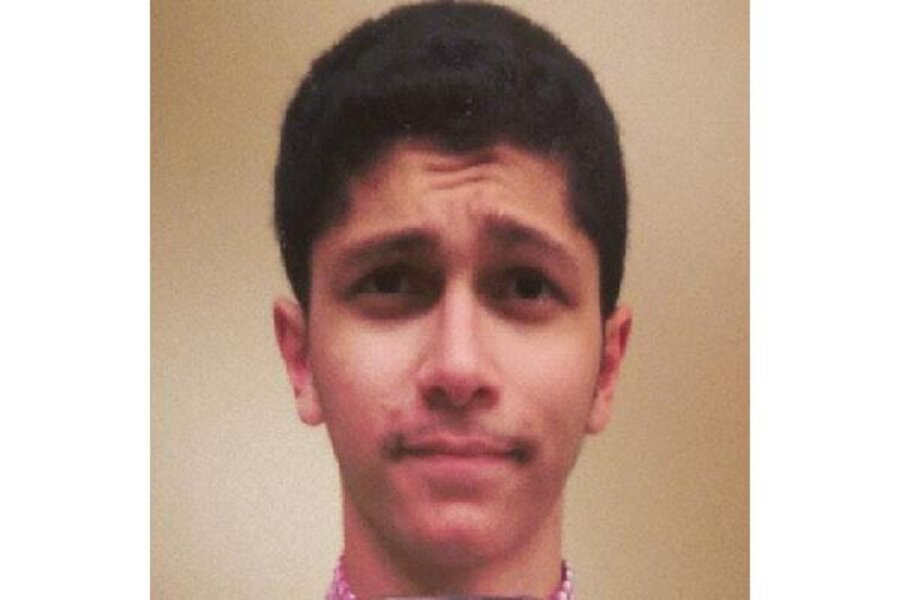

One Virginia teen's journey from ISIS rock star to incarceration

Loading...

| Washington

On Twitter, Ali Shukri Amin was on his way to becoming a giant within the online jihadist community.

Under the alias @Amreekiwitness, the Virginia teenager pumped out more than 7,000 tweets in support of the self-proclaimed Islamic State and its radical agenda.

In one of his best-known pranks, he superimposed the group’s iconic black banner onto the flagpole atop the White House in an online image. He heralded the organization’s “upcoming conquest of the Americas.”

Within three months, Ali had 4,000 followers, including active fighters and recruiters in Syria and Iraq. This was a big, big deal for a high school student in suburban America.

Until his arrest.

On Aug. 28, standing before a judge at the federal courthouse in Alexandria, Va., the teenager looked decidedly small, almost frail, hunched over in his jail-issued navy blue coveralls.

Behind him in the gallery were three solid rows of extended family members, the women in headscarves. They sat silently, some clutching tissues, as the judge announced his decision.

The 17-year-old was sentenced to serve 11 years in prison, pay a $100,000 fine, and submit to federal supervision for the rest of his life, including government monitoring of his Internet activities.

Defense attorney Joe Flood told the judge his client was a confused teen looking for guidance from adults in his life, including religious leaders, but wasn’t getting answers.

“The Internet gave him answers,” Mr. Flood said. “Albeit the wrong ones.”

The rise and precipitous fall of Ali Shukri Amin marks a tragedy for one extended family in northern Virginia. In a larger sense, his radicalization through his prolific use of social media represents a cautionary tale for every American teenager and every parent of an American teenager.

Radicalization by a foreign terror organization is one more thing to add to an already long list of predatory risks for young people surfing the web.

It is hard to believe that a Mideast-based terror group that celebrates sexual slavery and beheadings would appeal to someone with all the advantages of a bright and articulate American teen.

But Ali’s case demonstrates the growing ability of groups like the Islamic State organization to use social media to identify vulnerable young people, befriend them, indoctrinate them, and finally recruit them into taking supportive action.

Ali is one of 58 individuals arrested in 2015 on charges of providing material support to militant Islamic groups. Another 250 people are believed to have made it to Syria, according to the US government.

His case highlights the extent to which such groups are successfully reaching out to young minds – including teens in the United States – for support and fighters.

Ali’s experience, outlined in FBI affidavits and other court filings, offers a vivid illustration not only of how such radicalization happens, but also how difficult it can be to pull someone back once they start down the path toward extremism.

