The Supreme Court has helped presidential power expand. Trump may test its limits.

Loading...

For the better part of a century, presidents have sought to quickly flex their new powers upon entering office. President Donald Trump has, critics say, taken this practice to an extreme over the past month.

Saying that he is fulfilling a campaign promise to cut waste and root out fraud in Washington, President Trump and his administration have frozen vast sums of dollars of congressionally appropriated funds. He has, without an official reason, fired at least four Senate-confirmed agency officials as well as 17 independent agency inspectors general. His subordinates have gutted two federal agencies.

Are these actions legal? Dozens of lawsuits are probing the questions. Legal scholars disagree on how the cases could turn out. But they tend to agree that if the actions the Trump administration is taking are extreme, they are also, in another sense, predictable.

Why We Wrote This

A story focused onPresidential power has steadily expanded over the past century. Under the Trump administration, the Supreme Court will face questions about the bounds of that expansion.

The past century has been marked by a steady expansion of presidential power. As heads of the most nimble and proactive branch of government, the United States’ chief executives have sought greater authority. As the U.S. has become a superpower in a fast-paced, globalized world, Congress and the judiciary have willingly delegated this power. The U.S. Supreme Court punctuated the trend last year when it ruled that former presidents are mostly immune from criminal prosecution.

The president is unique in our system of government, Chief Justice John Roberts asserted in that decision. “Unlike anyone else,” he wrote, “the president is a branch of government.”

The public, however, seems wary. According to a Pew Research Center survey published last week, 78% of Americans say it would be “too risky” to expand presidential power. Now, as President Trump is claiming even more power for the executive branch, the justices face the foundational question: Just how much power should that branch – should that person – have?

The founders’ vision

The first sentence in Article 2 of the Constitution says the executive power “shall be vested in” the president. Beyond that, it articulates a few specific powers, including the power to make treaties and appoint “officers of the United States.”

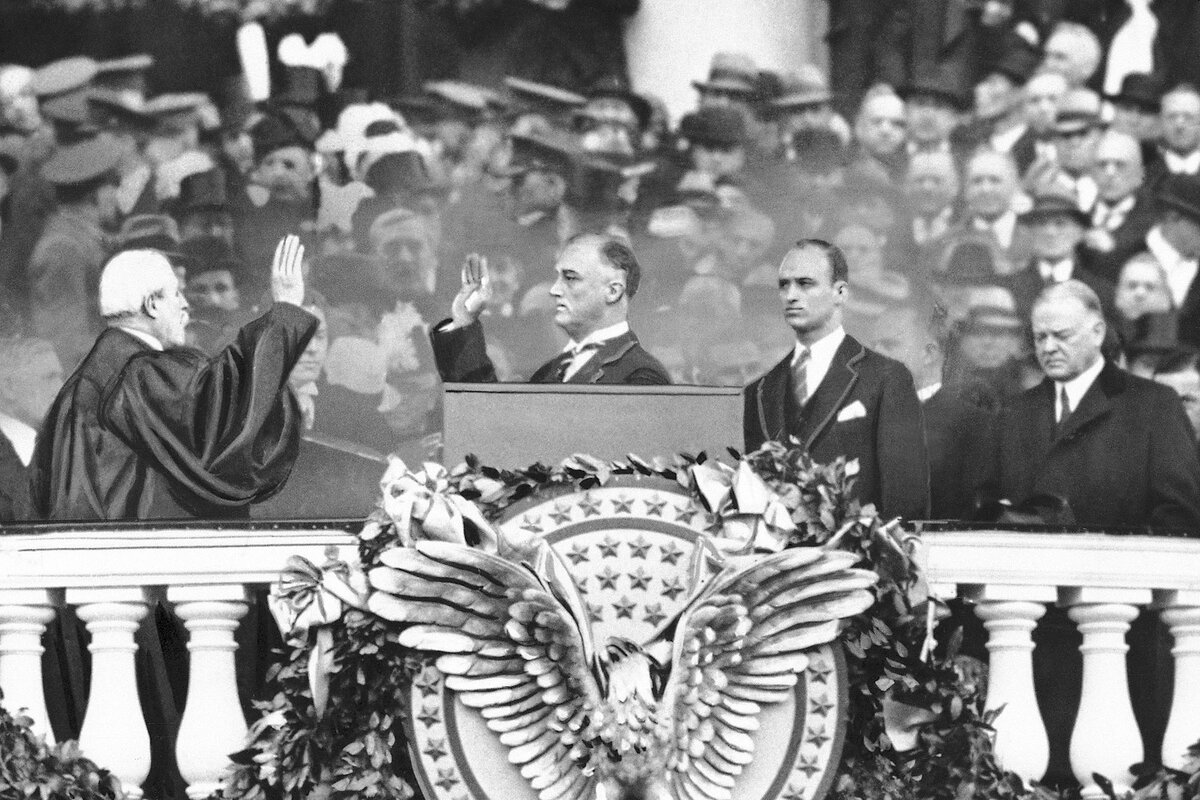

For more than 100 years, the presidency was relatively constrained. But at the turn of the 20th century, that began to change. President Theodore Roosevelt asserted that he had the right to all powers not explicitly denied him. Decades later, President Franklin D. Roosevelt transformed Americans’ views of what the president could – or should – do with a flurry of actions in his first 100 days.

