that Mr. Milholin expected. Ten years ago in Fallujah he told me he was “looking forward to the simple life,” including a house “with a porch and a rocking chair, and cleaning my shotgun all day.”

But up here north of Trout Run, in heavily wooded, gun-toting north-central Pennsylvania where permanent signs say “Hunt Safely,” the Fallujah veteran has indeed begun to live the dream, with a picture-perfect, red-shuttered, two-story house at the end of a long driveway.

So far there are only two kid-size rocking chairs on the porch, because Milholin has been too busy for one. He carried a photograph of his bride, Brianne, in his helmet in Fallujah, and Jadyn was born before he left the Marines in 2006. Since then, the family has grown, and moved, and Milholin has earned degrees in engineering and surveying.

“I don’t think he really had time to fall apart. Maybe he had something to come home and look forward to,” says Bri, about how Milholin has coped with the Fallujah after-war.

“This is definitely our sanctuary. We are definitely blessed,” says Milholin, who credits family and faith for his being able to keep it all together.

In Fallujah, he was one of the three religious “Wise Men” in the company, and still has the blue zip-up Bible he kept next to his heart in Fallujah, under his armored vest, the sweat of multiple operations still sticking onionskin pages together.

Nearly a decade ago, he told me how he prayed every day, and believed during battle “that God puts his angels out before us, to protect us.”

That guidance continues. “I didn’t know what I wanted to do, but when I stopped worrying, and spent a lot of time in devotion,” Milholin says, “God put [engineering] in my heart. Everything fell into place.”

He adds: “Having that faith to rely on [is] where my strength comes from, from my faith in Jesus Christ and the close-knit family.”

But Fallujah had an impact. I remember Milholin as part of the first entry teams into houses during clearing operations, day after day, who raced through their own grenade smoke, sweating hard with guns up, room after room.

He has the original “Death Dealers” banner – a home-made skull and crossbones superimposed over a cross – that flew for a time over our scout vehicle. That flag may one day be framed, and its design inked onto his back.

“[Bri] says I am a lot less emotional now. She always makes comments that she has never seen me cry,” says Milholin. “I definitely think it hardens a person, going through those experiences, and makes you less quick to react with emotions.... It’s a natural way to protect yourself.”

These days he enjoys making maple syrup, which requires boiling down 40 gallons of sap for every gallon of syrup. This year – tapping his trees and a neighbor’s – he made 4-1/2 gallons of syrup. He has a modest orchard and blueberry bushes and strings of grapevines.

“We’ve got a little chunk of Paradise,” admits Milholin, who works for a survey company and spends most of his free time with his family, his syrup, and his plot of land. “I don’t know why me versus somebody else gets to have a life like this, while so many were either taken from us too early or have to suffer through things.”

Random memories of Fallujah and the 2003 invasion are still set off by watching a movie or hearing a song. When he was in the Dominican Republic on a church-related trip to help build schools, the smell of burning trash and poverty set off his emotions.

And there are other subtle changes that he deals with daily.

“Crowds, cities, I just don’t like them,” says Milholin, who often carries a pistol. “Bri makes fun of me because she says when we go to a restaurant, I have to sit in the ‘gunfighter’s seat’ with a good view and no people behind me.”

Yet the porch and his own rocking chair still beckon.

“I’m getting there.... That’s still the goal!”

The Lone Ranger

It’s near midnight, and police officer Kevin Boyd turns his patrol car left down a narrow lane between old small living units on the northwest fringes of Pittsburgh. There is a sprinkling of rain and the scent of lower income desperation.

“I’ve probably been into every one of these houses,” says Mr. Boyd. He takes many domestic violence calls, and Pittsburgh is known as a heroin town. He may be working in mostly middle-class districts, but just days before my September visit with him he came across two people passed out in a car with needles still stuck in their arms.

For Boyd, wearing a police uniform the past seven years – and recently joining the north Pittsburgh call-up SWAT team – was a natural extension of his time in the war in Fallujah, a combat rush that he says “completely defined” him.

