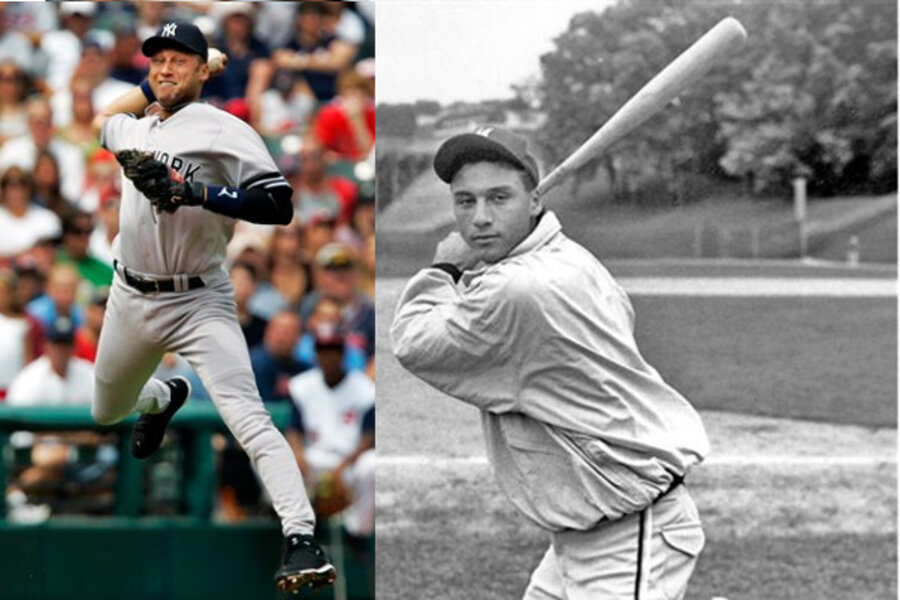

How did 'young colt' Derek Jeter get to Yankee Stadium?

Loading...

| NEW YORK

The 17-year-old kid from Kalamazoo drew all sorts of raves.

He was a "young colt" with a "perfect SS body" and was a "top student" who planned to study medicine at the University of Michigan, too.

"This guy is special," one big league scout even wrote.

But, could anyone back then have projected that Derek Jeter the high schooler would someday become Derek Jeter the future Hall of Famer?

Now 40, Jeter is set to retire after this weekend. A five-time World Series champion and sixth on the career hits list, he spent two decades as the shortstop for the New York Yankees.

Five big league teams bypassed Jeter in baseball's amateur draft in 1992 before New York selected him with the No. 6 pick. A year earlier, Yankees scout Dick Grouch had first spotted Jeter after his junior year.

"It was one of those serendipitous events," Grouch recalled last week. "I was going to cover a tournament on the other side of the state, and I knew they were having this talent identification camp at Mount Morris High School, so I stopped just to get a glance as to what was transpiring."

This time, there was indeed something worth seeing.

"About 5 or 10 minutes in, he was taking groundballs at the time, and then he did things that caught my eye," Grouch said.

With the short high school season, Jeter didn't play many games during the school year, so Grouch watched him with the Kalamazoo Maroons summer league team. And then Jete rinjured an ankle early in his senior season, limiting his playing time.

But Jeter already had caught the attention of scouts for many teams, according to reports that later went to baseball's Hall of Fame.

Cincinnati scout Gene Bennett wrote in April 1992 that Jeter aimed to study medicine at Michigan, adding he "has leadership ability with good makeup" and possessed "skills similar to (Barry) Larkin as high school player."

Larkin, who played college ball at Michigan, became a Hall of Fame shortstop with the Reds.

The California Angels' Jon Niederer noticed Jeter was "somewhat thin-chested and 'pointy shouldered,'" saying he had a "good face — very young looking" and was a "top student from a high class family."

Niederer said Jeter had "all the tools to play the game at a high level." He took note of his "very quick hands and feet — so quick they can get him set up to make a play before the ball arrives and he looks out of synch."

Ed Santa of the Colorado Rockies said Jeter had a "perfect SS body" and projected him to have All-Star potential.

"You get excited just watching him warm up," he wrote in May 1992.

Dave Littlefield, who scouted Jeter for the Montreal Expos and went on to become Pittsburgh's general manager, wrote a report that praised Jeter's body type and bode well for future success.

"Hi butt, longish arms & legs, leanish torso," he said. Among his other remarks was the "young colt" description.

"I think I got most of that right," said Littlefield, who now scouts for the Chicago Cubs. "I wish in retrospect we had picked him."

Jeter says he never really focused on scouts and is pretty sure they first showed up to scout another player on his summer team. Grouch observed Jeter for about a year but tried not to interact with him.

"He always stayed away. He kept his distance," Jeter said.

Grouch had a reason for his behavior.

"I did not want him to know that I was at the ballpark," he said. "I sat in my car. I was in the bushes. I was in the woods. I didn't want him to play for me, because I wanted to see how he handled failure. And every game that he played was the same."

As the draft approached, Yankees' director of scouting Bill Livesey made the trip to Michigan to watch him play. But the entire organization avoided contact. Five other teams were ahead of New York.

"We pretty much zeroed in on him, but none of us wanted to get our hopes up," Livesey said. And when Yankees executives met on the day before the draft, there was one last internal hurdle to overcome — and it was a big one.

"Mr. Steinbrenner was not real high on taking high school kids, simply because they were too long from the big leagues. So we had to convince him," Livesey said, referring to late owner George Steinbrenner, who was suspended from baseball at the time.

"He asked me how long it was going to take for him to be in the big leagues," Livesey said. "It was a little bit of the fib: I told him four years."

The five teams ahead of the Yankees didn't take Jeter. Not Houston, not Cleveland, not Montreal, not Baltimore, not Cincinnati. When the Yankees were up, Jeter was there for the picking.

Jeter signed for a $700,000 bonus (he would make $266 million from the Yankees), reached the major leagues for the first time in 1995 and quickly blossomed.

Grouch says he had a feeling.

"He's going to be able to play in the toughest venue in all of athletics, and that's Yankee Stadium," he said.

"And this guy, he was going to capture this entire city. He was going to capture New York."