As America has modernized and become a global superpower, its executive branch has grown in power and physical size. A branch that in 1789 had five Cabinet members and one federal agency now includes 16 Cabinet members and hundreds of federal agencies. Between 1940 and 2014, the number of civilian employees in the branch more than tripled.

Conservatives have long criticized this expansion, arguing that federal agencies are now a de facto fourth branch of government – and one that is unelected and unaccountable to the public. While some presidents have tried over the years to trim layers of government workers, President Trump is now attempting to exert more control over these federal agencies, arguing that it’s necessary to fulfill a campaign promise to reduce waste and eliminate government fraud.

“We are returning to the founders’ vision for what government ought to look like,” says Daniel Suhr, president of the Center for American Rights, a conservative legal organization. “That is the president at the top of the executive branch, and the officers under him being responsible to follow through on the policy direction he gives.”

DOGE-ing government

Mr. Trump’s efforts are being led by what he has named the Department of Government Efficiency (DOGE), a temporary agency he created without congressional approval and that he alone oversees. Elon Musk, the world’s richest man, is a key adviser on this executive branch shakeup. (After his election, the president tapped Mr. Musk to lead the agency, but the administration has suggested in a new court filing that, legally, Mr. Musk is not affiliated with DOGE.)

Those efforts have translated into some unprecedented, controversial moves not just from the executive branch but also from the president himself.

Over the past month, Trump officials have effectively shuttered the U.S. Agency for International Development and the U.S. Consumer Financial Protection Bureau. His administration has frozen hundreds of millions of dollars in grants and funds approved by the legislature. President Trump fired at least four leaders of independent federal agencies and 17 agency watchdogs, though it’s unclear if he had the authority to do so.

On Tuesday, he signed another executive order asserting the president's direct control over agencies that have long been understood to be largely independent, such as the Federal Trade Commission and the Federal Communications Commission.

“Investigations of government structures and efficiencies have happened in the past,” says Mitchel Sollenberger, a political science professor at the University of Michigan-Dearborn. But with these latest Trump administration moves, “They’re stopping money; they’re restructuring ... departments,” he says. “I haven’t seen that before.”

An executive-friendly Supreme Court

Five people who have played a role in this expansion of executive power now sit on the Supreme Court.

Chief Justice Roberts and Justice Samuel Alito, for example, worked in the U.S. Justice Department under President Ronald Reagan. Justice Elena Kagan was a top DOJ official under President Barack Obama. And Justices Neil Gorsuch and Brett Kavanaugh both worked in the George W. Bush administration, the former as a DOJ official and the latter as a White House official.

No members of the court have much legislative experience, however. That means “They come with a probably unavoidable – because they’re human – impulse to give more weight to interests they find familiar or recognizable,” says Aziz Huq, a University of Chicago Law School professor.

When determining if a branch of government is trying to usurp the authority of other branches, they’re likely “giving more weight to the executive than to Congress because they’re more familiar with what it means to work in the executive,” he adds.

This may explain, in part, the court’s unprecedented ruling on presidential immunity last year. Chief Justice Roberts, a former DOJ and White House lawyer, wrote that fear of prosecution would overly burden the “‘vigor’ and ‘energy’” of the president. That sentence quoted Alexander Hamilton, an early advocate for a strong presidency.

The president doesn’t have “an unlimited grant of power,” says Mr. Suhr of the Center for American Rights. But what “the Supreme Court has reminded us in the past decade is [that] the president is the executive branch, and he has the right to control his branch and his appointees.”

In an effort to gain more direct control over the executive branch, some of Mr. Trump’s recent actions seem to directly challenge these separation-of-powers concerns. The administration Feb. 16, for example, asked the high court to uphold the president's firing of the head of an independent agency that protects government whistleblowers.

Courts will be weighing in on other assertions of presidential power in the coming weeks and months.

The Supreme Court has said the president can fire certain federal agency leaders, for example. But does that mean he can unilaterally fire leaders at independent agencies like the Federal Election Commission or the National Labor Relations Board, as he did earlier this month?

Last year the court rejected a challenge seeking to shut down the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, holding that its funding mechanism is constitutional. So can DOGE effectively shutter the agency by limiting its funding and pausing its activities?

By law, the executive branch can only “impound” certain funds and must otherwise spend money as appropriated by Congress. What does that mean for the freeze on federal grants?

So while some of Mr. Trump’s actions may be considered “a continuation” of the decadeslong expansion of presidential power, says Professor Huq, others are “so comprehensive that it’s hard not to see [them] as a claim for a fundamentally different kind of constitutional order.”

Last summer brought a landmark ruling from the Supreme Court expanding the limits of presidential power.

This summer could well bring another one.

Editor's note: This story was updated on Feb. 19, the day of initial publication, to reflect an additional Trump executive order. On Feb. 21 the article was updated again, placing that news lower in the article and shortening how it is described.