Judge clears 'Friendship 9,' who dared to sit at white lunch counter in 1961

Loading...

| Atlanta

Thirty days of hard labor in a rough South Carolina prison camp in 1961: That was one punishment for a black person daring to sit at McCrory’s white lunch counter in Rock Hill.

Nine young black men who took the punishment, instead of paying a $100 fine to the system that oppressed them, became known as the Friendship 9. Their “jail, no bail” statement resonated beyond South Carolina and galvanized what had been a hodgepodge protest movement.

On Wednesday, the surviving members accomplished another civil rights milestone. In a poignant redress in a country where race relations still chafe, the Friendship 9’s prison camp convictions were thrown out, their names officially cleared. To not forget what happened in the ’60s, however, the official courtroom records will still reflect the wrong committed against the men.

Sixteenth Circuit Solicitor Kevin Brackett and Circuit Court Judge John C. Hayes III – whose uncle sent the men to the prison camp – closed the case. In essence, writes Andrew Dys for The State newspaper in Columbia, S.C. the State of South Carolina is saying that “instead of handcuffs and shackles, prison bars and hard labor on a chain gang, these young black people were right and the state that made segregation the law was wrong.”

The ruling mirrors a concerted and ongoing effort by the Palmetto State to confront a racist past. In December, the state – which has a popular Indian-American governor, Nikki Haley (R), and the first black Republican senator from the South since Reconstruction, Sen. Tim Scott – vacated the sentence of George Stinney, a 14-year-old who was executed in 1944. A judge had found that the black boy’s due process rights had been severely violated.

In the case of the Friendship 9, the Rock Hill community and the entire state had officially apologized to the men for the ugly response to their integration bid, which took place after lunch-counter protests became popular in the Carolinas. But their trespassing and breach-of-the-peace charges remained enshrined and still official at the York County courthouse.

“The conviction all those years ago was an unjust conviction under an unjust law,” Mr. Brackett said last year after announcing he would seek a retrial to clear the men. This move "does not change the courage, the valor of these great men who stood up against segregation.... Their courage will always be a badge of honor. But it, legally, will vacate the convictions. This will right a wrong in a way that what they did will never be forgotten.”

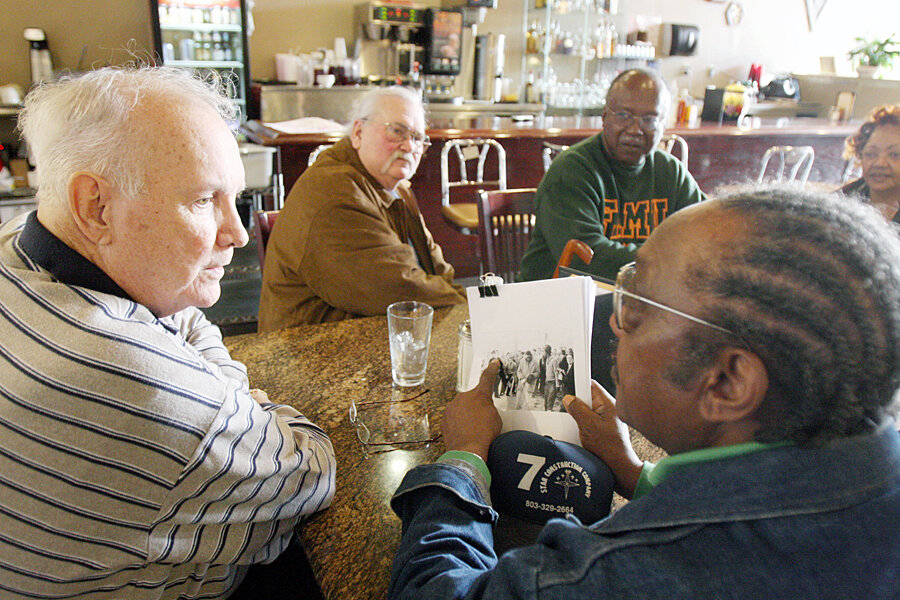

The legal pardon became a coda in a powerful parable about racism, regional reform, and forgiveness. Not only did a member of the original judge’s family reverse the ruling – "We cannot rewrite history, but we can right history," Judge Hayes said Wednesday – but in 2009, two white men who taunted the group in 1961 asked the men to forgive them after admitting their role in the episode.

One of the two men, a former Rock Hill police officer named Steve Coleman, confessed through tears at a meeting with members of the Friendship 9 that he was a slur-slinging teenager “in that crowd. I hollered along with the rest. I can remember the look of determination. Not on our faces. But yours. You know, I am sorry. Being raised in the South, you know how I was. But I’ve changed.”

The Friendship 9 are W.T. “Dub” Massey, Willie McCleod, Clarence Graham, David Williamson, James Wells, Mack Workman, John Gaines, Charles Taylor, and the late Robert McCullough, the acknowledged leader of the group.

The courtroom drama Wednesday was in legal terms a retrial. At the proceedings, Brackett made a motion to have the original sentences vacated because banning blacks from lunch counters was illegal. Hayes agreed.

"To have the records vacated essentially says that [the convictions] should have never happened in the first place," Kimberly Johnson, an author who pushed for clearing the men’s names after writing a children’s book about them, told The Associated Press.

Friendship 9 members traveled from all over the country to take part in the retrial on Wednesday. Mr. Graham said he hopes the group’s actions and the state’s acknowledgment of wrongdoing can still influence America’s struggle to fulfill the constitutional guarantee of equality.

"It's been a long wait," he said. "We are sure now that we made the right decision for the right reason.”

Rock Hill Mayor Doug Echols paraphrased a Robert F. Kennedy quote, noting before the proceedings that "few of us will have the greatness to be in history, as the Friendship 9 have done, but each of us can work to change a small portion of events within our own actions and, by example, touch the lives of others so that in the total of all of those acts, it will be confirmed and recorded that justice is for all people and that injustice must not be tolerated in any place at any time."