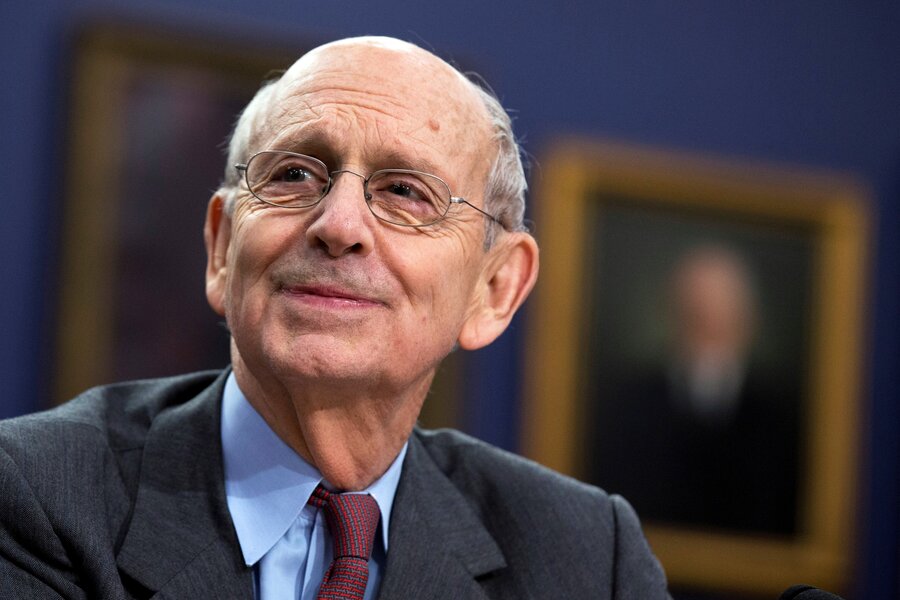

Justice Breyer, a pragmatic bridge builder, set to retire

Loading...

| Washington

Liberal Supreme Court Justice Stephen Breyer is retiring, giving President Joe Biden an opening he has pledged to fill by naming the first Black woman to the high court.

Justice Breyer, 83, has been a pragmatic force on a court that has grown increasingly conservative in recent years, trying to forge majorities with more moderate justices right and left of center.

Two sources told The Associated Press the news, speaking on condition of anonymity so as not to preempt Justice Breyer’s eventual announcement. NBC first reported the justice’s plans.

Justice Breyer has been a justice since 1994, appointed by President Bill Clinton. Along with the late Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg, Mr. Breyer opted not to step down the last time the Democrats controlled the White House and the Senate during Barack Obama’s presidency. Justice Ginsburg died in September 2020, and then-President Donald Trump filled the vacancy with a conservative justice, Amy Coney Barrett.

Justice Breyer’s departure, expected over the summer, won’t change the 6-3 conservative advantage on the court because his replacement will be nominated by President Biden and almost certainly confirmed by a Senate where Democrats have the slimmest majority. It also will make conservative Justice Clarence Thomas the oldest member of the court. Mr. Thomas turns 74 in June.

Senate Majority Leader Chuck Schumer said Mr. Biden’s nominee “will receive a prompt hearing in the Senate Judiciary Committee and will be considered and confirmed by the full United States Senate with all deliberate speed.”

Republicans who changed the Senate rules during the Trump era to allow simple majority confirmation of Supreme Court nominees appeared resigned to the outcome.

Sen. Lindsey Graham of South Carolina, the top Republican on the Senate Judiciary Committee, said in a statement: “If all Democrats hang together – which I expect they will – they have the power to replace Justice Breyer in 2022 without one Republican vote in support.”

Liberal interest groups expressed relief. They had been clamoring for Justice Breyer’s retirement for the past year, concerned about confirmation troubles if Republicans retake the Senate.

“Justice Breyer’s retirement is coming not a moment too soon, but now we must make sure our party remains united in support of confirming his successor,” Demand Justice Executive Director Brian Fallon said.

Among the names being circulated as potential nominees are California Supreme Court Justice Leondra Kruger, U.S. Circuit Judge Ketanji Brown Jackson, prominent civil rights lawyer Sherrilyn Ifill, and U.S. District Judge Michelle Childs, whom Mr. Biden has nominated to be an appeals court judge. Ms. Childs is a favorite of Rep. James Clyburn, D-S.C., who made a crucial endorsement of Mr. Biden just before South Carolina’s presidential primary in 2020.

