Should Mississippi execute its first woman in 70 years?

Loading...

| Atlanta

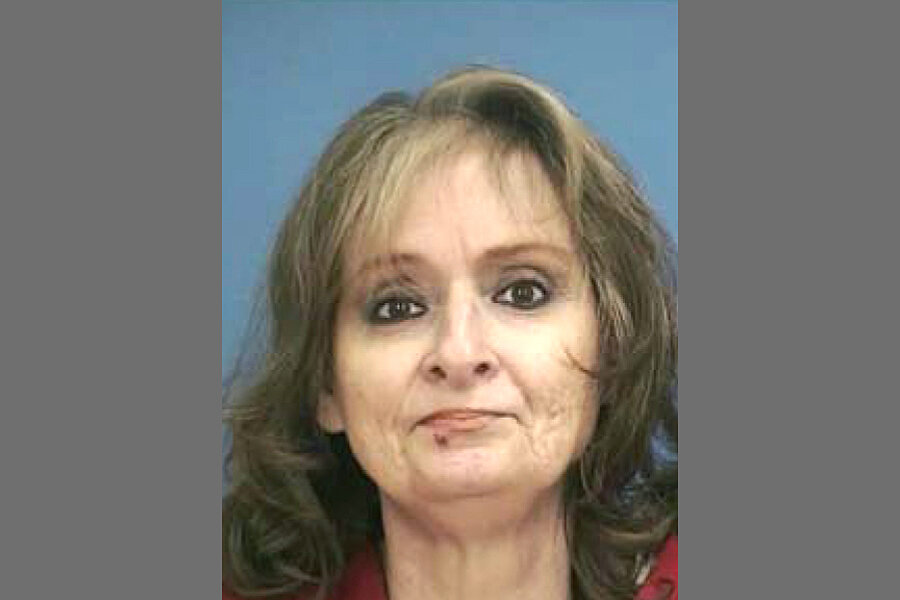

Despite the evidence that led a jury to conclude that Michelle Byrom masterminded a plot to kill her husband, the fact that the former lounge dancer may now face execution “just feels wrong,” former Mississippi Supreme Court justice Oliver Diaz has written.

In 2000, Ms. Byrom was convicted of capital murder for a role in the death of Edward Byrom Sr., sending her to Mississippi’s death row. Two co-defendants, including her son, Edward Byrom Jr., the triggerman, received less than 10 years in prison after they agreed to become witnesses for the state.

Now, as the execution looms, Mississippi faces a choice that critics contend could reflect on the US justice system more broadly: Should the state execute a woman said to have mental illness and an abusive past who, as Jackson (Miss.) Free Press columnist Ronni Mott opined, “did not commit the crime she’s convicted of”?

Mississippi has not executed a woman in 70 years.

To prosecutors and judges in the state, Byrom’s conviction is based on facts and confessions that come to one conclusion: She was an angry, bitter spouse who wanted her husband out of the way so she could cash a life insurance policy.

To critics, however, the courts have failed to halt a travesty. Wrapped up in the last-minute legal wrangling over Byrom’s fate are society’s changing views of abused women, questions about the effectiveness of appeals courts in ferreting out injustice, and general queasiness about the execution of women.

“If you read Mississippi's briefs in this case, and if you read the rulings of the state and federal courts that have defended this reedy result, you come to an inescapable conclusion: the state, and the judiciary, don't want to go back and look at what is under the rock of this case,” writes Andrew Cohen of The Atlantic, in an in-depth look at the legal proceedings over the years.

Despite a series of appeals that point out troubling problems with how the trial was handled, state and federal appellate judges have upheld the verdict.

Mississippi’s attorney general, Jim Hood, requested a March 27 execution date for Byrom, who is in her late 50s. Such dates have to be approved by the state Supreme Court, but on Thursday, it did not give approval, with no explanation.

Mr. Hood subsequently commented that such a response by the court usually means it will hear motions about the case. Byrom has been pleading for a hearing to introduce new evidence.

The main problem with the case, critics say, is that Byrom received poor counsel during the trial, including the decision by defense attorneys to exclude psychiatrist Keith Caruso. He said in a post-trial affidavit that he would have testified that Byrom was “psychologically unable to leave the abusive relationship with her husband."

Dr. Caruso, as well as a psychologist, has also judged Byrom to be mentally ill, and they testified in affidavits about her being violently and sexually abused as a child.

Critics, including Mr. Diaz, who dissented from the Mississippi Supreme Court’s ruling on the case, have also said that Byrom’s confession seems coerced, playing on a mother’s instinct to defend her offspring. “[D]on’t leave [Edward Byrom Jr.] hanging out here to bite the big bullet,” the local sheriff told Ms. Byrom during an interrogation. She replied: “I will take all the responsibility. I’ll do it.”

Meanwhile, Byrom’s current defense points to the fact that her son confessed four times to the crime, saying in one letter to his mom, “I did it.”

In a letter that the judge in the case knew about, but which was never shown to the jury, the son wrote: “Mom I’m gonna tell you right now who killed Dad ’cause I’m sick and tired of all the lies. I did, and it wasn’t for money, it wasn’t for all the abuse, it was because I can’t kill myself.”

Other things only cursorily introduced at trial – about mental illness and abuse as a child – have not been deemed significant enough by appellate courts to warrant a new trial. In 2006, the state Supreme Court, in a 5-to-3 decision, ruled that her defense’s performance in the trial “did not prejudice” her case.

Upholding Byrom’s conviction in 2013, the US Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit found that, though mistakes were made at trial, the original “trial court considered all of Byrom’s mitigating evidence and simply determined that it did not overcome the aggravating circumstances also deemed present.”

On Feb. 24, the US Supreme Court declined to hear the case, prompting Hood to move forward with plans for her execution.