A born warrior and lifelong gun aficionado, with a gung-ho attitude and frontline fearlessness that propelled him up the ranks to gunnery sergeant in record time, Boyd wore his first camouflage at age 3, shot BB guns at Tiger Cub camp, and owned his first gun at 15.

He was an Eagle Scout, and on his police uniform below his SWAT badge he wears ribbons for combat and his Purple Heart – earned in Fallujah when shrapnel struck his chin.

His young-looking face hasn’t aged a day since then. On one police call, a woman called him a “snot-nosed kid.”

Boyd shifted from the active-duty Marines to the reserves in 2005. Then in 2010 he volunteered to spend seven months in Afghanistan for “one last adventure.” Even before the unit left the United States, one fellow reservist committed suicide.

They were meant to quietly guard bases but were instead sent to remote Marjah, in southern Helmand Province, where they were caught up in firefights almost every day. Boyd had the words “The Lone Ranger” on his helmet there, as in Fallujah he had them written on his gloves – along with his blood type and “kill number” (A+, X18), the designation used to identify the dead or wounded over the radio network without using names.

The Taliban welcome on the first patrol was a mine packed with used car parts that took a sizable chunk out of one reservist. Boyd hadn’t been in combat in five years, but Fallujah had permanently sharpened his instincts. He didn’t miss a beat.

“The first things that come out of my mouth are ‘Get cover!’ and ‘Look for secondaries!’ and everyone [else] is standing there, deer in the headlights,” says Boyd of the awestruck younger men. He tied on two tourniquets, and may well have saved the marine’s life.

His girlfriend of a couple years, Rachel, took the Afghanistan tour “horribly,” he says, because she had moved to be with him in Pittsburgh.

Despite the firefights, Boyd had a custom engagement ring made while he was away, and proposed to her the night he got back. “I was still in cammies,” says Boyd, of his camouflage uniform. “She was ecstatic. Very, very happy.”

In all his years on the police force, he has pepper-sprayed one person and used a stun gun on two – and has never used his gun. “We have a quieter area. So I feel like I still have very good restraint and control. Do I get mad and yell and go ‘gunnery sergeant’ sometimes? Yeah, sometimes you need to,” says Boyd. But other times, “I’m the biggest sweetheart you’ll ever meet.”

He prefers night shifts because he’s a “drunks and drugs” kind of cop, while “during the day, people’s problems are too small. I just don’t relate to some of them,” he says. “You get the barking dog. You get the raccoon.”

Boyd says his drive, motivation, and need to keep busy have meant little time for negative fallout from Fallujah. Instead, the combat and scenes of streets lined with dead insurgents and body parts has prepared him to handle bad car accidents and suicides.

“I am thankful for what I have had the privilege to experience, as good and as bad as it was,” says Boyd. “It was a privilege. I can’t believe I was able to go through that stuff and still be OK with things, and working.”

There are a handful of toy soldiers on his desk at the police station; his desk drawer is packed with ammo and gun-cleaning gear.

There is a gun safe for his specialized weaponry – on the job, Boyd carries his own Nighthawk Enforcer 1911 pistol. “I always say my bling is my weapons,” he says, with a kid-in-the-candy-shop smile. “So instead of having a $3,000 watch, I have a $3,000 pistol, because it’s the custom stuff.”

At home now he has more than 30 weapons, some requiring federal permits, in a downstairs hideaway that smells of gun oil. On the wall is a large photograph of mine: Boyd’s gloved hands in Fallujah holding a couple rifle clips. The gloves themselves are resting on the side of the stairwell, among mementos.

“Some guys do Fantasy Football, or collect stamps. Some guys golf,” says Boyd. “I don’t golf. I collect guns and I go to the shooting range.”

Almost every day on the street, he sees the other, darker side of less-fortunate veterans – “DUIs, stuff like that,” he says. “It’s slow for them to get back into the swing of life.... Have I shed tears for Kyle and everybody? Of course. They’re family members; they’re friends,” says Boyd. That is raw emotion that needs processing and separation from the “real bad stuff,” but it doesn’t need to be overanalyzed, he says.

“It was what it was. It was war. You can’t sugarcoat it; you can’t say it wasn’t real. What happened to Kyle could have happened to me at a moment’s notice,” says Boyd. “We are lucky and thankful and blessed we are here.”

