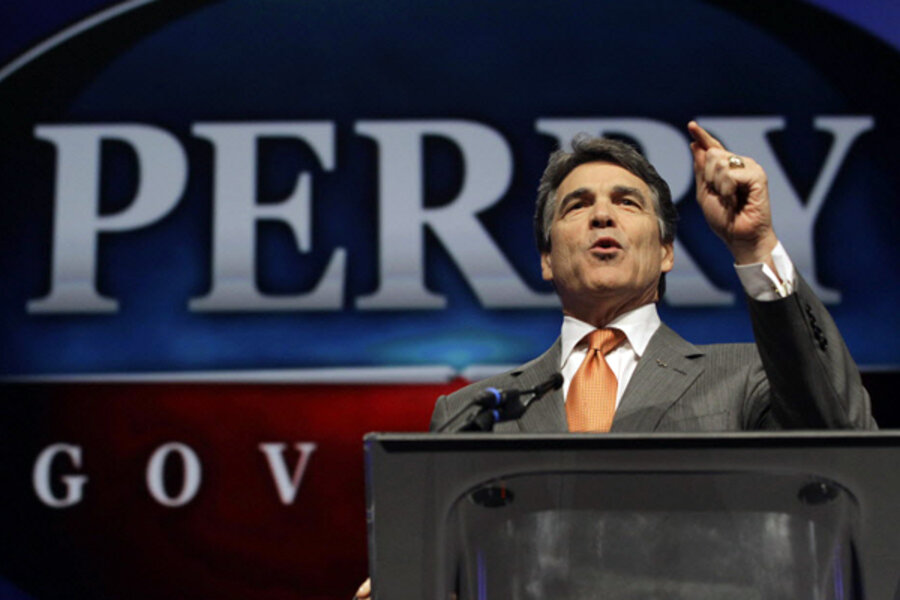

Texas’ Perry rejects Medicaid expansion. What now?

Loading...

| AUSTIN, Texas

Gov. Rick Perry’s declaration Monday that Texas should decline to expand Medicaid and leave creation of a health insurance exchange to the federal government could create burdens for the uninsured, local taxpayers and federal officials seeking to implement the federal health law.

But it’s far from the last word on Medicaid, a continually vexing program for lawmakers.

Soon after Perry fired off a no-thanks-ma’am letter to U.S. Health and Human Services Secretary Kathleen Sebelius and a statement denouncing President Barack Obama’s signature health care law as a “power grab,” health providers said they’d like to see the governor’s plan for whittling into the state’s towering uninsured problem.

Perry didn’t offer one, though he expressed confidence that state officials would do far better if they could use the $18 billion of federal Medicaid funds the state receives each year without conditions.

“Block grant our dollars that we send up there back to the states, and Oklahoma or California or Texas … would make the right decisions about how to deliver health care in their states rather than one size fits all, our way or the highway,” Perry told Midland, Texas, talk-radio host Jason Moore.

The provision that Perry wants the state to reject would add to the state’s Medicaid rolls more than 1.5 million poor, childless adults who are currently ineligible, plus as many as 300,000 pregnant women, children and extremely poor parents who already qualify but aren’t enrolled.

The coverage would begin in 2014. In the first five years, the state’s costs for the expansion would be $5.8 billion, and Texas would receive $76.3 billion in federal matching funds. Despite that prospective gain, Perry said it would be unwise to enlarge “a broken system that is already financially unsustainable.”

The Republican governor also told Sebelius he opposes a state health insurance exchange, which he said would open the door to federal control of Texas’ insurance markets. Some other conservatives have argued Texas should take steps to set up the exchange on its own, in case the federal law survives. If it does, the federal government will establish the exchange.

Federal officials declined to respond directly to Perry, saying that under the law, the exchanges and other benefits will help expand coverage and pledging to work with states to provide flexibility.

Perry’s move was the latest political twist after the Supreme Court upheld most of the 2010 health care overhaul. While most of the legal battles have been over the law’s requirement that individuals obtain insurance, the bulk of the expansion of health insurance coverage is designed to happen at the state level, and GOP governors such as Rick Scott of Florida and Nikki Haley of South Carolina have rebelled.

Many had pinned their hopes on victory in the courts and now hope Republicans can sweep this fall’s elections and repeal the law.

“We’re just not going to be a part of … socializing health care in the state of Texas,” Perry told Fox News.

Parkland Memorial Hospital, which treats many of the North Texas region’s uninsured patients in its emergency room, said Perry’sresistance to the proposed Medicaid expansion won’t stop the flow of indigents seeking care at safety-net hospitals.

“If our state is going to turn away hundreds of millions in federal funds, we are eager to see what our leaders will propose to replace them,” the Parkland Health & Hospital System said in a written statement. The system said that last year it provided $605 million in uncompensated care.

Dan Stultz, an internist who heads the Texas Hospital Association, said Medicaid offers only paltry payments to providers, but having uninsured people flock to emergency rooms for care simply shifts costs to those with insurance. It also places more burdens on the county property owners whose taxes support hospitals such as Parkland.

“With a strained state budget, it’s hard to imagine addressing the uninsured problem in Texas without leveraging federal funds, which will now go to other states that choose to expand their Medicaid program,” Stultz said.

Houston neonatologist Michael Speer, president of the Texas Medical Association, said he’s especially worried about uninsured adults under the poverty line, who were intended to be added to Medicaid and may not qualify for subsidies to buy private plans.

Legislators could attempt to buck Perry on the issue next year, though it’s unlikely enough other Republicans will want to do so.

Either way, Medicaid — one of the largest parts of the state budget — will again be a major issue. Last year, lawmakers helped bridge a $27 billion shortfall by underfunding Medicaid by between $4 billion and $5 billion of state funds. They’ll have to pay the tab in 2013, even though state finances are expected to again be tight.

Texas state Rep. Garnet Coleman, a Houston Democrat who is a leading health policy writer, said Perry “chose the policy that’s best for him politically” but ignored the plight of poor adults, many suffering from diabetes, cancer and mental illness.

“The governor said it’s better to follow his ideology and throw those folks under the bus than to provide health coverage that the state of Texas would pay zero for, at least for the first three years,” Coleman said.

Free-market advocates praised Perry. Merrill Matthews of the Dallas-based Institute for Policy Innovation said that “if enough states push back, maybe they can get the flexibility to try and actually fix the broken Medicaid system.”

Texas could aim to eventually negotiate a better deal, too. For the law to succeed, the administration needs to see the number of uninsured greatly reduced, and Texas has a higher rate of population without coverage than any other state.

States have tended to go along with past expansions of government coverage for the poor and near-poor, even if they first balked, federal officials noted.