Why Seattle is scoring victories against labor traffickers

Loading...

This story was written to be viewed on the Monitor's long-form platform.

SEATTLE – Millions of people are trapped in some version of forced labor worldwide, yet few perpetrators are ever prosecuted.

Even in the US, with its well-oiled legal system, successful criminal cases are few and far between. But here in Seattle, a small antitrafficking team is showing how legal action can be effective when when detectives, prosecutors, and social workers learn to collaborate.

Cases of trafficking rarely get to court. Often the victims don’t want to testify, or authorities don’t recognize the offenses as human trafficking. And labor trafficking cases outside the sex trade, where victims are more easily identified, can be tougher to crack.

Yet in Washington State, successful prosecutions over the past decade include:

- A flooring contractor entering a guilty plea for smuggling a Mexican immigrant into the country and then coercing him to work 15-hour days installing carpets to repay his smuggling fee.

- A Moroccan couple pleading guilty to bringing in their 12-year-old niece from Morocco on a visitor’s visa, then pressing her into long days of service in the couple’s home and coffee shop.

- A Micronesian couple getting years in prison after admitting similar treatment of a young cousin who was forced to work in the home and a nearby poultry plant.

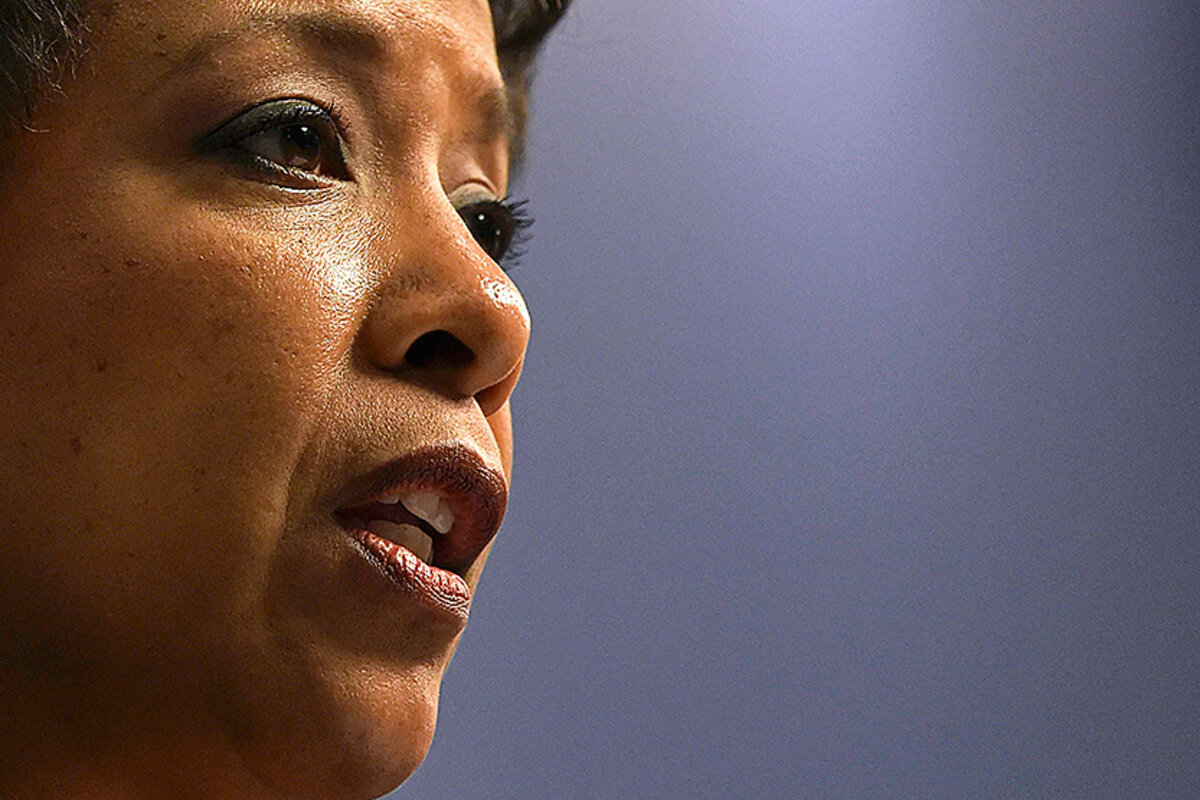

In September, US Attorney General Loretta Lynch, on a visit here, called the Seattle antitrafficking task force an “extraordinary partnership” that in a decade of operations had investigated more than 140 cases of potential human trafficking and prosecuted 60 of those.

That may not sound like much. In reality, it’s well above average for a prosecutorial district and is based on a steady drumbeat of labor trafficking convictions, averaging one a year. Many are difficult to investigate, often turning on the testimony of a single survivor.

“Cases rise and fall on the victim,” says Kate Crisham, an assistant US attorney who is a co-chair of the task force, in a district representing about 5 million people in western Washington.

What is the special sauce? And can some lessons from Seattle be applied more broadly to punish and deter those who profit from modern-day slavery?

A first step is creating a robust cross-agency team that does what police departments acting alone often cannot do. The task force in Washington State was set up in 2004, tapping federal grants that resulted from a landmark 2000 antitrafficking law. Last year, that yielded $1.5 million in Justice Dept grants.

A second factor is mutual respect among participants – something that doesn’t flow automatically from forming a task force.