The Financier

The aspiring certified public accountant wakes at 5 a.m. in Falls Church, Va., studies hard for his exam, and leans into his work with a neck injured four times in Fallujah and other US Marine ops.

The immaculate apartment is tastefully done in all white, the books and computer needed to study for the final part of his CPA exam spread across the table – the only glimpse of chaos in the room.

Christopher DeBlanc keeps a Glock 19 pistol with a 15-round magazine that is “the gun I trained on, the gun I carry,” he says. “You never know when a situation’s going to pop up. And who is the first responder to any situation? It’s the person who’s there.”

Tall, with hair kept combat short, Mr. DeBlanc today projects an air of confidence and puts thought into his words. But his post-Fallujah life has been one of dramatic transformations.

Broke when he left the Marines in 2005, DeBlanc now is “very excited” about finance and accounting, and contributes all he can to his 401(k) retirement funds. His usual fiscal discipline eventually gave way to his “one reckless purchase in life” – a black BMW 335i xDrive parked in the basement garage below.

DeBlanc’s first marriage fell apart after he returned from Fallujah, because his wife “didn’t understand” the impact of his experience. But now there are smiles again: DeBlanc remarried in September to a fellow finance wizard, a US-educated Afghan woman and former college classmate named Sofia who became his “best friend” as he struggled for years with bouts of rage.

DeBlanc, whose nickname was “Debo” in the Marine Corps, went to community college and then university, has a degree in business administration, and works as an accountant. But returning from Fallujah was brutal, says the marine who, as a team leader on the battlefield, was determined to succeed.

“Your whole world is survival. It’s very simple: What do I have to do to survive? There’s nothing else to think about,” says DeBlanc.

“The next thing, when you get back, it’s cellphone bills and rent and groceries and cars broken. The complexity of life grows exponentially. And that initial shock I did not handle very well,” recalls DeBlanc.

“Ultimately, it all boils down to control. And when you are in Iraq and you’ve got a gun, you control the world. You exert that control with violence,” he says. “So when you come back to the States ... where you have no control over the situations around you, I think you revert back to what worked before: violence. Of course, in society you can’t exert violence. So at that point, I think helplessness sets in ... and rage. Blinding rage.”

Did you experience that, I ask? “Oh yeah, all the time, every day. And it would be the littlest thing” – things like the toilet paper being hung upside down.

“Everything would go red, and I would explode,” says DeBlanc. “Yelling, poles through doors, throwing stuff. When I was out and about, in front of people, I think I was fine; I put on a good show. But inside, at home, my wife saw everything. She took the brunt of it, unfortunately. Thank God I didn’t beat her or anything like that.”

The couple had dated just six months before DeBlanc deployed to Iraq for the 2003 invasion. When he came back, they got married. Even back then, he felt his first bursts of rage. But then he was back in Iraq – this time, Fallujah.

DeBlanc was all business and God, one of the three religious “Wise Men.” Gone were his youthful flirtations worshiping the guitar. He told me at the time, “[I] didn’t like how my life was going, so I gave it to the military.” He wanted to emulate his grandfather, a World War II veteran buried with honors.

But in Fallujah, as other marines called home, or were quoted in the Monitor’s pages about missing their loved ones, DeBlanc only spoke about the mission. He made his one brief call an anodyne chat about finances. “She hated me for that,” recalls DeBlanc. When he got home he threw himself into life, working 50 hours a week at a lumber yard, going to school full time, and being married. It wasn’t sustainable.

When he was in public he was skittish and always looking over his shoulder. One time driving on the highway, a tractor trailer next to him blew a tire. “I blacked out. It was like an IED going off. All I remember was, I was in the desert. I heard this boom, and I was in the desert in a Humvee. Then I snapped out of it and I was miles down the road.”

In 2008 he was “politely asked to leave the house,” says DeBlanc. “That was when I realized I had a problem, like I’m a lunatic, I can’t control myself.” His wife asked for a divorce, prompting unbearable pain.

“I could barely function it was so bad,” says DeBlanc. “Everything that I had built my life around and was working hard for, at work and school, for a successful family, it all fell apart. Everything that was holding my world up was gone, so I crashed.”