Mr. Biden has been focused on filling federal judicial nominations with a more diverse group of judges, and the Supreme Court has not been top of mind during his first year in office, according to White House aides and allies. A decision on a nominee has not been made yet, they said, and is expected to take a few weeks. But Mr. Biden has expanded his pool of applicants by naming more Black women to the bench.

White House press secretary Jen Psaki said on Twitter: “It has always been the decision of any Supreme Court Justice if and when they decide to retire, and how they want to announce it, and that remains the case today. We have no additional details or information to share from @WhiteHouse.”

Often overshadowed by his fellow liberal Justice Ginsburg, Justice Breyer authored two major opinions in support of abortion rights on a court closely divided over the issue, and he laid out his growing discomfort with the death penalty in a series of dissenting opinions in recent years.

Justice Breyer’s views on displaying the Ten Commandments on government property illustrate his search for a middle ground. He was the only member of the court in the majority in both cases in 2005 that barred Ten Commandments displays in two Kentucky courthouses but allowed one to remain on the grounds of the state Capitol in Austin, Texas.

In more than 27 years on the court, Justice Breyer has been an active and cheerful questioner during arguments, a frequent public speaker and quick with a joke, often at his own expense. He made a good natured appearance on a humorous National Public Radio program in 2007, failing to answer obscure questions about pop stars.

He is known for his elaborate, at times far-fetched, hypothetical questions to lawyers during arguments and he sometimes has had the air of an absent-minded professor. He taught antitrust law at Harvard earlier in his professional career.

He also spent time working for the late Sen. Edward Kennedy when the Massachusetts Democrat was chairman of the Senate Judiciary Committee. That experience, Justice Breyer said, made him a firm believer in compromise.

Still, he could write fierce dissents, as he did in the Bush v. Gore case that effectively decided the 2000 election in favor of Republican George W. Bush. Justice Breyer unsuccessfully urged his colleagues to return the case to the Florida courts so they could create “a constitutionally proper contest” by which to decide the winner.

And at the end of a trying term in June 2007 in which he found himself on the losing end of roughly two dozen 5-4 rulings, his frustrations bubbled over as he summarized his dissent from a decision that invalidated public school integration plans.

“It is not often that so few have so quickly changed so much,” Justice Breyer said in a packed courtroom, an ad-libbed line that was not part of his opinion.

His time working in the Senate led to his appointment by President Jimmy Carter as a federal appeals court judge in Boston, and he was confirmed with bipartisan support even after Mr. Carter’s defeat for reelection in 1980. Justice Breyer served for 14 years on the 1st U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals before moving up to the Supreme Court.

His 87-9 high-court confirmation was the last with fewer than 10 dissenting votes.

Justice Breyer’s opinions were notable because they never contained footnotes. He was warned off such a writing device by Arthur Goldberg, the Supreme Court justice for whom Justice Breyer clerked as a young lawyer.

“It is an important point to make if you believe, as I do, that the major function of an opinion is to explain to the audience of readers why it is that the court has reached that decision,” Justice Breyer once said. “It’s not to prove that you’re right. You can’t prove that you’re right; there is no such proof.”

Born in San Francisco, Justice Breyer became an Eagle Scout as a teenager and began a stellar academic career at Stanford, graduating with highest honors. He attended Oxford, where he received first-class honors in philosophy, politics, and economics.

Justice Breyer then attended Harvard Law School, where he worked on the Law Review and graduated with highest honors.

Justice Breyer’s first job after law school was as a law clerk to Mr. Goldberg. He then worked in the Justice Department’s antitrust division before splitting time as a Harvard law professor and a lawyer for the Senate Judiciary Committee.

Justice Breyer and his wife, Joanna, a psychologist and daughter of the late British Conservative leader John Blakenham, have three children – daughters Chloe and Nell and a son, Michael – and six grandchildren.

This story was reported by The Associated Press. AP writer Colleen Long contributed to this report. Mark Sherman reported from Bradenton Beach, Florida.