Kirsten Foot, a University of Washington communication professor and author of “Collaborating Against Human Trafficking,” says the Seattle-based team has managed to bridge the worlds of nongovernment organizations (NGOs) and diverse law enforcement agencies. Where antitrafficking efforts in some other cities have broken down, the members of this team “have come back to the table” after setbacks.

Ask Ms. Crisham, and she’ll tell you that another key to success has been for law enforcement to put trafficking victims at the center of the process. This means helping victims rebuild their lives first, and seeing if they want to testify later. Some may refuse to join a lawsuit, but others will, and criminologists say this strategy is the best route to successful prosecutions.

$90,000 in missing wages

The case of one Filipina trafficking victim shows how Seattle’s approach served both the goal of punishing offenders and the desire of victims for restoration. In April 2010, this woman in her 50s – identified by her initials S.A. – had broken loose from a family that had lured her to the country and held her in near isolation for more than four years.

“She was very scared,” says Kathleen Morris, one of the people who assisted her as a victim advocate. “She would just shake.”

S.A. was concerned for her safety, her freedom, and the wellbeing of her children back in the Philippines, says Ms. Morris, a co-chair of the Washington Advisory Committee on Trafficking (WashACT), its official title. She wanted to claim financial and medical support as a trafficking victim. But she wasn’t interested in legal recourse.

Meanwhile, WashACT’s two full-time investigators worked the case, confirming that S.A. wasn’t known to neighbors at the houses in Washington and California where she had worked. S.A. said she was paid $400 a month and wasn’t allowed to talk to anyone other than her employers.

“In some ways, the fact that [neighbors] didn’t see the woman... is evidence to us,” says Assistant US Attorney Ye-Ting Woo.

Finally the investigators told S.A. that they could only move the case toward prosecution with her as a witness. S.A. now decided she wanted to testify. As time passed, she had become more interested in restitution and less fearful about going public.

In 2014 she won some $90,446 in missing wages – and the moral victory of seeing Romulo Almeda, her former captor, say in a plea bargain agreement that he was guilty of a federal crime.

S.A., like so many labor trafficking victims, had been afraid to seek help from authorities because she believed she’d be in trouble with the law due to her expired work visa. Today, her helpers say she’s won legal status, through a T visa for trafficking victims, in the US and is working as a nurse.

“She’s feeling like, ‘I am finally a person, because for so many years I was invisible,” says Ms. Woo, who prosecuted the case.