Remarkably, the divorce ended DeBlanc’s rage. “It was gone. It was a cleansing. I could sleep at night. I didn’t have nightmares – and I had had nightmares for three years, waking up looking for your rifle, or getting overrun, you’re clubbing Iraqis with your rifle, just crazy stuff. And that was the last of them.”

But rebuilding took time.

Sofia could sense his hurt, recalling that “his smiles were not real smiles.” She says she felt he needed “someone to give hope [that] it is not the end of everything, and the sun will rise again tomorrow morning.”

She also had her own war-related experience. Her family had moved to Pakistan when she was young to escape war in Afghanistan, where she had witnessed explosions and many casualties. She was chosen for a study program in the US and today works as a CPA, playfully niggling her husband about his upcoming test.

Sofia calls her husband a “real-life hero” for overcoming his challenges. DeBlanc took a job with DynCorp, and from late 2011 to mid-2013 worked in northern Iraq to provide security for US diplomats. He Skyped Sofia every night.

Surprisingly, going back to Iraq did not trigger bad vibes, he says. “It felt like coming home. I had a gun, and I had power. And life became simple again.”

How did the fight in Fallujah affect his religious faith?

“At that moment in Fallujah, I had come to terms with the fact that I’m about to meet my creator, that I’m going to die. So it’s easy to be close to God,” says DeBlanc. “When you are back here, dealing with life, I guess I find myself drifting away.”

A decade ago, on Day 12 of the Fallujah offensive, several marines got into an argument about religion while cleaning their weapons. DeBlanc said, “God has a perfect plan.”

He still reads his Bible, but less now. And he hasn’t been to church since going overseas in 2011.

“He’s still working that plan out,” says DeBlanc. “I am not as close to God now as I was then. If I had [been killed] at that time in Fallujah, I was completely ready. Now, I may not feel as ready.”

The Commander

Day 14 in Fallujah, and gunfire erupts nearby. We are clearing houses, and the radio carried on one marine’s back bursts to life: Another platoon ha been ambushed, and there are casualties.

My sharpest memory of the company commander, Capt. Gil Juarez, is defined by what happened next. When I race back, he is directing the battle fromthe turret of his “war pig” wearing a helmet, headset, and his look of understated master-of-the-universe determination.

“The fight is over there!” he shouts to me, pointing down a long block and to the left. It’s a typical decrepit Fallujah street, strewn with debris and trash, and lined with low-hanging cables that give it a tunnel effect. Insurgent snipers have been shooting it up.

His belt-fed M240 machine gun is already pointed down the length of the street. Juarez puts his gloved hands up to the weapon.

“I will cover for you, but you must run!” he roars. And as the shooting starts, I run the length of that urban gantlet fast, holding two cameras close, chest heaving under the weight of a bulletproof vest with its two heavy armor plates. Around the corner were wounded marines, and the start of a fierce firefight with four insurgents that would go long into the night and yield more marine casualties – one dead and eight wounded, in all – and a pea-sized piece of shrapnel burned into my arm.

Juarez is the marine’s marine, a commander who at once remains aloof from his men – demanding, receiving, and earning unquestioned loyalty – while also serving as one of the brethren, unafraid of dirt-level war fighting, of the decisions that put them in harm’s way, and unafraid to describe the bond shared by marines as “love.”

So I understand now, a decade later, when one marine says this about Juarez: “I would follow that man to the gates of hell, again.” I heard that sentiment repeatedly, about a man who is still in the US Marines, who has since commanded the entire 1st LAR battalion, and who is today getting a master’s degree at the Marine Corps War College in Quantico, Va.

But the demands of leadership in Fallujah have a particular cost, when your decisions inevitably raise the death toll.

“You always know, in the back of your mind, you’re going to do all you can to take care of your guys. But at the end of the day, the enemy gets a vote, and things don’t always go according to plan,” says now-Lt. Col. Juarez in his apartment across the Potomac from Washington, D.C. “There are surprises, it’s dangerous, and people get killed. And your decisions are the things that drive those people into those situations.”

