Room for compromise on voter ID laws?

Loading...

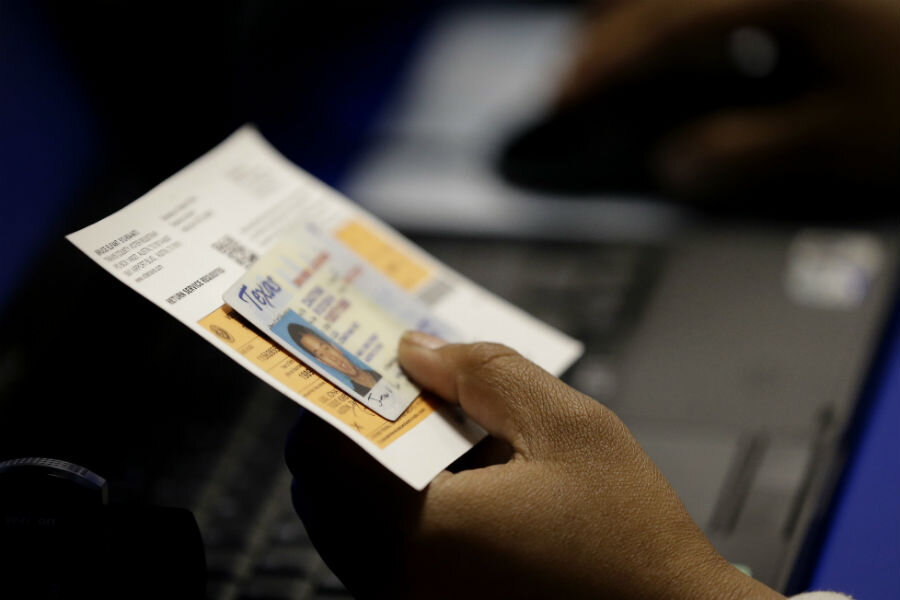

Federal courts have dealt a string of setbacks to new laws in several states imposing additional identification requirements on voters.

It’s an issue that arouses the passions of both parties’ bases – especially among those who connect it most keenly with the history of voter suppression among minorities – and one of supreme importance for the health of any democracy.

Yet there may be less distance between the two sides on policy than one might think.

In Texas, where one of the nation’s most restrictive voter-ID laws was struck down last month, district judge Nelva Gonzales Ramos rejected a request by the state’s attorney general to postpone hearings on whether the law had been enacted with the intention of discriminating against minority voters. The delay sought by Texas Attorney General Ken Paxton, which would have put off the first hearing until at least next August, could influence results in local elections held in the interim, wrote Judge Ramos.

Several states have seen verdicts against additional voter-ID requirements this summer. In one, North Carolina, a judge ruled that a state law that also banned same-day registration and out-of-precinct voting had targeted African-American voters with “almost surgical precision.” And in a decision that echoes the findings of several national-scale studies, a North Dakota court said evidence showed that “voter fraud in North Dakota has been virtually non-existent.”

A 2013 US Supreme Court decision in Shelby County v. Holder opened the floodgates of voter-ID laws by eliminating requirements that certain states clear new electoral measures with the federal government before implementing them. Since then, 34 states have passed legislation, according to the National Conference of State Legislatures (NCSL).

Some Republican proponents point to ID requirements for other everyday activities, like cashing checks or boarding planes, to support voting ID laws. The staunchest of them, like Kansas Secretary of State Kris Kobach, link it to perceived threats posed by undocumented immigration. Others simply ask what the big deal is.

The most recent court decisions may show, however, that evidence is mounting on the side of those who see further requirements as a way to suppress the vote among minorities, the poor, and other groups that tend to elect Democrats.

“They really do not protect our nation in any meaningful way and instead deter voters from turning out to polls and casting a vote when they do,” says Janai Nelson, associate director-counsel at the NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund, in a telephone interview with The Christian Science Monitor.

Ms. Nelson, who helped litigate a lower-court challenge to the Texas law, said the measures called for by the judge in that case were “imperfect but helpful” examples of compromise, often overlooked in an impassioned debate.

“We should be looking for ways to ensure that our voters are who they say they are but also to make sure that the ID being requested is sensible,” she says.

Some of the new state requirements are less burdensome than others: Roughly half do not require a photo ID, and most of those are not particularly strict, according to an analysis by the NCSL.

“The really strict ones, like the one Texas passed, are much more harmful than the non-strict ones,” says Dan Tokaji, a professor at Ohio State University’s Moritz College of Law. “If you’ve got a rule that you have to show non-photo ID or sign an affidavit verifying ID if you don’t have it, that’s not likely to exclude many voters.”

Dr. Tokaji tells the Monitor that one model of compromise might exchange a “reasonable” national ID requirement for federal elections, as sought by Republicans, for a Democrat-friendly reform broadening voter-registration rules, in order to expand voter participation.

“This debate has gone on for a really long time and it would be nice to have some sort of resolution to it,” he adds.

Editor's note: This article has been updated to correct the name of Janai Nelson's organization. The NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund has been separate from the NAACP since 1957.