By all accounts, Ali is intelligent and articulate. He was an honors student at Osborn Park High School and had been accepted to the engineering program this fall at Virginia Commonwealth University. Now, instead of joining the freshman class, he’ll be finding his place in a prison cell in North Carolina.

The portrait of Ali that emerges from court documents is of a socially-isolated and awkward teenager who struggled with significant health issues, small stature, and an overprotective mother who had him sleep beside her until he was 13.

Ali did not participate in school sports, but he was smart and a good student. At 16, he was accepted into a prestigious curriculum for gifted students run by George Mason University. An acute medical problem forced him to miss classes for a number of weeks. He was unable to catch up and, in a huge blow to his self esteem, he was dropped from the program.

Online 'friends' 'treated me with respect'

After returning to classes at his old high school, Ali turned to the Internet for support and reassurance to counter his mounting frustration. He had been exploring his Muslim heritage and tried to connect with local religious leaders in Virginia. They wouldn’t discuss the issues that interested him and refused to engage in vigorous political debate, he said in a three-page letter to the judge.

He wanted to know why more wasn’t being done to help innocent Muslims being killed in Syria. He questioned whether he, as a Muslim, was obligated to participate in “jihad” to protect them.

“The adults in my life could not provide adequate answers or seemed too busy to try, and this included several respected imams who engaged me briefly, but always were too busy,” he said.

“In the absence of a constructive dialogue about my religious obligations with adults that I respected, I began to correspond with a number of people on the Internet who filled the gaps and provided increasingly radical answers to my questions,” he wrote.

It wasn’t just question and answer. His new online associates encouraged him to demonstrate the depth of his religious conviction by posting his own comments on the Internet. Eventually, they began to urge him to advocate for violent jihad.

“Developing these relationships became very important to me because several of these ‘friends’ treated me with respect and occasionally reverence,” he said. “For the first time I felt that I was not only being taken seriously about very important and weighty topics, but was actually being asked for guidance.”

At the time, Ali was 16 years old.

That’s when he started his Twitter account and began proselytizing.

“I began to feel I was making an important contribution to a global movement that would result in a more just society for Muslims, and I was doing so by advocating what I believed were legitimate approaches based on Quran,” he said.

This was wrong, Ali told the judge at his sentencing. His advocacy for violence was unmoored from the central theology of Islam, he said.

The deeper he entered this Internet world of “virtual” struggle, the more disconnected he became from his family, his life, and his future, he said.

Amreeki Witness began to look for opportunities to spread his ideas. During the upheaval in Ferguson, Mo., he tweeted: “May Allah incite righteous jihad in Ferguson and guide its people to Islam,” according to the SITE Intelligence Group, which monitors jihadi activity on the Internet.

At one point during his proselytizing stage, Ali intervened in a debate on Twitter between someone with the US State Department’s “ThinkAgainTurnAway” anti-jihadist counter-propaganda program and a pro-jihadi Twitter user.

The ThinkAgain user tweeted that “those who follow #Bin Laden’s path will share his fate.” The post included a list of dead fighters.

According to the SITE Intelligence Group, Ali responded with this tweet: “these men are martyrs, insha’Allah, with their souls in pure ecstasy roaming the vastness of eternal paradise.”

The State Department replied that the fighters had slaughtered innocents.

“Slaughtered innocents?” Amin responded, according to the SITE report. “You mean like AbdurRahman al-Awlaki, the 16-year-old boy not involved with any militants? Or what about the thousands killed in drone strikes weekly that make the news? The thousands that don’t [make the news]?”

Two weeks after US-born militant cleric Anwar al-Awlaki was killed in a 2011 drone attack in Yemen, his 16-year-old son, also a US citizen, was killed in a different US drone attack while sitting at an open-air café in Yemen. No justification has been offered for the attack, although reports suggested it was a case of mistaken identity.

“You are nothing more than criminals who betray the Muslims you claim to defend across the globe, butchering them,” Ali said, according to SITE. “1.7 million in Iraq, hundreds of thousands in Afghanistan, left, right, everywhere. Only an ignoramus who knows nothing about American foreign policy or any Muslim country could accept your lies…”

The State Department was apparently not amused by Ali’s ferocious debating style on social media. US government tweeters responded repeatedly to Amreeki Witness, and then finally decided to take a different form of action against him. They e-mailed his mother, according to a narrative in Ali’s psychological report. (The report does not disclose how the State Department learned that Ali was Amreeki Witness.)