He is philosophical about the price paid in Fallujah and says he would “do anything” to get back any one of the six marines who died in that deployment under his command. But, he adds: “It’s called war, and it’s called combat for a reason.... I’ve tried never to lose sight of that. Those marines died doing what they volunteered to do. You’ve got to respect that ... because there are always the what ifs, a million what ifs.”

In Fallujah, Juarez was an uncompromising taskmaster, but with a common touch. During one operation, when a slightly wounded marine was escorted back to base, taking him and the one available medic away from the front line, Juarez invoked the memory of a Vietnam-era Medal of Honor winner.

“You’re [expletive] marines. You suck it the [expletive] up,” Juarez admonished. “Do not pull combat power out of the [expletive] fight unless you have to. Like [expletive] John Bobo in Vietnam. [Expletive] leg blown off, he [expletive] sticks his stump in the ground and he mans a machine gun so his platoon can withdraw. That has to be your mind-set. We clear on that?”

Likewise, on Thanksgiving Day, 2-1/2 weeks into the Fallujah offensive, a turkey feast was sent to the frontline house we were occupying. There had not been water or time enough to bathe and until then we’d only had meals ready to eat. Juarez took several steps up a staircase to say grace for all the company. “Some of you might not pray. Some of you might,” he said, using the voice of a reluctant preacher. Many pulled thick hats off buzz cuts and clasped their hands in front of them. Juarez said:

Lord, thank you for keeping us alive....

Keep us strong. Keep us together.

Make us shoot faster than the enemy.

Make us move faster than the enemy.

When he tries to kill us, let us kill him first.

Take care of our families.

And definitely take care of our friends that are gathered here today.

For truly there is no better group of men,

than the men you see here before you.

The risks of the aftermath of Fallujah for Juarez were evident when the unit stopped off in Thailand on the way home. The stories of heavy drinking and debauched celebrations are legend. When it was over, Juarez wanted to set an example. He announced that he was quitting drinking for good – a promise he has kept.

It was a big step for the California native with a tough upbringing, the only one of five siblings to graduate from high school and not get involved with gangs. His older brother is a heroin addict now serving a life sentence in California; he has not seen his sister, addicted to crystal meth, for two decades.

Juarez says he “got lucky” when his family moved to a new neighborhood when he was 14. He had good teachers, ran cross country, and finally channeled being a hell-raiser into the Marine Corps, which he says “saved” his life.

That experience is what shaped his Fallujah after-war. Alcohol is “the medication, it’s the relief, but unfortunately it sucks you in,” he says.

“I told the company: Life now is about not taking a step back. You’ve been through a tremendous event, part of our history now ... but life is hard, and that doesn’t get you much,” Juarez says now. “The world may not know or care to know what happened here. That’s tough, especially for young guys that have been through that.”

When he got home, Juarez says he knew he had “grown impatient and took it out on my family. It took a long time to process that, some anger.”

His wife, Cyndi, stayed with him. “When we were younger, I used to say: ‘We did deployments great, we did reunions very poorly,’ ” she says.

After Fallujah, Juarez was in “project mode,” she recalls. “He took the roof off the house, he tore down the deck – there was nothing wrong with the roof, the roof was fine! He just had to stay busy, kind of engaged.”

Juarez has kept in touch with many of his Fallujah marines and the families of the fallen, ready to guide and support. “It’s hard, because you build a family so tight when you go on a deployment, and when you do go in a fight, you become even closer. Then you come back, and ... the team’s going to get broken up, and you’re going to go different places. You’re not going to have those close buddies with you all the time.

“I just try to get them to be true to themselves, to honor the brothers they lost and the sacrifices they all made,” he says. “[I]t’s all about when you are an old man and you look in the mirror: What are you going to see? What are you going to reflect back on?... That’s more important than anything we did in Fallujah, that they continue to do their best to maintain their honor, to live a good life, to look out for each other, to look out for others. There’s nothing more valuable than that,” he says.

“They love each other. That’s really what’s helped these [marines] get through it all,” adds Juarez. “They’ve not lost that. They love each other to death ... they love each other so much it gets in the way of the rest of their life.”