Outspoken death-row inmate calls Nevada’s bluff

Loading...

| Savannah, Ga.

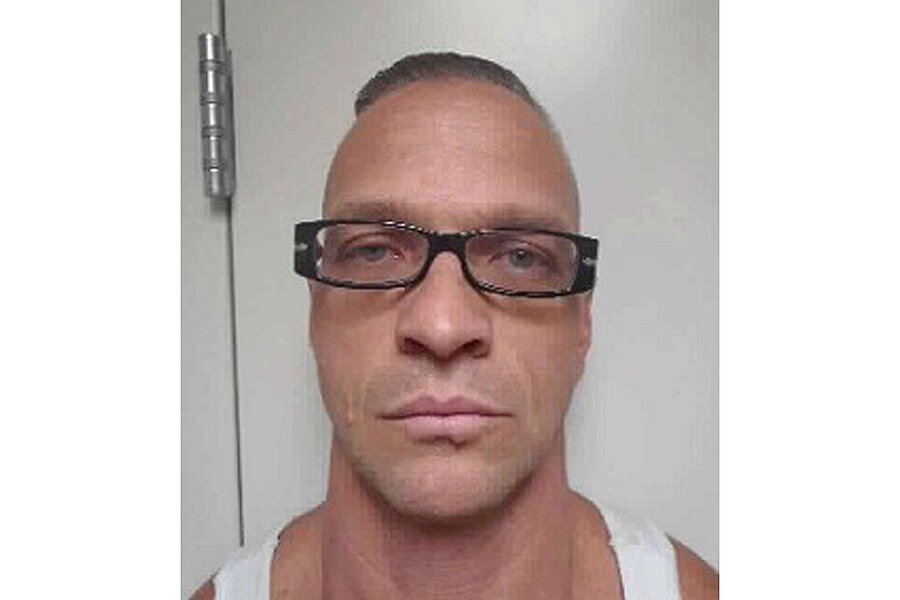

Scott Dozier would rather be executed than live on death row. So the double-murderer, imprisoned in Ely, Nev., is urging the state to kill him.

Mr. Dozier may be motivated, at least in part, by narcissism. Psychologists say he tends to portray his existence in mythical terms.

But he’s also calling the bluff of Nevada, which – like four other states with a death penalty – has virtually stopped carrying out capital punishment. Only those few inmates who “volunteer” to go forward with their punishment are actually executed. Nevada recently constructed a $1 million death chamber, but its last execution was in 2006. Such policies leave many inmates to spend years or even decades on death row.

Why We Wrote This

Scott Dozier’s case could push states that have retained the death penalty but have virtually stopped carrying it out to make a choice: Abolish it or find an acceptable method of execution.

“Life in prison isn’t a life,” Dozier told the Las Vegas Review-Journal recently.

Dozier came within hours of his death wish last week before a national uproar over botched lethal injections interceded, and a state judge issued an injunction to allow an 11th -hour lawsuit by drugmaker Alvogen.

“[Dozier] saw an opportunity to be the first execution in a dozen years, in the state’s new death chamber, and all these firsts could add to the myth,” says Vince Gonzales, a Dallas-based sentencing expert who studied Dozier, and at one point was hired by his defense team. “That came crashing down on him.”

The case could still have a profound influence, however, by forcing those states that have essentially held on to the death penalty in name only to make a choice: abolish the punishment, or find an acceptable means of carrying it out.

The case “is going to have reverberating effects across any death-penalty state using drugs or lethal injection,” says Deborah Denno, a Fordham University law professor and death penalty expert.

Partly because of his willingness to speak out, Dozier’s gambit has reinvigorated questions about volunteers: At what point does state-sponsored homicide become state-assisted suicide?

Equally important, the Alvogen lawsuit – one of the first in which a drugmaker is directly suing the state – has put a fresh spotlight on states’ decade-long scramble to procure effective compounds for lethal injections.

In that way, Dozier’s saga personifies what many Americans find to be ethical gaps in the death penalty.

Ethical debate over lethal injection

His case closely mirrors that of Gary Gilmore, who was likewise intelligent and artistic – and demanded that his death sentence be carried out quickly.

“This is my life and this is my death,” Gilmore said before facing a firing squad in 1977, making him the first to be executed after the Supreme Court reinstated the death penalty in 1976.

If Gilmore’s volunteerism defined the beginning of the modern death penalty era, Dozier’s may turn out to be the coda.

The number of executions across the United States fell to a 25-year low in 2017, and capital sentencing waned even in Texas, the nation’s leading execution state. That’s a reflection in part of growing bipartisan opposition not only to the death penalty, but also to the substances used to execute inmates.

That states are now turning to controversial drugs like fentanyl – a key driver of opioid overdoses – highlights the ethical dilemma.

“The legitimacy of capital punishment has for a long time been tied into the illusion that we would find a technologically advanced way to kill,” says Austin Sarat of Amherst College in Massachusetts who has studied the death penalty for more than four decades.

But in fact, former methods of execution are making a comeback.

In Tennessee, which is facing a challenge to its lethal concoction by 33 death-row inmates, the legislature has given the governor power to make the electric chair the primary rather than secondary method of execution.

The gas chamber, introduced in Nevada in the 1920s but since retired, could return in Oklahoma – which seeks to bypass the lethal injection crisis and use nitrogen gas.

“It was supposed to be more humane than the firing squad or hanging,” says Michael Greene, a history professor at the University of Nevada, Las Vegas. “Well, now we look at [the gas chamber] and ask again: Is that barbaric? We are deciding what we think is barbaric in our time.”

In support of the death penalty

Some death-penalty proponents say the gas chamber would be most effective and humane. But they are concerned that the debate is straying irresponsibly away from victims, their families, the law, and juries – and focusing instead on the wishes of the killers.

At Dozier’s trial, family members testified in support of giving him the death penalty.

“We lost our innocence, our ignorance, our calm, quiet lives,” said Kimarie Miller, whose brother, Jeremiah Miller, was killed and dismembered by Dozier.

Dozier’s death sentence “has been imposed and should be carried out, and right now we're allowing appeals [and legal challenges] to drag on much too long ... when there is no question of guilt,” says Kent Scheidegger, director of the Criminal Justice Legal Foundation in Sacramento, Calif.

But Dozier’s stance challenges the assumption that death would be the worst punishment, offering a paradoxical glimpse into a death-penalty system where a shrinking number of US counties are sending convicts to death row.

“Most people think these inmates are fighting for their lives and the way to really get back at them is to kill them,” says Fordham’s Prof. Denno. “But here we have someone ... who is rubbing that in people’s faces and saying, ‘Do you want me to suffer? Then let me live.’ ”