Nonetheless, the government e-mail provoked a second major upheaval in Ali’s life within a few months, according to the psychological report.

A parent's haunting question

Ali’s mother arranged for her son to consult with a local religious leader, but the intervention fizzled out when the two failed to make a genuine connection.

His mother doubled down by threatening to take away his computer. Under threat of losing access to his supportive circle within the cyber jihad, the teen moved out of his mother’s house and in with an uncle, where he stayed for two months.

During that period, he pushed deeper into the online jihadi community, forging close friendships with like-minded individuals in Finland, South Africa, and Britain, according to court documents. He created an online blog to instruct aspiring jihadists how to avoid the scrutiny of security services by using encryption and anonymity software.

He gave online instructions about how to use bitcoin to secretly transfer funds to support jihad.

He also began to associate with a student at his high school, Reza Niknejad, who was thinking about traveling to Syria to fight.

According to FBI affidavits, Ali facilitated a number of contacts over secure Internet connections to prepare the way for Mr. Niknejad’s journey.

On Jan. 14, Ali and another man drove Niknejad to the airport where he boarded a flight to Athens, with a stop in Istanbul. Niknejad got off the plane in Turkey and traveled to a border town to meet an Islamic State group contact who would help him cross into Syria.

Two days later, Ali received word that Niknejad had arrived in Syria.

It is not clear to what extent the Niknejad family had any hint that Reza, 18, was in the process of radicalizing in the months after graduating from high school. The family declined a request for an interview.

But it is clear from the voluminous documents released in Ali’s case that his mother and stepfather were well aware of his dangerous Internet activities more than a year before his arrest by the FBI.

They turned to a local religious leader and threatened to cut off his access to the Internet. But these and other attempts at intervention failed.

Throughout the ordeal, his mother faced a haunting question.

Should she do nothing and hope her son grew out of his radicalization phase, even though it might lead him to go to Syria to fight and die?

Or should she instead contact the FBI and face the prospect of having to talk to her son through prison bars for the next 10 to 20 years of his life?

This is a choice no parent should ever have to make. But most parents in this situation confront the exact same haunting question.

“While we are glad that Ali did not go abroad, we also feel very confused and conflicted about having played a role in him being arrested,” Ali’s mother, Amani Ibrahim, wrote in a letter to the judge.

Mrs. Ibrahim wrote that she was pleased when her son first became eager to learn more about Islam and turned to the Internet for answers.

“I never thought that letting him have access to the Internet by himself would put him at the risk of finding the wrong information about Islam and meeting the wrong people who may guide him to the wrong path,” she said in her letter. “I see now that I was not only naive, but had abandoned an important responsibility.”

“The fact that we reached out to the authorities is the only light in this tragedy,” she wrote, “but it is a light that burns too.”

The question haunting Ibrahim is likely also tormenting the parents of Reza Niknejad.

Federal prosecutors have charged Niknejad with conspiring to provide material support to a foreign terror group and conspiring to kill or injure Americans in a foreign country. If he returns to the US, he would face 20 or more years in federal prison.

Three weeks after he boarded the plane for his secret trip to Syria, Niknejad called the family home in Woodbridge, Va. He spoke to his mother.

According to court documents, he told her he was being treated well in the caliphate and that he was going to “fight against these people who oppress the Muslims.”

Then he told her something else. He promised his mother that he would see her again ... in heaven.

Monitor staff writer Linda Feldmann contributed to this report.

• Part 1, Monday: How doomsday Muslim cult is turning kids against parents

• Parts 2 & 3, Tuesday: One Virginia teen's journey from ISIS rock star to incarceration & Eight faces of ISIS in America

• Part 4, Wednesday: FBI tactics to unearth ISIS recruits: effective or entrapment?

• Part 5, Thursday: What draws women to ISIS

• Part 6, Friday: To turn tables on ISIS at home, start asking unsettling questions, expert says

• Part 7, Saturday: How to save kids from ISIS? Start with mom.