A question of trust

The cases taken up by WashACT span from cosmopolitan Seattle to Longview, an industrial city near the Oregon border. As in other jurisdictions, labor trafficking occurs in the shadows of people’s daily lives, from farms to factories to restaurants and nail salons.

The cases don’t all go smoothly. And they rarely go quickly. However, Amy Farrell, a criminologist at Northeastern University in Boston, says prosecutions of labor trafficking are much more likely when a task force includes NGO victim services along with law enforcement.

Currently, 16 regional task forces – including WashACT – receive Justice Department funding for what it calls an “enhanced collaborative model” of helping victims and investigating cases. The Justice Department also has set up federal antitrafficking forces in some large cities.

One recurring point of tension in this model is that NGOs question whether partnerships with police will serve victim needs, while cops fret that victim advocates may discourage survivors from reporting crimes. Still, many in law enforcement have come to embrace this approach.

“Without the services that NGOs provide, victims aren’t necessarily going to find the stability that allows them to move forward with the investigation,” says Jennifer Williams, a special agent with the Department of Homeland Security, who worked on S.A.’s case. “That’s huge.”

Ms. Foot says some task forces have broken down over difficulties building trust. And the Justice Department is funding fewer such initiatives, down from a peak of 42 five years ago. This regrouping was driven by budget cuts, plus a recognition that some task forces hadn’t proven effective.

One reason why Seattle has succeeded, says Foot, is that participants agreed on written ground rules, including confidentiality for victims assisted by NGOs, even if the initial referral comes from police.

WashACT members are among the contributors to a Justice Department guidebook for law enforcement agencies in other cities or states setting up their own task forces. Members have also been tapped to train detectives in conducting trafficking investigations and cross-agency teamwork.

And the collaboration here has continued despite turnover in all three leadership positions in WashACT (the group has an NGO official, a federal prosecutor, and a police representative as co-chairs). “They have succeeded in continuing to build trust,” Foot says. “It has to be rebuilt every time there’s a personnel change.”

It may have helped that some players on the team bring extra layers of experience to their posts. Woo, who helped launch the Seattle task force, had a degree in social work. Seattle Police Detective Megan Bruneau, similarly, is the daughter of a county prosecutor and worked as a victim advocate before joining the police, initially as a beat cop.

For all its successes, Seattle may be simply scratching the surface of labor trafficking. One drawback is that most cases are “reactive”: A victim escapes and then talks to police. To fully tackle the problem, say experts, cops also need to catch crimes in progress.

Farrell, the Northeastern criminologist, says a key need is to train and motivate other government agencies – like licensing and inspection officials who visit farms or restaurants – so they can give more tips to law enforcement.

“Labor trafficking cases are so hard to see in many ways, that it really takes people being trained to identify them, and going into the spaces where they exist, which are often under-regulated parts of the economy,” she says.

‘Don’t be a hero’

On a recent evening, Ms. Bruneau navigates the bustling, rain-slicked streets of Seattle, not in a squad car but in a rental suited to her frequent undercover work. She has just finished a busy shift, including interviewing a witness in a promising new trafficking case and conferring with Crisham about how to proceed.

Now, Ms. Bruneau enters the local office of the International Rescue Committee, not far from the city’s waterfront and the Seahawks’ CenturyLink Field.

The event is an open-to-all seminar on how to spot labor trafficking and how to respond. Attendees, who have squeezed into a modest meeting room, include social workers and city and county employees. Bruneau, Morris, and Crisham give a tour of the problem and the efforts to solve it. Soon the audience starts asking what exactly they can do to help.

“Don’t be a hero,” Bruneau says, noting that amateur efforts to be a rescuer can actually backfire by putting people at risk.

But she encourages people to call in tips, and gives examples. “Every day a van drives workers to the back entrance of a restaurant. They don’t look happy. That’s worth us looking into.”