Aaron Swartz death fuels computer-crime debate

Loading...

| NEW YORK

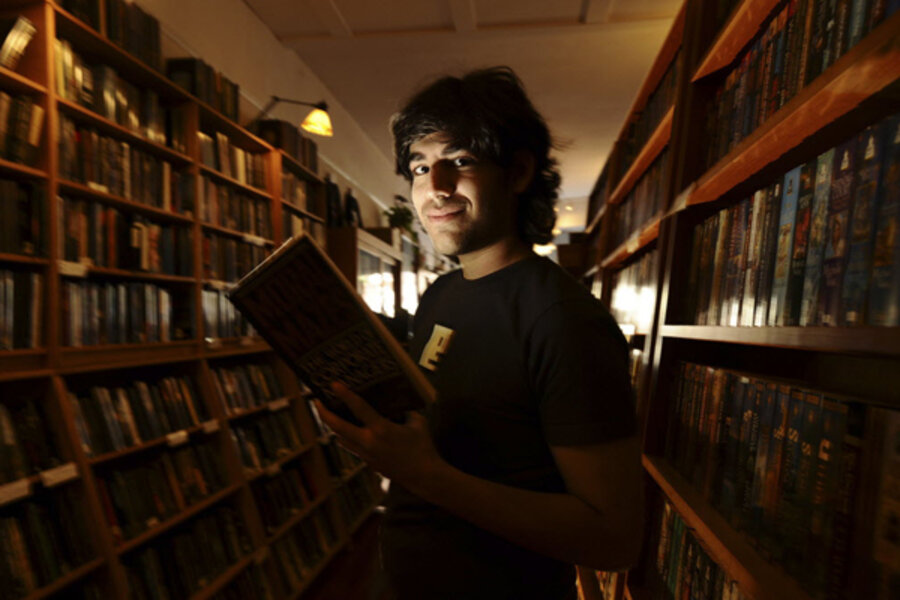

Internet freedom activist Aaron Swartz, who was found dead in his New York apartment Friday, struggled for years against a legal system that he felt had not caught up to the information age. Federal prosecutors had tried unsuccessfully to mount a case against him for publishing reams of court documents that normally cost a fee to download. He helped lead the campaign to defeat a law that would have made it easier to shut down websites accused of violating copyright protections.

In the end, Swartz's family said, that same system helped cause his death by branding as a felon a talented young activist who was more interested in spreading academic information than in the fraud federal prosecutors had charged him with.

The death by suicide of Swartz, 26, was "the product of a criminal justice system rife with intimidation and prosecutorial overreach," his family said in a statement Saturday. Swartz's trial was set to begin in April, with an early hearing scheduled for later this month.

Swartz was only the latest face of a decades-old movement in the computer science world to push more information into the public domain. His case highlights society's uncertain, evolving view of how to treat people who break into computer systems and share data not to enrich themselves, but to make it available to others.

"There's a battle going on right now, a battle to define everything that happens on the Internet in terms of traditional things that the law understands," Swartz said in a 2012 speech about his role in defeating the Internet copyright law known as SOPA. Under the law, he said, "new technology, instead of bringing us greater freedom, would have snuffed out fundamental rights we'd always taken for granted."

Swartz faced years in prison after federal prosecutors alleged that he illegally gained access to millions of academic articles through the academic database JSTOR. He allegedly hid a computer in a computer utility closet at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and downloaded the articles before being caught by campus and local police in 2011.

"The government used the same laws intended to go after digital bank robbers to go after this 26-year-old genius," said Chris Soghoian, a technologist and policy analyst with the American Civil Liberties Union's speech, privacy and technology project.

Existing laws don't recognize the distinction between two types of computer crimes, Soghoian said: Malicious crimes committed for profit, such as the large-scale theft of bank data or corporate secrets; and cases where hackers break into systems to prove their skillfulness or spread information that they think should be available to the public.

Swartz was an early advocate of freer access to data. He helped create Creative Commons, a system used by Wikipedia and others to encourage information sharing by helping people to set limits about how their work can be shared. He also helped create the website Reddit and RSS, the technology behind blogs, podcasts and other web-based subscription services.

That work put Swartz at the forefront of a vocal, influential community in the computer science field that believes advocates like him should be protected from the full force of laws used to prosecute thieves and gangsters, said Kelly Caine, a professor at Clemson University who studies people's attitudes toward technology and privacy.

"He was doing this not to hurt anybody, not for personal gain, but because he believed that information should be free and open, and he felt it would help a lot of people," she said.

Plenty of people and companies hold an opposing view: That data theft is as harmful as theft of physical property and should always carry the same punishment, said Theodore Claypoole, an attorney who has been involved with Internet and data issues for 25 years and often represent big companies

"There are commercial reasons, and military and governmental reasons" why prosecutors feel they need tools to go after hackers, Claypoole said. He said Swartz's case raises the question of, "Where is the line? What is too much protection for moneyed interests and the holders of intellectual property?"

Elliot Peters, Swartz's attorney, told The Associated Press on Sunday that the case "was horribly overblown" because JSTOR itself believed that Swartz had "the right" to download from the site. Swartz was not formally affiliated with MIT, but was a fellow at nearby Harvard University. MIT maintains an open campus and open computer network, Peters said. He said that made Swartz's accessing the network legal.

JSTOR's attorney, Mary Jo White — formerly the top federal prosecutor in Manhattan — had called the lead Boston prosecutor in the case and asked him to drop it, said Peters, also a former federal prosecutor in Manhattan who is now based in California.

Reached at home, the prosecutor, Stephen Heymann, referred all questions to the spokeswoman for the U.S. Attorney's office in Boston, Christina Dilorio-Sterling. She did not immediately respond to an email and phone message seeking comment.

Swartz was charged with two sets of crimes: fraud, for downloading the articles illegally from JSTOR; and hacking into MIT's computer network without authorization, Peters said.

Peters said Swartz "obviously was not committing fraud" because "it was public research that should be freely available;" and that Swartz had the right to download from JSTOR, so he could not have gained unauthorized access.

As of Wednesday, the government took the position that any guilty plea by Swartz must include guilty pleas for all 13 charges and the possibility of jail time, Peters said. Otherwise the government would take the case to trial and seek a sentence of at least seven years.

JSTOR, one alleged victim, agreed with Peters that those terms were excessive, Peters said. JSTOR came over to Swartz's side after "he gave the stuff back to JSTOR, paid them to compensate for any inconveniences and apologized," Peters said.

MIT, the other party that Swartz allegedly wronged, was slower to react. The university eventually took a neutral stance on the prosecution, Peters said. But he said MIT got federal law enforcement authorities involved in the case early and began releasing information to them voluntarily, without being issued a subpoena that would have forced it to do so.

Swartz's father, Bob, is an intellectual property consultant to MIT's computer lab, Peters said. He said the elderSwartz was outraged by the university's handling of the matter, believing that it deviated from MIT's usual procedures.

In a statement emailed to the university community Sunday, MIT President L. Rafael Reif said he had appointed a professor to review the university's involvement in Swartz's case.

"Now is a time for everyone involved to reflect on their actions, and that includes all of us at MIT," Reif said in the letter.

Claypoole, the legal expert, said there will always be people like Swartz who believe in the free flow of information and are willing to "put their thumb in the eye of the powers that be."

"We've been fighting this battle for many years now and we're going to continue to fight it for a long time," he said.

For Swartz's family, the matter was clearer-cut, said Peters, his lawyer.

"Our consistent response was, this case should be resolved in a way that doesn't destroy Aaron's life and takes into account who he really is, and what he was doing."